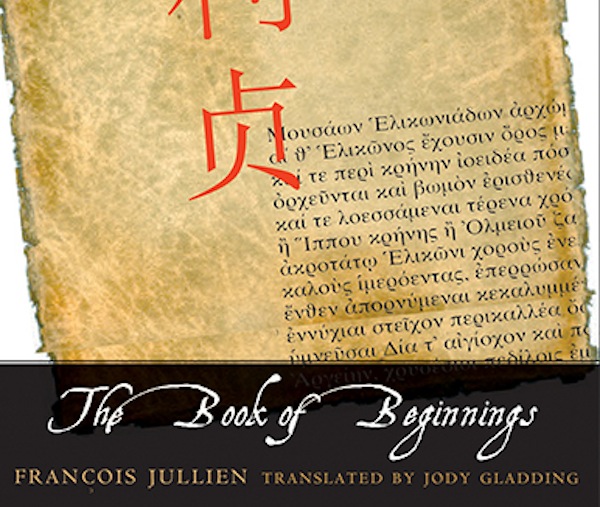

這本回憶錄

My German Question: Growing Up in Nazi Berlin By Peter Gay,我從末章讀起,還算很有內容的。

"Even before the events of 1938-39, culminating in Kristallnacht, the family was convinced that they must leave the country. Gay describes the bravery and ingenuity of his father in working out the agonizing emigration process, the courage of the non-Jewish friends who helped his family during their last bitter months in Germany, and the family's mounting panic as they witnessed the indifference of other countries to their plight and that of others like themselves. Gay's account - marked by candor, modesty, and insight - adds an important and curiously neglected perspective to the history of German Jewry."--BOOK JACKET.CHAPTER ONEMy German QuestionGrowing Up in Nazi Berlin

By PETER GAYYale University PressReturn of the Native

On June 27, 1961, we crossed the Rhine Bridge from Strasbourg to Kehl, and I was subjected to the most disconcerting anti-Semitic display I had endured since I left Germany twenty-two years earlier. After a delightful few weeks touring in France, my wife, Ruth, and I were on our way to Berlin. A colleague in Columbia's German department, Henry Hatfield, was giving a course on Thomas Mann at the Free University in West Berlin and had invited us to hear him lecture. Touring through France had been an unmitigated delight. We moved westward at a stately pace through the chateau country all the way to Angers, with its magnificent tapestries, eating and drinking our way across the region. Then we turned south to take in cities like Bordeaux, getting slightly drunk at a degustation at Chateau d'Yquem on the sweet local dessert wine, sleeping in double beds guarded by crucifixes overhead. In contrast, our prospects for a German stay seemed far from inviting.

The Free University, its very name a calculated provocation to its East Berlin ancestor, was an institution born or, rather, assembled faculty by faculty, department by department, not long after the war. From 1948 on, academics from the old University of Berlin began to set up new headquarters in idyllic Dahlem. (The old university was renamed Humboldt University by East Germany's Stalinist masters to exploit the great prestige enjoyed by Wilhelm von Humboldt, the humanist who more than anyone had been responsible for the founding of the university in 1810--and who, no doubt, would have been among the first to be arrested in the communist regime.) Dahlem, a district of broad avenues and once magnificent villas, had been spared the worst of Allied bombings, but like all of Berlin it showed the blemishes left by the war. Its avenues were still largely intact, but the villas had been turned into discreet boarding houses and small hotels. This had been a Berlin out of my family's reach, but its famous Grunewald, a sizable, carefully cultivated forest, was familiar to me: as a boy, I had ridden my bicycle in its designated paths.

The academic experiment in Dahlem was a symptom of the deep clefts that polarized the shattered city; in the Soviet sector, covering the eastern half of the city, Russian tanks and troops, Russian propaganda, and servile German lieutenants had created a totalitarian atmosphere. And their ideology necessarily pervaded the University of Berlin, which the country's rulers turned, most drastically in the social sciences and the humanities, into a haven for conformism and a seedbed of their party line. There was great uneasiness in the western zones of the city, a fear (far from paranoid) that the East Germans, willing puppets of their Soviet masters, might one day invade their neighbor. In fact, only two weeks after our short stay the Stalinist state, called, with a nice sense of the magic of names, the German Democratic Republic, threw up the infamous Wall that dramatized the division and, it then seemed, made it permanent.

