The celebrated German author Günter Grass died seven years ago on this day, at the age of 87. His novel "The Tin Drum" was translated into 24 languages and made the Nobel laureate a household name.(德國之聲中文網)德國的納粹過去這一主題伴隨著作家君特·格拉斯(Günter Grass)的一生。在他1959年的小說處女作《鐵皮鼓》(Die Blechtrommel,please visit Youtube )中,君特·格拉斯成為最早提出德國人對納粹罪責問題的人之一。 “人們曾裝作似乎是某個幽靈來誤導了可憐的德國民眾。而我從年輕時的觀察得知,並非如此。一切都發生在光天化日之下。” 君特·格拉斯出生於1927年,從戰俘營返鄉後,格拉斯先是作石刻學徒,後入大學學習藝術。50年代中期他也以作家的身份露面。 在巴黎生活的三年裡,格拉斯的手稿《鐵皮鼓》誕生。不單是其有關罪責的主題,還有其奇异怪誕的語言在50年代末都令人震驚。格拉斯成為德國文學界不容忽視的人物。 50年代中期起,格拉斯也成為頗具影響力的作家團體“47社”(Gruppe 47)的一員。他參與社會:無論是現實政治還是對納粹過去的反省,格拉斯都成為聯邦德國的道德典範。

1999年,格拉斯到達榮譽的頂峰:他因其生平成就贏得諾貝爾獎。 2006年,格拉斯在一部自傳作品中透露,自己過去不單是德國士兵,而且在1944年後也是黨衛軍成員。對於他這麼晚才公開這一信息的指責,格拉斯予以接受。 格拉斯不畏懼發出挑釁,直到老年仍是如此。2012年4月,他發表了一則對以色列持質疑態度的詩作,受到強烈的批評。 君特·格拉斯一生打破禁忌。他的逝世令德國失去了一位鬥士和最有影響力的聲音之一。他將作為一位不屈服的作家留在人們的記憶中:他的積極參與、反抗精神以及自身的爭議都對當今德國產生了影響。

-----

【《字花》第56期・造勢的人】

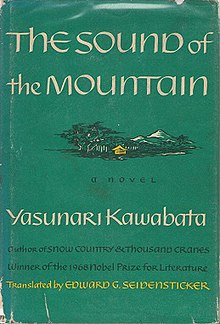

格拉斯的小說,尤其是《鐵皮鼓》,就影響深遠得多了。這是一部承先啟後之作:上承塞萬提斯(Miguel de Cervantes,1547-1616)和格里美蕭森(Hans Jakob Christoffel von Grimmelshausen,1621-1676)的流浪漢小說傳統,下開厄文(John Irving)和魯西廸(Salman Rushdie)等,崇拜者眾多,包括莫言。我們在《鐵皮鼓》中,就看到一個自私、醜陋的典型流浪漢角色,如何在一個沒有理性兼邪惡的世界,不求人生意義地活著。

//主角誕生的一幕,已清楚體現出格拉斯的「虛無主義」。通過這人物的眼睛,我們看到了納粹治下的芸芸眾生,市民紛紛穿上褐色制服,狂熱地崇拜權威;宗教向極權稱臣後,早已失去神聖的光環,但「信望愛」的歌聲依然響徹入雲。戰後經濟復甦,法西斯政治的文化遺物成了發財的企業──奧斯卡那個曾為納粹服務的鼓,戰後就成了他的賺錢工具──市民藉消費和享樂掩飾罪疚,假裝對政治漠不關心,只有在一個名為「洋蔥地窖」的酒館裏,客人切洋蔥辣出眼淚時,才能向別人吐露真情。小說由始至終,奧斯卡都處於一個抽離的位置,旁觀他人的痛苦,甚至於自己父母的死亡。不僅旁觀,更是參與,後來他厭惡一切,承認了自己沒有犯下的謀殺罪,被關進瘋人院。根據格拉斯所言,奧斯卡「是他所處時代的一面鏡子」,他「從不願長大的心態中產生的獸性、幼稚性以及犯罪」,就是那個時代的特徵。

