The book that changed the world

On the Origin of Species, an instant bestseller, drew both applause and fury, writesTim Radford

![]()

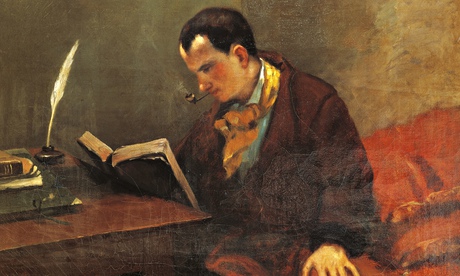

Darwin's bulldog: Thomas Huxley (1825-1895), English biologist and principal exponent of Darwinism (Photograph: Time Life Pictures/Getty Images)

Saturday 9 February 2008 00.06 GMT

Darwin's On the Origin of Species may have been a shock in 1859, but it was hardly a surprise: hundreds of naturalists, geologists and palaeontologists, many of them giants of science, must have known that something was coming, and some of them dreaded it.

Among the more alarmed readers were people like Charles Lyell and Adam Sedgwick, geologists who taught Darwin and who had done more than anyone to show that creation must have taken a lot longer than the Biblical seven days. Even more outraged was Richard Owen, the man who coined the word "dinosaur" and created the Natural History Museum in South Kensington, and whose theory of the origin of species was rooted in religion: he accepted some evolutionary adaptation, but from a set of archetypes created by God.

Much of the hostility and alarm came not overtly from religion, but from within science. The book was hailed, applauded, challenged, questioned, condemned, cruelly dismissed and, rather astonishingly, ignored: the president of the Geological Society of London in 1859 managed to give Darwin a medal of honour for his geological observations in the Andes and his stunning four-volume study on barnacles, without mentioning his seminal paper with Alfred Russel Wallace, or the forthcoming book.

Stiff competition

Origin was the book of the year - perhaps the book of the century - but it faced some stiff competition in 1859. Alfred Lord Tennyson printed the first Idylls of the King, his long cycle of Arthurian poems. John Stuart Mill wrote his mighty work On Liberty. Samuel Smiles delivered Self Help, a classic in a genre that has kept publishing houses alive ever since. George Eliot published Adam Bede and Charles Dickens produced A Tale of Two Cities.

It was the best of times and the worst of times for

Charles Darwin. The book attracted enormous attention, much of it admiring. A century and a half later, in a book called Darwin's Dangerous Idea, the philosopher Daniel Dennett called evolution by natural selection acting upon random mutation "the single best idea anyone has ever had", but the proposition of evolutionary change was not new, even in 1859.

The book appeared in a Christian world that was already aware - 50 years of debate and research by some of Darwin's critics had helped - that the Book of Genesis might not be taken literally. Lamarck, Wallace and Darwin all tackled the interesting question of why giraffes had long necks and the public took an interest. A popular song of 1861 sums it up:

A deer with a neck that was

longer by half

Than the rest of his family's

(try not to laugh)

By stretching

and stretching

became a Giraffe

Which nobody

can deny.

Darwin's version of the great giraffe argument made a splash, it made money - Darwin, says his biographer Janet Browne, was one of the first Victorians to negotiate what is now known as an advance against royalties - and it attracted interest far beyond the scientific community. Darwin received immediate support from that energetic churchman, naturalist and novelist Charles Kingsley, and later an admiring letter from Karl Marx.

Bestseller

Origin was a bestseller. The publisher John Murray ran off 1,250 copies and took orders for 1,500 even before the publication day, including 500 for a circulating library. A month later, he produced another 3,000 copies. Darwin helped sales along by a tactic now routinely employed by modern authors: he promoted it, says Browne, through "journals, newspapers, public lectures, controversial tracts and freethinking magazines".

Altogether, before the copyright expired in 1901, the publishers had printed 56,000 copies in the original format and another 48,000 in the cheap edition. This was not bad for a big fat volume that (apart from one diagram) failed the Alice in Wonderland test for a useful book: it had no pictures or conversations.