The irony of a visit to the Free University was not lost on me. More than a decade earlier, the place had been the cause of a memorable little dispute--memorable at least to me. Around 1950, Franz Neumann, a senior colleague in my department at Columbia, announced that he was on his way to Berlin to do some work for the Free University. As I did in my lowly post as instructor (our elders in the rather grandly named Department of Public Law and Government kept the junior faculty humble lest we begin to nourish the fantasy that someday there might be a tenured post for us), only on a far more exalted level, Neumann taught a course on the history of political thought. Among graduate students and the junior faculty he was a highly respected presence: immensely knowledgeable, commanding a bibliographic range that impressed all his devotees, and benevolently interested in those just entering their professional careers. He made a striking figure: compact, with an eagle's nose, hooded eyes, and a bald head, he looked quite like an idealized Roman emperor. That he needed to wear a hearing aid only seemed to increase his distance from us, but we soon learned that the reserve we perceived was a product of our awe.

In his native Germany, Neumann had been an outspoken trade union lawyer. In May 1933, he barely escaped arrest when a friend who had landed a job with the new regime warned him that he had better leave, the sooner the better. The next morning, he took a plane to London, bringing with him his Marxist Hegelianism, his intimate ties to the Frankfurt School, and his close friend Herbert Marcuse. His bulky study of the Nazi system,Behemoth, written after he had moved to Columbia, was then an important text and cemented his reputation among his enthusiastic following. And now this active, consistent anti-Nazi was volunteering to set foot on German soil!

Like my contemporaries at Columbia, I found this hard to fathom. True, Neumann had gathered some notoriety among us with his inflammatory assertion that the Germans were the least anti-Semitic people in Europe. This sally, of which I have often thought since, irritated me, but I was disposed to write it off as a provocation designed to shake us out of our complacent and categorical judgments. To assist in the rehabilitation of the Enemy of Civilization, though, was something else. Filled with righteous indignation, I confronted Neumann at the Columbia Faculty Club: "How can you be so sentimental?" His response: "How can you be so sentimental?"

It was an inelegant riposte, especially for one so quick-witted as Neumann. But its very lack of originality was like a line drawn in the sand, as if to say, You have your position and I have mine, and there is no way we can reach a compromise, no point in discussing it further. Here were two intelligent academics dangerously near a quarrel, both men of goodwill, both German-born, both emigres who had had a close call. We let it drop, though I did not stop thinking about the incident.

I did not realize it then, but the episode was evidence that there was no "correct" attitude to take toward the Germans. Individual experiences and private emotions, not all of them directly related to life under the Nazis, justified whatever attitude we took. Some refugees would not buy German cars or appliances, eat in German restaurants, sleep in German hotels, or even concede that the country had ever had a worthwhile culture; a few of them even declined to accept financial restitution offered by the German government from the early 1950s on. I belonged to this camp for some years; I would not even read German, a vengeful stance from which I was obliged to retreat once I entered graduate school in 1946. Many other German Jews who had suffered just as much under the Nazis had no such qualms. My father was of this second party; I remember his Burkean comment--he had never read a word of Burke--that one cannot properly condemn a whole nation. It still rings in my ears. This was the attitude I would slowly, reluctantly, and never completely make my own. Neumann's taunt pursued me: "How can you be so sentimental?"

In 1961 the lesson had not yet quite sunk in. I had left Germany in 1939 as Peter Joachim Israel Frohlich (the "Israel" courtesy of the Nazis); I returned as Peter Jack Gay, proud American citizen since 1946. It was a beneficent transformation that I virtually sensed in my bones, as if my American passport made me feel a little taller. The depressing sense of total vulnerability before implacable Nazi officialdom had given way to a certain feeling of power. When my parents and I emigrated, we were literally fleeing for our lives; now I could stay in Germany as long as it pleased me or, if something rubbed me the wrong way, leave without having to pay ransom or endure the chicanery at which the Nazis had proved so inventive. Now I walked on the Wilhelmstrasse, once the center of government, a street on which in 1938 I had been forbidden to set foot.

But the moment our rented Dauphine touched German soil on the Rhine Bridge, I regretted my complicity in this adventure, an invitation too casually offered and too hastily accepted. I could have listened to Henry Hatfield's lectures just as easily in New York--in fact, more easily. Apparently my American self-confidence was not solid enough to let me relax among Germans or look forward to seeing the houses where I had spent my earliest years, the parks where I had played, the schools where I had recited, the stadiums where I had cheered. I had returned to Europe three times before: in 1950, when I spent some six agreeable and productive weeks in Amsterdam doing research on my dissertation, and in 1955 and 1958, to visit archives and friends in England and travel in France and Italy with friends. Each time, I had refused to enter Germany, near though it was.