「納粹」、「種族仇恨」、「被入侵」,這些字眼用來形容今天的香港,大概是太誇張了──抑或歷史會以各種可笑、荒誕的形式永劫回歸呢?但只要看看上面的小說撮要,我們或多或少都會有些共鳴吧。小說結尾,謀殺案水落石出,三十歲的奧斯卡將被釋放,放到哪裏去呢?有出口,却沒有出路。他想起一首令他害怕的童謠:「黑廚娘,你在嗎?在呀在呀!」//

(節錄,全文見今期《字花》)

※ ※ ※ ※

※ ※ ※ ※

56期《字花》現於序言、樂文、田園、Kubrick、榆林、三聯、商務、中華、天地、Page One、誠品等書店有售。

![]()

APRIL 13, 2015

The Greatness of Günter Grass

BY

SALMAN RUSHDIE![]()

CREDITPHOTOGRAPH BY RENE BURRI / MAGNUM

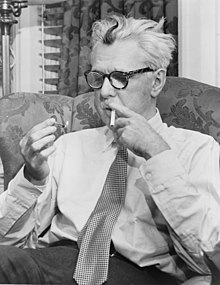

In 1982, when I was in Hamburg for the publication of the German translation of “Midnight’s Children,” I was asked by my publishers if I would like to meet Günter Grass. Well, obviously I wanted to, and so I was driven out to the village of Wewelsfleth, outside Hamburg, where Grass then lived. He had two houses in the village; he wrote and lived in one and used the other as an art studio. After a certain amount of early fencing—I was expected, as the younger writer, to make my genuflections, which, as it happened, I was happy to perform—he decided, all of a sudden, that I was acceptable, led me to a cabinet in which he stored his collection of antique glasses, and asked me to choose one. Then he got out a bottle of schnapps, and by the bottom of the bottle we were friends. At some later point, we lurched over to the art studio, and I was enchanted by the objects I saw there, all of which I recognized from the novels: bronze eels, terracotta flounders, dry-point etchings of a boy beating a tin drum. I envied him his artistic gift almost more than I admired him for his literary genius. How wonderful, at the end of a day’s writing, to walk down the street and become a different sort of artist! He designed his own book covers, too: dogs, rats, toads moved from his pen onto his dust jackets.

After that meeting, every German journalist I met wanted to ask me what I thought of him, and when I said that I believed him to be one of the two or three greatest living writers in the world some of these journalists looked disappointed, and said, “Well, ‘The Tin Drum,’ yes, but wasn’t that a long time ago?” To which I tried to reply that if Grass had never written that novel, his other books were enough to earn him the accolades I was giving him, and the fact that he had written “The Tin Drum” as well placed him among the immortals. The skeptical journalists looked disappointed. They would have preferred something cattier, but I had nothing catty to say.

I loved him for his writing, of course—for his love of the Grimm tales, which he remade in modern dress, for the black comedy he brought to the examination of history, for the playfulness of his seriousness, for the unforgettable courage with which he looked the great evil of his time in the face and rendered the unspeakable into great art. (Later, when people threw slurs at him—Nazi, anti-Semite—I thought: let the books speak for him, the greatest anti-Nazi masterpieces ever written, containing passages about Germans’ chosen blindness toward the Holocaust that no anti-Semite could ever write.)

On his seventieth birthday, many writers—Nadine Gordimer, John Irving, and the whole of German literature—assembled to sing his praises at the Thalia Theatre in Hamburg, but what I remember best is that when the praise songs were done music began to play, the theatre’s stage became a dance floor, and Grass was revealed as a master of what I call joined-up dancing. He could waltz, polka, foxtrot, tango, and gavotte, and it seemed that all the most beautiful girls in Germany were lining up to dance with him. As he delightedly swung and twirled and dipped, I understood that this was who he was: the great dancer of German literature, dancing across history’s horrors toward literature’s beauty, surviving evil because of his personal grace, and his comedian’s sense of the ridiculous as well.

To those journalists who wanted me to diss him in 1982, I said, “Maybe he has to die before you understand what a great man you have lost.” That time has now arrived. I hope they do.

The Paris Review“I have always felt we speak too much about human beings. This world is crowded with humans, but also with animals, birds, fish, and insects. They were here before we were and they will still be here should the day come when there are no more human beings.”