On the other hand, the storm it provoked alarmed Darwin. He had worried about its possible effect on his friends Thomas Henry Huxley and Charles Lyell. The first had scientific reservations, the second religious scruples. Lyell maintained his loyalty to Darwin, and Huxley became Darwin's most ferocious supporter. Darwin certainly needed his support.

One cruel review was published anonymously - by convention reviews were then unsigned - but the Darwin camp quickly identified the hand of Richard Owen, the titan of palaeontology. "Some of my relations say it cannot possibly be Owen's article, because the reviewer speaks so very highly of prof Owen. Poor, dear simple folk!" Darwin mused wryly afterwards, but he was hurt by attacks from scholars he had once respected.

'Old ladies of both sexes'

Origin was also famously attacked in print by Bishop "Soapy Sam" Wilberforce, again, anonymously. Huxley delivered an anonymous and highly favourable review in the Times and then defended Darwin against Wilberforce in the Westminster Review with some wonderful lines, including the classic jibe about the fears of "old ladies of both sexes" and that climactic and often quoted pronouncement: "Extinguished theologians lie about the cradle of every science as strangled snakes beside that of Heracles, and history records that wherever science and dogmatism have been fairly opposed, the latter has been forced to retire from the lists, bleeding and crushed, if not annihilated; scotched if not slain."

Reviews such as Huxley's turned the Origin into a book that everybody wanted to read. Darwin launched a revolution in biology but his epic study was just a beginning. His Voyage of the Beagle remains a delightful, astonishing book, whereas Origin has become one of the classics of science, and like most of the classics of science - think of Copernicus and Galileo, Newton's Principia and Linnaeus's Systema Naturae - more people know about it than have ever opened its pages.

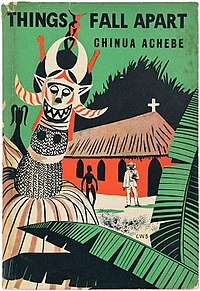

But Origin is part of the literary canon: Darwin joins Aristotle and St Augustine, Shakespeare, Milton and Stuart Mill, Dickens, Dostoevsky and Balzac in that pantheon of texts that provide the foundations of western culture. Origin meets the test of a great book: it mattered then, and it matters now. Its publication changed the world, and yet it can be read again and again, even in that changed world.

The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals

達爾文此書當然有翻譯

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals is a book by

Charles Darwin, published in 1872, concerning the biologically determined aspects of behaviour. It was published thirteen years after

On The Origin of Species and was, along with his 1871 book

The Descent of Man, Darwin's main consideration of

human origins, demonstrating the animal sources of human emotional life.

[edit]Development of the Book

While preparing the text of

The Variation of Animals and Plants under Domestication in 1866, Darwin decided to broaden his public statement of evolutionary biology with a book on human ancestry, sexual selection and secondary sexual characteristics including emotional expression. After his initial correspondence with the psychiatrist

James Crichton-Browne, Darwin set aside his material concerning emotional expression in order to complete

The Descent of Man which covered human ancestry and sexual selection. In 1871, Darwin started work on his newly independent book

The Expression of the Emotions, employing the unused material on emotional expression. In this way, Darwin brought his evolutionary theory into close approximation with

behavioural science, although many Darwin scholars have remarked on a kind of spectral

Lamarckism haunting the text of the

Emotions.