After that incident at Kehl, I wished I had listened to my anxiety and my antagonism. Getting out of the car on the German side to buy marks for dollars in a little kiosk, I had faced a young woman clerk behind a grille ready to serve me. She had looked at me coldly, her eyes registering pure hatred as I handed her my passport. A glance at her had left no doubt in my mind: murderous anti-Semitism was alive and flourishing in my native land.

What had happened? Nothing. The clerk dealt with me as she dealt with everyone: correctly and impersonally. If there really was any expression in her eyes, it was surely boredom. I did not know the word projection then, nor would it have helped me to thaw out antagonisms so long frozen in my mind. Not even my affectionate travel companion, wrestling with her own feelings, could give me ease. The fact was that this clerk did not hate me; she barely registered my existence. I hated her.

Of course I was freer to hate her than I would have been in the 1930s. As we proceeded on our way, there seemed to be so much, so many, to hate. In 1961 I was thirty-eight, so that the Germans my age had been adolescents under the Nazis, most of the boys enrolled in the Hitler Jugend, most of the girls in the Bund Deutscher Madchen. Those only a little older than I had been adults. Many of them had screamed for Hitler and voted for him, applauded the Nazis' acts of persecution, perhaps cheerfully participated in their killings; many of them had profited from the legalized thievery that had handed over Jewish-owned businesses, Jewish-owned houses, Jewish-owned art collections to "deserving Aryans," had driven musicians, artists, lawyers, physicians, once their fellow citizens, first into isolation and then into exile--always provided that their victims could manage (as we called it) to "get out." Wherever we went, there were Germans: driving their cars, walking their dogs, lounging in cafes, waiting on customers. And they were all speaking German as though nothing had happened, as though their very language had not been permanently contaminated in the Thousand Year Reich.

Their overwhelming presence should not have astonished me: who should surround me in Germany but Germans? And what should they be speaking but German? But such sensible questions were not available to me--not yet. I was at an unstable midpoint along a winding road toward answering my German question, a question that I have not yet completely put to rest and probably never will. Since that first foray in the midsummer of 1961, I have been to Germany many times and for extended visits, made good friends there, done extensive research in libraries and archives, attended conferences, lectured to historians and psychoanalysts and, at the Frankfurt Book Fair, to publishers. Yet even today, when I hear German spoken in an American restaurant or airport, I cannot suppress a slight tensing up and the question, What are they doing here?

Well, I took my German currency from the clerk, climbed back into our Dauphine, and proceeded toward Berlin. A brief stopover in Gottingen to visit a colleague then on leave in Germany only raised the level of tension and fed my paranoia. Rather tactlessly, our host proposed lunch in a large local beer hall, which turned out to be crowded to the walls with elderly fraternity men, many of them wearing their traditional gear. That was bad enough, but when they took to singing their old student drinking songs, Ruth and I had had enough and left. It was poor preparation for the ordeal to come: Berlin was waiting in the distance.

For Ruth and me, four or five uncomfortable days followed. We did not get on with each other, whether in the car or our hotel room; at one point we even discussed turning back. We snapped at each other, bickered in unaccustomed ways. We had had words before and would have words again, but never for a reason so obviously imposed from the outside. It is pointless to assign blame: the provocation of Germany all around us was simply too strong, for Ruth as a newcomer, American-born but from a Jewish Eastern European family, as much as for me, the returning native. Contemporary history raw and ugly had caught up with us.

Worst of all, Berlin proved a letdown. Of course, the city was no longer what it had been in the 1920s and 1930s, when I was a growing boy. The Nazis and Allied bombers had taken care of that. It was not so much that the scars of war, which had ended sixteen years before, were still all too visible. The stalwart working-class women, the memorable Trummerfrauen, who drudged to rehabilitate the city literally stone by stone, had elicited widespread admiration, including mine. But their tireless work had not been enough; there were simply too many wrecks to salvage. After seeing photographs of Berlin in the spring of 1945, a once splendid capital now looking like a gap-toothed derelict, I had expected little else. It was not the physical Berlin of 1961 that further dampened my already exasperated spirits, it was my experience of walking through the city. Mindful of Marcel, the protagonist of Proust's great river of a novel, I had anticipated a flood of memories, as though my old neighborhoods would be so many madeleines. But if for him a madeleine dipped in linden tea opened up the world of a long-forgotten past, there were no madeleines for me.