Günter Grass (1927–2015), The Art of Fiction no. 124, interviewed by Elizabeth Gaffney in “The Paris Review” no. 119 (Summer 1991).

![]() Paris Review - The Art of Fiction No. 124, Günter Grass

Paris Review - The Art of Fiction No. 124, Günter Grass Günter Grass (1927–2015)

THEPARISREVIEW.ORG

Günter Grass has achieved a very rare thing in contemporary arts and letters, earning both critical respect and commercial success in every genre and artistic medium he has taken up. A novelist, poet, essayist, dramatist, sculptor and graphic artist, Grass appeared on the international literary scene with the publication of his first novel, the 1958 best-seller The Tin Drum. It and his subsequent works—the novella Cat and Mouse (1961) and the novel Dog Years (1963)—are popularly known as the Danzig trilogy. His many other books include From the Diary of a Snail (1972), The Flounder (1977). The Meeting at Telgte (1979), Headbirths, or The Germans are Dying Out (1980), The Rat (1986), and Show Your Tongue(1989). Grass always designs his own book jackets, and his books often contain illustrations by the author. He has been the recipient of numerous literary prizes and medals, including the 1965 Georg Büchner Prize and the Carl von Ossietzky Medal (1977), and is a foreign honorary member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.Grass was born in 1927 on the Baltic coast, in a suburb of the Free City of Danzig, now Gdansk, Poland. His parents were grocers. During World War II he served in the German Army as a tank gunner, and was wounded and captured by American forces in 1945. After his release, he worked in a chalk mine and then studied art in Düsseldorf and Berlin. He married his first wife, the Swiss ballet dancer Anna Schwarz, in 1954. From 1955 to 1967, he participated in the meetings of Group 47, an informal but influential association of German writers and critics, so called because it first met in September of 1947. Its members, including Heinrich Böll, Uwe Johnson, Ilse Aichinger, and Grass, were organized around their common mission to develop and use a literary language that stood in radical opposition to the complex and ornate prose style characteristic of Nazi-era propaganda. They last met in 1967.

Living on a small stipend from the publishing house Luchterhand, Grass and his family spent the years 1956 to 1959 in Paris, where he wrote The Tin Drum. In 1958 he won the annual prize of Group 47 for his readings from the work in progress. The novel shocked and astounded German critics and readers, confronting them for the first time with a harsh depiction of the German bourgeoisie during the Second World War. Grass’s 1979 volume, The Meeting at Telgte, is a fictitious account of a meeting of German poets in 1647 at the close of the Thirty Years’ War. The purpose of the fictional gathering, as well as the book’s cast of characters, parallels that of the post–World War II Group 47.

In Germany, Grass has long been as well known for his controversial politics as he is for his celebrated novels. He was Willy Brandt’s chief speechwriter for ten years and is a longtime supporter of the Social Democratic Party. Lately, he has been one of the few German intellectuals to protest publicly the swift course German reunification has taken. In 1990 alone, Grass published two volumes of lectures, speeches, and debates on the subject.

When he is not traveling, he divides his time between his estate in Schleswig-Holstein where he lives with his second wife Ute Grunert and the house in the Schöneberg section of Berlin where his four children were raised and where his assistant Eva Hönisch now manages his affairs. This interview was conducted in two sessions, one before an audience at the 92nd Street YMWHA in Manhattan and one last fall at the yellow house on Niedstraβe, when Grass had found a few hours’ time during a brief stopover. He spoke in small gable-windowed study with white walls and wooden floors. The far corner was piled high with boxes of books and manuscripts. Grass was dressed comfortably, in a tweed jacket and button-down shirt. He had originally agreed to do an interview in English, thereby circumventing the complications of subsequent translation, but when reminded of this squinted his eyes and smiled, announcing, “I am much too tired! We will speak German.” Despite his professed travel-weariness, he spoke with energy and enthusiasm about his work, often laughing quietly. The interview ended when his twin sons Raoul and Franz arrived to pick their father up for a dinner to celebrate their birthday.

INTERVIEWER

How did you become a writer?