Darwin noted the universal nature of

expressions in the book: "...the young and the old of widely different races, both with man and animals, express the same state of mind by the same movements." This connection of

mental states to the neurological organization of

movement was central to Darwin's concept of emotion. In 1817,

James Parkinson (1755 - 1824) had described clinical and personal aspects of impoverished movement in his timeless medical classic

An Essay on the Shaking Palsy - which

Charcot later named

"Parkinson's Disease" - and Parkinson took only six weeks to write this treatise in stark contrast to the years he spent on his

Organic Remains of a Former World (1804 -1811), an illustrated account of his

fossil collection. Darwin himself showed many biographical links between

locomotion and his psychological life, taking long, solitary walks around Shrewsbury after his mother's death in 1817, in his seashore rambles with the Lamarckian evolutionist

Robert Edmond Grant in 1826/1827 and in the laying out of the sandwalk - his "thinking path" - at

Down House in 1846. These aspects of Darwin's personal development are discussed in

John Bowlby's (1990)

psychoanalytic biography of Darwin.

Darwin pointed to a shared human and animal

ancestry in sharp contrast to the arguments deployed in

Charles Bell's

Anatomy and Philosophy of Expression (1824) which claimed that there were divinely created human

muscles to express uniquely human

feelings. Bell's famous aphorism on the subject was: "expression is to the passions as

language is to thought". In the

Expression, Darwin reformulated the problem: "The force of language is much aided by the expressive movements of the face and body" - hinting at a neurological intimacy of language with psychomotor function. However, Darwin agreed with Bell's emphasis on the expressive functions of the muscles of

respiration. (This was an interesting opinion in view of

Bowlby's diagnostic conjecture that most of the symptoms of

Darwin's long term illness arose from an anxiety-related

hyperventilation syndrome). Darwin had listened to a remarkable attack on Bell's opinions delivered by the phrenologist

William A.F. Browne at the

Plinian Society in December 1826 when he was a medical student at Edinburgh University (see Walmsley's

Psychiatry in Descent, 1993). Nevertheless, Darwin explained later that he had been alerted to Bell's theory of expression in 1840, when he chanced on an edition of Bell's book during a visit to his wife's family in

Staffordshire. An important discussion of Darwin's response to Bell's neurological theories is provided by Lucy Hartley in her

Physiognomy and the Meaning of Expression in Nineteenth Century Culture (2001).

In the composition of the book, Darwin drew on world-wide responses to his

questionnaire (circulated in the early months of 1867) concerning emotional expression in different ethnic groups, on hundreds of photographs of

actors,

babies and

children, and on descriptions of

psychiatric patients in the West Riding Lunatic

Asylum at

Wakefield in West Yorkshire. Darwin carried out an unusually extensive and remarkable correspondence with

James Crichton-Browne, the superintendent of the Wakefield asylum. Crichton-Browne was the son of

William A.F. Browne and Darwin remarked to him that the book "should be called by Darwin

and Browne". He drew also on his personal experience of the symptoms of

bereavement, highlighting an autobiographical aspect to the book. Darwin considered other approaches to the study of emotions - including their depiction in the arts (exemplified by the actor Henry Siddons'

Practical Illustrations of Rhetorical Gesture and Action (1807)) - but abandoned them as unreliable sources of scientific information. (In 1833, Siddons' sister, Cecilia Siddons, married the phrenologist

George Combe).

![]()

Illustration of grief from

The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals[edit]Structure of the Book

Darwin opens the book with three rather uncomfortable chapters on "the general principles of expression", followed by a section (three chapters) on modes of emotional expression peculiar to particular species, including man. Then, he moves on to the main argument with his characteristic approach of astonishingly widespread and detailed observations. Chapter 7 discusses "low spirits", including

anxiety,

grief, dejection and

despair; and the contrasting Chapter 8 "high spirits" with joy, love, tender feelings and

devotion. Subsequent chapters include considerations of "reflection and meditation" (associated with "ill-temper", sulkiness and determination), Chapter 10 on hatred and

anger, Chapter 11 on "disdain, contempt,

disgust,

guilt,

pride, helplessness,

patience and affirmation" and Chapter 12 on "

surprise, astonishment,

fear and

horror". In Chapter 13, Darwin discussses complex emotional states including self-attention,

shame,

shyness,

modesty and

blushing. Throughout these chapters, Darwin's concern was to show how human expressions link human movements with emotional states, and are genetically determined and derive from purposeful animal actions. Darwin concluded work on the book with a sense of