Perhaps nothing illustrates my emotional numbness better than this failure. It reminded me of my inability to weep at my father's death in January 1955. I worked on luring memories from their hiding places, hoping that feelings would wash over me at the dramatic moments I tried to conjure up. Inevitably, it was in walking through the streets where I had spent my childhood that my emotions--and my frustration at my lack of emotions--were most intense. For the first thirteen years of my life, my parents and I lived in one or the other of two apartment houses on the Schweidnitzerstrasse, a street in Halensee. The district, at the western edge of the borough of Wilmersdorf, itself in the western part of Berlin, housed middle-income and lower-middle-income bourgeois only a couple of miles and many thousands of marks from a borough for the gentry like Dahlem.

Schweidnitzerstrasse was unusual in one respect: it was one block long, with some fifteen apartment houses and a small factory. I had played marbles and ball on that street with my contemporaries, for it had little traffic--no buses, no street cars, few automobiles. Right down to the 1930s, few in the middle middle class had cars; my father did have one, an Opel, used largely for business purposes. There was a pub at one corner and a laundry with a huge mangle that greatly impressed me when I was little. For groceries and household items one turned the corner to the Westfalische Strasse. There was one store not far from us, dark, dank, smelly, that sold only potatoes, with a bewildering array of varieties, each in its bin.

Apart from its lilliputian size, our street was of a variety common in the Berlin of my childhood, largely built up before the First World War: its apartment houses were attached side by side, each five stories tall and decorated with an ornate facade; the center segment from the second to the fourth floor jutted forward, giving the living room some added light. A few had balconies that almost destroyed the harmony of the street picture. Almost, but not quite: the restlessness of each building was neutralized by the identical restlessness of its neighbors. Thus Schweidnitzerstrasse made its unpretentious contribution to Berlin's characteristic style, which I liked so much that I believed it must be the natural face of any city.

Like the houses in most other residential districts, those in the Schweidnitzerstrasse were joined at the corners, forming a hollow square in the center, with a spot of grass, on occasion a pitiful misshapen tree, giving the hollow some green, a welcome change from the gray of the stone. During the Depression, out-of-work amateur singers would stand there, addressing the windows in hope of garnering a few pennies. One of their songs, which I must have heard often enough around 1930, was short and doleful, and I can reproduce its melody as well as its text:

Arbeitslosigkeit, Arbeitslosigkeit,

Oh, wie bringst du uns so weit!

Meinen Vater kenn ich nich',

Meine Mutter liebt mich nich',

Und sterben mag ich nich', bin noch so jung--

"Unemployment," it went, "unemployment, Oh, how far you have brought us. My father I don't know, my mother doesn't love me, and I don't want to die: I'm still so young."

Now, in 1961, I set up situations that might encourage me to take possession of the life I had once led. But I was checked again and again as I strolled--often alone--through my old streets, past my primary school and myGymnasium. I hunted for landmarks in the neighborhood in which I had grown up. I walked through a park, the Hochmeisterplatz, a two-minute stroll from my first street, to a large, fenced-in playground where at five I had been king of the sandbox and at eight had ridden my bicycle. Across the street from that playground there was a Lutheran church in the Wilhelminian neo-Gothic design, boasting a faceted slender spire and built in the all too familiar dark red brick--not a touch of the pink tinge that can make brick so attractive--which dated the building to the late nineteenth century.

My past, then, was proving to be a mosaic with central pieces missing. I had not reckoned with the fact that one does not arrange for the magic of the madeleine; it comes uncalled or not at all, where and when and how it lists. I discovered in these dismal few days that the images and aroma that rose for Marcel from his cup of linden tea with all the perfume of lost years cannot be forced or prompted. In short, I found that making my way through familiar quarters and looking at familiar buildings produced only a few anemic fragments from my childhood.

Significantly, three of these were horrifying and had frightened me when I was a boy: an idiot who wandered the streets of northern Berlin near my Onkel Siegfried's apartment house, a stunted creature with a gigantic head, awkward gait, and slavering mouth; the torso of a headless chicken that twitched and moved as though it were still alive; the photograph in a magazine of a German soldier dreadfully wounded in the First World War but still living even though half of his face had been shot away. Pleasant memories were much harder to come by.