GÜNTER GRASS

I think it had something to do with the social situation in which I grew up. Ours was a lower-middle-class family; we had a small, two-room apartment. My sister and I did not have our own rooms, or even a place to ourselves. In the living room, beyond the two windows, was a little corner where my books were kept, and other things—my watercolors and so on. Often I had to imagine the things I needed. I learned very early to read amidst noise. And so I started writing and drawing at an early age. Another result is that I now collect rooms. I have a study in four different places. I’m afraid to return again to the situation of my youth, with only a corner in one small room.

INTERVIEWER

What made you turn to reading and writing in this situation, rather than, say, to sports or some other distraction?

GRASS

As a child I was a great liar. Fortunately my mother liked my lies. I promised her marvelous things. When I was ten years old she called me Peer Gynt. Peer Gynt, she said, here you are telling me marvelous stories about journeys we will make to Naples and so on . . . I started to write down my lies very early. And I continue to do so! I started a novel when I was twelve years old. It was about the Kashubians, who turned up many years later in The Tin Drum, where Oskar’s grandmother, Anna, (like my own) is Kashubian. But I made a mistake in writing my first novel: all the characters I had introduced were dead at the end of the first chapter. I couldn’t go on! This was my first lesson in writing: be careful with your characters.

INTERVIEWER

What lies have given you the greatest pleasure?

GRASS

Lies that do not hurt, which are different from lies that protect oneself or hurt another person. That is not my business. But the truth is mostly very boring, and you can help it along with lies. There is no harm in that. I have learned that all my terrible lies really have no effect on what is out there. If, several years ago, I had written something that predicted the recent political developments in Germany, people would have said, What a liar!

INTERVIEWER

What was your next effort after the failed novel?

GRASS

My first book was a book of poetry and drawings. Invariably the first drafts of my poems combine drawings and verse, sometimes taking off from an image, sometimes from words. Then, when I was twenty-five years old and could afford to buy a typewriter, I preferred to type with my two-finger system. The first version ofThe Tin Drum was done just with the typewriter. Now I’m getting older and though I hear that many of my colleagues are writing with computers, I’ve gone back to writing the first draft by hand! The first version of The Rat is in a large book of unlined paper, which I got from my printer. When one of my books is about to be published I always ask for one blind copy with blank pages to use for the next manuscript. So, these days the first version is written by hand with drawings and then the second and the third are done on a typewriter. I have never finished a book without writing three versions. Usually there are four with many corrections.

INTERVIEWER

Does each version begin at alpha and proceed to omega?

GRASS

No. I write the first draft quickly. If there’s a hole, there’s a hole. The second version is generally very long, detailed, and complete. There are no more holes, but it’s a bit dry. In the third draft I try to regain the spontaneity of the first, and to retain what is essential from the second. This is very difficult.

INTERVIEWER

What is your daily schedule when you work?

GRASS

When I’m working on the first version, I write between five and seven pages a day. For the third version, three pages a day. It’s very slow.

INTERVIEWER

You do this in the morning or in the afternoon or at night?

GRASS

Never, never at night. I don’t believe in writing at night because it comes too easily. When I read it in the morning it’s not good. I need daylight to begin. Between nine and ten o’clock I have a long breakfast with reading and music. After breakfast I work, and then take a break for coffee in the afternoon. I start again and finish at seven o’clock in the evening.

INTERVIEWER

How do you know when a book is finished?

GRASS

When I am working on an epic-length book, the writing process is fairly long. It takes from four to five years to get through all the drafts. The book is done when I am exhausted.

INTERVIEWER

Brecht was compelled to rewrite his works all the time. Even after they were published, he never considered them finished.

GRASS

I don’t think I could do that. I can only write a book like The Tin Drum orFrom the Diary of a Snail at a special period of my life. The books came about because of how I felt and thought at the time. I’m sure that if I were to sit down and rewrite The Tin Drum or Dog Years or From the Diary of a Snail I would destroy it.

INTERVIEWER

How do you distinguish your nonfiction from your fiction?

GRASS

This “fiction versus nonfiction” business is nonsense. It may be useful to booksellers to classify books by genre, but I don’t like having my books categorized that way. I’ve always imagined some committee of booksellers holding meetings to decide which books should be called fiction and which nonfiction. I say what the booksellers are doing is fiction.

INTERVIEWER

Well, when you write essays or speeches is the method, the technique different from what you use when you tell stories and make things up?