relief. The attacks on his work by the Roman Catholic biologist

St George Mivart in 1871/1872 had coincided with a severe aggravation of Darwin's illness, with mysterious symptoms (including

vomiting,

sweating,

sighing,

weeping and

shivering); but the intervention of

Thomas Henry Huxley with a savage review of Mivart's

Genesis of Species (1871) and Darwin's continuing correspondence with

James Crichton-Browne (amounting to more than forty letters with many enclosures) seemed to encourage a resolution of his symptoms as he brought this important work on

emotional expression to a conclusion. In the last decade of his life (1873-1882), Darwin's health was generally much improved. The complex interaction of Darwin's symptoms with his scientific theories and his personal and family relationships remains a considerable puzzle.

[edit]Cultural Relations of the Book

The proofs, tackled by his daughter

Henrietta ("Ettie") and son

Leo, required a major revision which made Darwin "sick of the subject and myself, and the world". It was to be one of the first books with photographs, with seven heliotype plates, and the publisher

John Murray warned that this "would poke a terrible hole in the profits". The published book displayed an extraordinary assembly of illustrations - almost in the manner of a Victorian family album - with engravings of the Darwin family's domestic pets, portraits by the faintly disreputable Swedish photographer

Oscar Rejlander (1813-1875) ("of Victoria Street, London"), and illustrational quotations from the

Mecanisme de la Physionomie Humaine - Analyse Electro-Physiologique de L'Expression des Passions (1862) by the eminent French neurologist

Duchenne de Boulogne (1806-1875). Darwin was careful to ensure Duchenne's agreement to his association with the project and the two men had a brief correspondence. Duchenne's involvement brought a dramatic and psychological dimension to Darwin's book - he had been a powerful influence on

Jean-Martin Charcot. Indeed, Charcot often referred to Duchenne as "

mon maitre" ("my teacher") and sat with Duchenne on his deathbed. Duchenne's complicated classic introduced a number of novel neurological themes, including photographic illustrations as well as his technique of the electrical stimulation of nervous structures - in this case, the seventh cranial (facial) nerve. On 8th June 1869, Darwin sent his copy of Duchenne's book to Crichton-Browne, seeking his opinion. Crichton-Browne seems to have mislaid the book in his asylum for almost a year, causing Darwin some anxiety. Two years later, Crichton-Browne invited

David Ferrier to conduct experiments on the electrical stimulation of the motor centres in the brain.

The lavish style of scientific illustration (see Phillip Prodger's

Darwin's Camera) was followed in work on

animal locomotion (

co-ordinated movement) by Eadweard

Muybridge (1830-1904) and

James Bell Pettigrew (1832-1908); and, also, in

D'Arcy Thompson's masterpiece

On Growth and Form (1917). Darwin himself, inveterately original, moved from animal locomotion (and emotional life) to the questions of insectiverous plants and

The Power of Movement in Plants in his book of that title in 1880. As the torch of anti-Darwinism passed from theologians to social scientists, Darwin's biological interpretation of the emotions was to prove something of a dead-end for a century or so. Anthropologists like

Margaret Mead emphasised the cultural determinants of emotional expression, and argued that expression varied fundamentally from one culture to another. However, empirical research by

Paul Ekman and others has shown this view to be misconceived. Since around 1970, in an atmosphere newly receptive to biological approaches to human behaviour, it has become clear that there were many distinguished scientific contributions in line with Darwin's ideas. These include

William James'

What Is An Emotion ? (1884),

Walter Cannon's

Bodily Changes in Pain, Hunger, Fear and Rage (1915) and Schachter and Singer's (1962) studies on the interaction of social, psychological and physical factors in the generation of emotional states.