Candor obliges me to record one episode on this return trip, though, that I experienced as downright bracing. We were driving through Berlin--I was at the wheel--when a policeman waved me over. I had gone through a red light, something I am not in the habit of doing--a tribute to my preoccupation. He asked for my papers, and I handed him my driver's license and passport. As he perused it, he evidently noticed that I had been born in Berlin. He handed back my documents and, in a reasonable, almost paternal tone, suggested that I drive more carefully in the future. My first brush with German authority generated no echoes of the 1930s.

Actually, I felt compelled to acknowledge that the Berlin of 1961 was showing a great deal of animation. Those who had seen it near death, just after the surrender in May 1945, were amazed to see how far the city had come. Its academic institutions were reaching out to universities abroad; the invitation to an American like Henry Hatfield to lecture on so problematic a German writer as Thomas Mann was a token of recovering health. After all, Mann was controversial as an exile who had been unsparing in condemning his homeland, and it was good not to repress but to discuss his meaning for his fellow Germans. We went to hear Hatfield in a large, brand new auditorium and enjoyed it as much as did the students, who drummed their fists on the tables before them as a token of animated approval.

Physically, too, Berlin was working effectively toward a measure of normalcy. Most of the postwar architecture was emergency construction, almost aggressively indifferent to aesthetic considerations, monotonous, listless--utilitarian, in the worst sense of the word. In general, then, post-1945 building in the city, private as much as public, looked like a joyless, unsuccessful facelift, a painted smile. Only a handful of the new buildings were beginning to break with this dreariness. And at least one of the architectural casualties of the war had been turned into an imaginative memorial. Or was it? Such doubts served to undermine my few conciliatory sentiments. High on my list of what I needed to see was the ruin of the Kaiser-Wilhelm-Gedachtniskirche, a grandiose neo-Gothic Protestant church that Germany's last emperor, the flamboyant Wilhelm II, had had built in the early 1890s to commemorate his beloved grandfather Kaiser Wilhelm I. It stood conspicuously in the center of Berlin's western shopping district, at the eastern end of the Kurfurstendamm. This confection, overloaded with heavily tinted glass and servile mosaics celebrating Germany's emperors, had been severely damaged in an Allied air raid, and the city fathers had decided to shore up what was left and, to emphasize its fragmentary remains, place two aggressively modernist constructions next to it.

The torso was a reminder, but in my sour mood I asked myself, a reminder of what? A furious reproach to the Allies for bombing the city so heavily? This cynicism could arise in me at any moment without warning, and that helped to make my first return to Berlin so dismaying. Could it not be, after all, a bitter reproach to the Nazi regime for what it had done to Germans and to Germany? Surely nothing could be a more persuasive indictment of Hitler and his gang than this brooding ruin. Before Germany plunged the world into war in September 1939, every new section opened on the Autobahn, every new stadium or post office constructed in a small town, was credited to Hitler alone: Das verdanken wir unserm Fuhrer, read the ubiquitous posters--"We owe this to our leader." But the death and devastation, the famine and humiliation that the war visited on the home front, they too were owed to their Fuhrer--auch das verdanken wir unserm Fuhrer--and I could not help but think this a salutary memento.

If these ruminations, these sudden shifts in mood, sound inconsistent, they were; my first return to Berlin was an endless attempt to resolve conflicting responses. Yet when all is said, Berlin's display of energy did have its gratifying side for me; I discovered in myself traces of the Berliner I had been before 1933, traces I thought I had forever banished. I recalled more than once that defiant old slogan Berlin bleibt doch Berlin--Whatever happens, Berlin remains Berlin--and it had a bracing appeal for me, until it was swamped by my silent hatred.

Unlike other great metropolitan centers, unlike Paris or London, Berlin had been a parvenu among capitals. A small, slowly growing garrison city, headquarters for the impoverished but assertive Hohenzollern dynasty, it had expanded exponentially in the nineteenth century and started to acquire representative cultural institutions: museums, concert halls, opera houses. Late in the nineteenth century there had been a bootless competition between Munich and Berlin as to which was more modern, more civilized; around 1900, it seemed as though Berlin was winning this culture war.