GRASS

Yes, it’s different because I am confronted with facts I cannot change. It’s not very often that I keep a diary, but I did in preparation for From the Diary of a Snail. I had the feeling that 1969 would be an important year, that it would bring about real political change beyond just ushering in a new government. So while I was on the road campaigning from March to September of 1969—a long time—I kept a diary. The same happened to me in Calcutta. The diary I kept then developed intoShow Your Tongue.

INTERVIEWER

How do you juggle your political activism with your visual art and your writing?

GRASS

Writers are involved not only with their inner, intellectual lives, but also with the process of daily life. For me, writing, drawing, and political activism are three separate pursuits; each has its own intensity. I happen to be especially attuned to and engaged with the society in which I live. Both my writing and my drawing are invariably mixed up with politics, whether I want them to be or not. I don’t actually set out with a plan to bring politics into something I’m writing. It’s much more that with the third or fourth time I scratch away at a subject, I discover things that have been neglected by history. While I would never write a story that was simply and specifically about some political reality, I see no reason to omit politics, which has such a great, determining power over our lives. It seeps into every aspect of life in one way or another.

INTERVIEWER

You incorporate so many different genres into your work—history, recipes, lyrics . . .

GRASS

. . . and drawings, poems, dialogue, quotations, speeches, letters! You see, when dealing with epic concepts I find it necessary to use every aspect of language available and the most diverse forms of linguistic communication. Remember though, that some of my books are very pure in form—the novella Cat and Mouse and The Meeting at Telgte.

INTERVIEWER

Your interlocking of words and drawing is unique.

GRASS

Drawing and writing are the primary components of my work, but not the only ones; I also sculpt when I have the time. For me, there is a very clear give-and-take relationship between art and writing. Sometimes this relationship is stronger, other times weaker. In the last few years it has been very strong. Show Your Tongue, which takes place in Calcutta, is an example of this. I could never have brought that book into existence without drawing. The incredible poverty in Calcutta constantly draws the visitor into situations where language is stifled—you cannot find words. Drawing helped me to find words again while I was there.

INTERVIEWER

In that book, the text of the poems appears not only in print, but also in handwriting superimposed on the drawings. Are the words to be considered a graphic element and a part of the drawings?

GRASS

Some elements of the poems were formulated or suggested by the drawings. When words finally came to me, I began to write on top of what I had drawn—text and drawing superimposed on one another. If you can make out the words in the drawings, that’s fine; they are there to be read. But the drawings generally contain early drafts, what I first wrote by hand before sitting myself down at the typewriter. It was very difficult to write this book, and I’m not sure why. Perhaps it was the subject, Calcutta. I have been there twice. The first time was eleven years before I began Show Your Tongue. It was my first time in India. I spent only a few days in Calcutta. I was shocked. There was, from the beginning, the wish to come back, to stay longer, to see more, to write things down. I went on other voyages—in Asia, Africa—but whenever I saw the slums of Hong Kong or Manila or Jakarta, I was reminded of the situation in Calcutta. There is no other place I know where the problems of the first world are so openly mixed up with those of the third, out in the in daylight.

So I went to Calcutta again, and I lost my ability to use language. I couldn’t write a word. At this point the drawing became important. It was another way of trying to capture the reality of Calcutta. With the help of the drawings I was finally able to write prose again—that is the first section of the book, a kind of essay. After that I began work on the third section, a long poem of twelve parts. It is a city poem, about Calcutta. If you look at the prose, drawings and poem together, you see that they deal with Calcutta in related but separate ways. There is a dialogue among them, although the textures of the three are very different.

INTERVIEWER

Is any one of these textures more important than the others?

GRASS

I can answer, only for myself, that poetry is the most important thing. The birth of a novel begins with a poem. I will not say it is ultimately more important, but I can’t do without it. I need it as a starting point.

INTERVIEWER

A more dignified art form, perhaps, than the others?

GRASS

No, no, no! Prose, poetry, and drawings stand side by side in a very democratic way in my work.

INTERVIEWER

Is there something physical, sensual about the act of drawing that is absent from the process of writing?