Thorstein Veblen's sociological classic

The Theory of the Leisure Class (1899) assumed an evolutionary perspective and advanced a persuasive narrative concerning the elaboration of gesture and posture into a culturally encoded system of decorum and good manners. In 2003, the New York Academy of Sciences published

Emotions Inside Out: 130 Years after Darwin's The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals, a Compendium of 37 papers with current research on the subject.

It is noteworthy that

Freud's early publications on the symptoms of

hysteria acknowledged a debt to Darwin's work on emotional expression, that Freud's later

Interpretation of Dreams (1900), a work which lingered on the visual presentation of mental processes, contained no illustrations and that Darwin published nothing on

dreams as a mode of emotional expression.

The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals proved to be very popular, perhaps surprisingly, with a Victorian readership more accustomed to hearing about the virtues of

self-control (inhibition) rather than the value of self-expression. Today, the book can be viewed as a pioneering work in the burgeoning field of

behavioural genetics. Some critics have regarded Darwin's sketches of animal behaviour as

anthropomorphic, and the whole book as curiously Lamarckian in character. It quickly sold over 9000 copies and was widely praised as a charming and accessible introduction to Darwin's theories.

A second edition was published by Darwin's son around 1889. It did not contain several revisions wanted by Darwin, which were not published until the third edition of 1999 (edited by

Paul Ekman).

[1][edit]See also

[edit]Notes and references

[edit]External links

- Freeman, R. B. (1977), The Works of Charles Darwin: An Annotated Bibliographical Handlist (2nd ed.), Folkstone: Dawson, http://darwin-online.org.uk/EditorialIntroductions/Freeman_TheExpressionoftheEmotions.html.

- Darwin, Charles (1872), The expression of the emotions in man and animals, London: John Murray, http://darwin-online.org.uk/content/frameset?itemID=F1142&viewtype=text&pageseq=1.

- Ekman, Paul (editor) (2003), Emotions Inside Out: 130 Years after Darwin's The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals (1st ed.), New York: New York Academy of Sciences, http://www.nyas.org/Publications/Annals/Detail.aspx?cid=f003767c-5c61-4597-abdc-02d159294a0c.

Free e-book versions available on the internet:

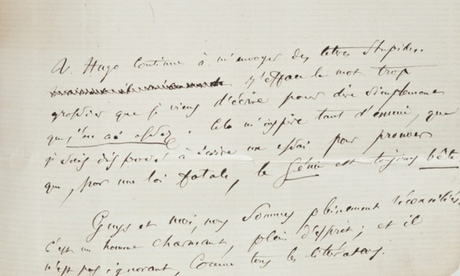

Detail from Baudelaire's letter, containing his private opinion of the 'stupid' Les Misérables author. Photograph: Christie's

Detail from Baudelaire's letter, containing his private opinion of the 'stupid' Les Misérables author. Photograph: Christie's The first edition of Les Fleurs du Mal, tooled in gold and silver, colored inlays of flowers and symbols of death and evil, similiarly tooled. Photograph: Christie's

The first edition of Les Fleurs du Mal, tooled in gold and silver, colored inlays of flowers and symbols of death and evil, similiarly tooled. Photograph: Christie's

![「 Les funérailles de Victor Hugo, la foule place de l'Etoile (1er juin 1885) Jean Béraud 1885 @[159737906547:274:Musée Carnavalet - Histoire de Paris] 」](http://fbcdn-sphotos-b-a.akamaihd.net/hphotos-ak-xpf1/v/t1.0-9/p240x240/19493_842775475808930_7923198242478759601_n.jpg?oh=4b146d8542c6245c5d521c31fe2d32c4&oe=55FA6D11&__gda__=1443493941_13468257f1a0c00ce90187b0320ce96a)

Darwin's bulldog: Thomas Huxley (1825-1895), English biologist and principal exponent of Darwinism (Photograph: Time Life Pictures/Getty Images)

Darwin's bulldog: Thomas Huxley (1825-1895), English biologist and principal exponent of Darwinism (Photograph: Time Life Pictures/Getty Images)