Berlin had long been much despised, which is to say much envied, by other cities. Its humor, blunt, cynical, democratic, busy deflating the bloated and the pretentious, was proverbial. It demystified political rhetoric no less than excessive advertising claims. I remember a slogan used to sell a fire extinguisher that was prominent in my childhood years: Feuer breitet sich nicht aus, Hast Du Minimax im Haus--Fire won't spread if you have Minimax at home--which some Berlin wit had undermined with the irreverent commentary Minimax ist grosser Mist, Wenn Du nicht zuhause bist--Minimax is a lot of junk when you're not at home. Goethe, who visited Berlin only once, found the "wit and irony" of its denizens quite remarkable; with such an "audacious human type" he decided that delicacy would not get very far and that one needed "hair on one's teeth"--Haare auf den Zahnen--a rather baffling tribute that became proverbial because it seemed somehow just right.

Berlin's characteristic speech was quite antiauthoritarian; deflating in its harsh and terse accents, it came naturally to working-class Berliners and was affected by sophisticates who thought linguistic slumming chic. When the operetta composer Paul Lincke extolled Berlin's inimitable air, the Berliner Luft, he did not have meteorology in mind but an incontestable mental alertness. And those who agreed with Lincke sensed that he was only putting to music what everyone already knew. Berlin was the kind of city on which travel writers and visiting journalists inevitably bestowed the epithet "vibrant."

This vitality drew heavily on its diverse population, doubtless one reason why Jews felt so much at home there. In 1933, more than 150,000 of them, some 30 percent of the Jews in Germany, lived there. It was a common saying that every Berliner is from Breslau, obviously hyperbole, though it happened to fit my mother, who was born in Breslau and moved to Berlin after her marriage in 1922. In the 1880s Theodor Fontane, poet, historian, critic, novelist, the most interesting German writer between Goethe and Mann, observed that what made Berlin great was its ethnic mix: the offspring of the Huguenots, the provincials who streamed into the city from the surrounding province of Brandenburg, and the Jews. One of these ingredients, the Jews, was sadly absent in 1961. Four years later, when the New School for Social Research in New York honored the social scientists who had fled Hitler's Germany to the United States, Willy Brandt, mayor of West Berlin and an influential politician in the Social Democratic Party, received an honorary degree. And in a moving address--I heard it--he pleaded with his listeners to acquit the youth of Germany, which was, after all, innocent of their parents' crimes, and exclaimed, with the blunt honesty that was his signature: "We miss our Jews."

He had every reason to miss us though I doubted that his regrets were of vital concern to most Germans. A sizeable segment among Berlin's Jews had helped to shape its culture, far out of proportion to their number, as scientist, historians, poets, musicians, editors, critics, lawyers, physicians, art dealers, munificent collectors, and donors to museums. Brandt's exclamation of 1965 confirmed the impression I had gathered four years earlier: Berlin's bourgeois culture had lost one of its mainstays and had not replaced it.

It was only to be expected that the Nazis found Berlin a hard nut to crack, even when Goebbels was put in charge of winning it over to the "movement". The city's culture had contributed impressively to what was anathema to the Nazis and their supporters: modernist experimentation with its unconventional theatres, avant-garde novelists and publishers, adventurous newspapers and critics. Their reputation to the contrary, Berlin's Jews were by no means all cultural radicals; many of them, in fact, were solid conservatives in their tastes. Nor were they conspicuous in the city's widely advertised vice. Naturally, I was far too young to partake of the city's forbidden fruit and knew virtually nothing about it. But I early had a taste of its movie palaces, its variety theatres, its sports stadiums, and its bustling streets.

One got around Berlin via an efficient system of subways, elevated trains, and buses, to say nothing of streetcars--we called them die Elektrische. I can still hear the screeching noise the cars made, especially around curves, the bright bell the conductor rang warning pedestrians to get out of the way, and the hissing sound that came, occasionally accompanied by little sparks, as the movable rods fixed on the roof of the car made contact with the power line strung overhead. The modern buses that were the streetcars' main competitors were another source of pleasure to me, especially the double-deckers. I found it almost obligatory to climb upstairs and observe the city scene passing beneath me. And nothing could be more thrilling, even a little frightening, than to be on the bus--naturally on the upper deck--as, swaying slightly, it slowly passed through the center space of the Brandenburg Gate; it always looked as though it would scrape against the columns on either side, and it always got through unscathed.