GRASS

Yes. Writing is a genuinely laborious and abstract process. When it is fun, the pleasure is wholly different from the pleasure of drawing. With drawing, I am acutely aware of creating something on a sheet of paper. It is a sensual act, which you cannot say about the act of writing. In fact, I often turn to drawing to recover from the writing.

INTERVIEWER

Writing is so unpleasant and painful?

GRASS

It’s a bit like sculpting. With sculpture, you have to work from every side. If you change something here, you have to change something there. Suddenly you change one plane . . . and the sculpture becomes something! There is some music in it. The same can happen with a piece of writing. I can work for days on the first or second or third draft, or on a long sentence, or just one period. I like periods, as you know. I work and I work and it’s all right. Everything’s in there, but there’s something heavy about it. Then I make a few changes, which I don’t think are very important, and it works! This is what I understand happiness to be, something like happiness. It lasts for two or three seconds. Then I look ahead to the next period, and it’s gone.

INTERVIEWER

To return to poetry for a moment, do poems that you write as parts of novels differ in some way from autonomous ones?

GRASS

At one time I was very old fashioned about writing poetry. I thought that when you have enough good poems, you should go out and look for a publisher, do some drawings and print a book. Then you’d have this marvelous volume of poetry, quite isolated, only for lovers of poetry. Then beginning with From the Diary of a Snail, I began to put poetry and prose together on the pages of my books. This poetry has a different tone. I don’t see any reason to isolate poetry from prose, especially when we have in the German literary tradition such a wonderful mixture of the two genres. I have become increasingly interested in putting poetry between the chapters and using it to define the texture of the prose. Besides, there’s the chance that prose readers who have the feeling that “poetry is too heavy for me” will see how much simpler and easier poetry can sometimes be than prose.

INTERVIEWER

How much do English-speaking readers lose by reading your books in English?

GRASS

That’s very difficult for me answer—I am not an English reader. But I do try to help out with the translations. When I went over the manuscript of The Flounderwith my German publisher, I asked for a new contract. It stipulates that once I have finished a manuscript and my translators have studied it, my publisher organizes and pays for a meeting for all of us. We did it first with The Flounder, then with The Meeting at Telgte, and with The Rat too. I think it is a great help. The translators know everything about my books and ask marvelous questions. They know the books even better than I do. This can sometimes be unpleasant for me, because they also find the flaws in the books and tell me about them. The French, Italian, and Spanish translators compare notes at these meetings and have found that their collaboration helps all of them bring the books into their own languages. I certainly prefer translations that I can read without being aware that I am reading a translation. In the German language we are lucky to have marvelous translations from Russian literature. The Tolstoy and the Dostoyevsky translations are perfect—they’re really part of German literature. The Shakespeare translations and those of the romantic authors are full of mistakes, but they too are marvelous. Newer translations of those works have fewer mistakes, perhaps none, but can’t be compared to the Friedrich von Schlegel–Ludwig Tieck translations. A literary book, whether it is poetry or a novel, needs a translator who is able to recreate the book within his own language. I try to encourage my translators to do this.

INTERVIEWER

Do you think your novel Die Rättin suffered somehow in English because the title had to be The Rat and therefore did not convey that it is a female rat? “The She-Rat” would not have sounded right to American ears and “Rattessa” is out of the question. The reference to a specifically female rat seems so fascinating, whereas the genderless English word rat conjures up everyday images of those ugly beasts that infest the subways.

GRASS

We did not have this word in the German language either. I created it. I always try to encourage my translators to invent. I tell them, If this word doesn’t exist in your language, create it. Actually, for me it has a nice sound, she-rat.

INTERVIEWER

Why is the rat in the book a female rat? Is that for erotic or feminist or political reasons?

GRASS

In The Flounder it’s a male. But as I get older I see that I’ve really given myself over to women. I will not change that. Whether it’s a human woman or a rat—a she-rat—it doesn’t matter. I get ideas, you see? They make me jump and dance, and then I find words and stories, and I begin to lie. It’s very important to lie. It makes no sense for me to lie to a man—to sit with a man, together, telling lies—but with a woman!

INTERVIEWER

So many of your books, like The Rat, The Flounder, From the Diary of a Snail,or Dog Years, center on an animal. Is there some special reason for that?