Thus, even though Berlin covered an immense terrain, it seemed very accessible, a fine city for walking. It had made its vastness official in 1920, three years before I was born, by incorporating its proliferating suburbs. But this grab for territory had done no damage to the city's splendid shopping avenues, refreshing parks with comfortable benches, streets with their ever changing incidents, carts from which secondhand dealers sold books. For a walker in Berlin, the favorite west-east artery was the world-famous Kurfurstendamm, with its marvelous wide sidewalks. More than two miles long, it started rather unpretentiously near the street where I lived, but as one walked eastward, one could browse in bookstores, window-shop for clothing, china, even fancy automobiles, and pass movie palaces like the Alhambra (another casualty of the war), to which my parents had taken me, and the Universum, a masterpiece by the brilliant romantic modernist architect Erich Mendelsohn--another emigrant after 1933. Perhaps best of all were the outdoor cafes, where one could sit at leisure, spooning up cake with whipped cream and watching the parade of Berliners on their way. Even before I was ten, I could recognize Berlin's special ambience.

One reason for Berlin's size was that it had been built on a swamp. This meant, until more advanced building techniques unfortunately made skyscrapers practicable, that its profile was low, permitting an expansive canopy of sky overhead. True, it was often gray, but one got used to that. There were a handful of startling exceptions that only underscored the horizontality of Berlin: the skeletal Funkturm, a poor cousin to Paris's Eiffel Tower, dating from the mid-1920s; an office tower for the Borsig locomotive works; and the most dramatic, most uncompromisingly modern building, the ten-story Shell House facing one of the city's canals. With its curved facade and emphatic bands of windows, it was something of a sensation in my childhood. When I saw it again in 1961, it was dilapidated but still standing, a mocking comment on past glories.

All these vistas were secondary to Schweidnitzerstrasse. The apartment in which I spent my early childhood was in No. 10, and even without any concrete memories, I can still sense its roominess and comfort. It even boasted a Rauchzimmer--a smoking room--an extra living room that hinted broadly at affluence: the gentlemen retreating to puff on their cigars while the ladies stayed behind to talk of household matters or children and to gossip about unlucky absent ones. For my family, this was largely academic: we entertained rarely, and the smoking room was, I think, never used for its designated purpose. At all events, in the depths of the Depression we moved to far more modest quarters across the street in No. 5. That must have been in 1930.

Our new apartment was acceptable, but only just, a categorical statement that we had come down in the world. We were not exactly poor. We traveled a little, we had money for tickets to soccer games and an occasional movie. Our new apartment had a room for a lodger, with whom, I think, I never spoke (I do recall his name--Bethke--another instance of the caprices of memory), and for a live-in servant, Johanna Hantel. I had a room of my own, a tiny cubicle outfitted with a folding "desk"--really a board covered with linoleum--under my window.

For their part, my parents, without ever complaining, made do with an ingenious arrangement: they turned the largest room into two: a living-dining room, which had a window overlooking the courtyard, and a bedroom for the windowless half. To secure at least a modicum of privacy, they enlisted our two most massive pieces of furniture, a blond moderne armoire placed back-to-back with an ornate buffet, the two acting as a divider. That buffet, a looming mahogany affair with glassed-in turrets at the top sitting on a bulky bottom section with three doors, was to play a certain role in my life.

To relieve some of this drabness, my parents put up several pleasing watercolors of farmyards and half-timbered barns by Josef Menzel--not the celebrated artist Adolph Menzel, but a painter who made a living decorating expensive china plates and cups with well-observed rustic scenes. I have them now. A valuable two-foot-tall porcelain parrot, mainly in brilliant white with yellow and green feathers, which did not survive our emigration, was a reminder of my father's profession--he represented major glass and porcelain manufacturers--and a handsome sight to see. I contributed a bit of color to our apartment with my parakeet, Purzel, a colloquialism for "little fellow," a blue little bird as impudent as they come. It liked to take its food from my lips and interfered with our card games by picking up cards from the table. With its curved beak, I told myself ruefully, it even looked Jewish--at least to readers of the Sturmer.

I am pretty sure that I mused about all this--I cannot be certain--as I revisited Schweidnitzerstrasse in 1961. But if memories awoke, they had to contend with a drastically changed scene. I found that neither of my first two apartment houses had survived Allied attentions. No. 5 was a hole in the ground, the site neatly cleaned up, making for a conspicuous gap between its neighbors. And No. 10, too, must have been bombed out of existence or damaged too badly to permit restoration. It had been supplanted by one of those typical post-Nazi buildings of the 1950s, unornamented, looking rather shoddy, as though its life expectancy was limited and perhaps designed to be limited, its flat surfaces broken with an array of tiny balconies on which two, at most three, people could sit to have their afternoon coffee and cake as long as they kept their elbows to themselves.

There was yet another apartment house to revisit: in 1936, when, ironically enough, my father was more prosperous than he had been for many years, we moved to Sachsische Strasse 9, a twenty-minute walk northeast of Schweidnitzerstrasse. It was a route I had taken dozens of times to visit my cousins, who lived on the Pariser Strasse, just around the corner from our new, and last German, address. This house, too, proved a casualty. The building and its attached neighbors had been razed to make way for an apartment block set thirty or more feet back from the street (evidently not even the foundations could be rescued) and dressed in the same stuccoed dreariness that had become the signature of the new Berlin.

That, then, was the return of the native. I recognized, dimly then and more clearly later, that if I wanted to take pleasure in Berlin, I would have to reconcile myself to the fact that the old city, my old city, was gone, injured perhaps beyond recovery, wounded in mind probably even more severely than in body. To be sure, I walked past concrete survivals everywhere. Most of the museums, now clustered in East Berlin, had outlived the catastrophe, though looking much the worse for wear. The city's most popular department store, the Kaufhaus des Westens (known only by the affectionate abbreviation KaDeWe) had been rebuilt largely as it had been. The Olympic stadium looked unchanged, and in general the grid of Berlin's streets remained recognizable and happily stripped of the Nazi names by which many of them were known from 1933 on. Some of these continuities were exceedingly mundane but thus all the more riveting: in my boyhood, an optometrist had gained local prominence with a terse slogan: Sind's die Augen, geh zu Ruhnke--If it's the eyes, go to Ruhnke. And Ruhnke, complete with slogan, was still in business. But were these survivals a cause for rejoicing or rejection? I did not know and was too torn to find out. All I knew was that the Nazis had poisoned my hometown as they had poisoned so much else, including me. No wonder that when, on August 2, we crossed the border on our return trip to France, my mood drastically improved. After all these years I can still summon up my sigh of relief.

- Related Categories

- BIOGRAPHY

HISTORY

![]() | My German QuestionGrowing Up in Nazi BerlinSelected as one of the Best Nonfiction Books of 1998 by theLos Angeles Times Book Review Selected as a 1998 Notable Book of the Year by the New York Times Book Review In this poignant book, a renowned historian tells of his youth as an assimilated, anti-religious Jew in Nazi Germany from 1933 to 1939—“the story,” says Peter Gay, “of a poisoning and how I dealt with it.” With his customary eloquence and analytic acumen, Gay describes his family, the life they led, and the reasons they did not emigrate sooner, and he explores his own ambivalent feelings—then and now—toward Germany and the Germans.

Gay relates that the early years of the Nazi regime were relatively benign for his family: as a schoolboy at the Goethe Gymnasium he experienced no ridicule or attacks, his father’s business prospered, and most of the family’s non-Jewish friends remained supportive. He devised survival strategies—stamp collecting, watching soccer, and the like—that served as screens to block out the increasingly oppressive world around him. Even before the events of 1938–39, culminating in Kristallnacht, the family was convinced that they must leave the country. Gay describes the bravery and ingenuity of his father in working out this difficult emigration process, the courage of the non-Jewish friends who helped his family during their last bitter months in Germany, and the family’s mounting panic as they witnessed the indifference of other countries to their plight and that of others like themselves. Gay’s account—marked by candor, modesty, and insight—adds an important and curiously neglected perspective to the history of German Jewry. Peter Gay is Sterling Professor of History Emeritus at Yale University and director of the Center for Scholars and Writers, New York Public Library. He is the author of many books, including the five-volume The Bourgeois Experience: Victoria to Freud; Freud: A Life for Our Time; A Godless Jew: Freud, Atheism, and the Making of Psychoanalysis; Voltaire’s Politics; and Reading Freud, the last three published by Yale University Press. |

The earliest known printed version of 'red-handed' is from Sir Walter Scott's

The earliest known printed version of 'red-handed' is from Sir Walter Scott's