GRASS

Perhaps. I have always felt we speak too much about human beings. This world is crowded with humans, but also with animals, birds, fish, and insects. They were here before we were and they will still be here should the day come when there are no more human beings. There is one difference between us: in our museums we have the bones of the dinosaurs, enormous animals that lived for many millions of years. And when they died, they died in a very clean way. No poison at all. Their bones are very clean. We can see them. This will not happen with human beings. When we die there will be a terrible breath of poison. We must learn that we are not alone on the earth. The Bible teaches a bad lesson when it says that man has dominion over the fish, the fowl, the cattle, and every creeping thing. We have tried to conquer the earth, with poor results.

INTERVIEWER

Have you ever learned from criticism?

GRASS

Although I like to think I am a good pupil, critics are not usually very good teachers. Yet there was one period, which I sometimes miss, when I learned from critics. It was the period of Group 47. We read aloud from manuscripts and discussed them. That’s where I learned to discuss a text and give reasons for my opinions, rather than just saying, “I like that.” The critique came spontaneously. The authors would discuss craft, how to write a book, that sort of thing. As for the critics, they had their own expectations as to how an author should write. This mixture of critics and authors was altogether a good experience for me, and a lesson. In fact, that period was important for postwar German literature in general. There was so much confusion after the war, especially in literary circles, because the generation that grew up during the war—my generation—was either uneducated or miseducated. The language was tainted. The significant authors had emigrated. No one expected anything of German literature. The annual meetings of Group 47 provided a context for us from which German literature could re-emerge. Many German authors of my generation were marked by Group 47, although some don’t admit it.

INTERVIEWER

What about criticism published, say, in magazines or newspapers or books? Did that ever affect you?

GRASS

No. But I learned from other authors. Alfred Döblin had such an effect on me that I wrote an essay on him entitled “On My Teacher Döblin.” You can learn from Döblin without the risk of imitating him. For me, he was much more important than Thomas Mann. Döblin’s novels are not as symmetrical, not as classically formed as Mann’s, and the risks he took were greater. His books are rich, open, full of ideas. I’m sorry that in both America and Germany he is known almost exclusively for Berlin Alexanderplatz. But I am still learning, and there are many others who have taught me.

INTERVIEWER

What about American authors?

GRASS

Melville has always been my favorite. And I’ve very much enjoyed reading William Faulkner, Thomas Wolfe, and John Dos Passos. There is no one like Dos Passos—with his marvelous depictions of the masses—writing in America now. I miss the epic dimension that once existed in American literature; it has become over-intellectualized.

INTERVIEWER

What do you think of the movie version of The Tin Drum?

GRASS

Schlöndorff made a good film, even though he didn’t follow the literary form of the book. Perhaps that was necessary, because the point of view of Oskar—who tells his story by constantly jumping from one time period to another—would make a very complicated film. Schlöndorff did something very simple. He just tells the story on one line. There are, of course, whole sections that Schlöndorff cut from the movie version. I miss some of those. And there are aspects of the film I don’t like much at all. The short scenes in the Catholic church don’t quite work because Schlöndorff doesn’t understand anything about Catholicism. He is really a German Protestant, and the Catholic church in the movie looks like a Protestant church that happens to have a confessional in it. But this is one small detail. Altogether, and with the help of the young boy who played Oskar, I think it’s a good film.

INTERVIEWER

You have a special interest in the grotesque—I am thinking especially of the famous scene with the eels squirming out of the horse’s head in The Tin Drum. Where does that come from?

GRASS

That comes from me. I have never understood why this passage, which is six pages long, is so disturbing. It is a piece of fantastical reality, which I wrote just the same way I go about writing any other detail. But the death and sexuality that are evoked by that image have generated an enormous disgust in people.

INTERVIEWER

What impact has the reunification of Germany had on German cultural life?

GRASS

Nobody listened to the German artists and writers that spoke out against it. Unfortunately the majority of intellectuals did not enter into the discussion, whether for reasons of laziness or apathy I don’t know. Early on, the former chancellor, Willy Brandt, pronounced that the train to German unity had left the station and no one could stop it. An unreflective mass enthusiasm took over. That idiotic metaphor was taken as the truth; it ensured that no one thought about how badly this would damage East German culture, not to mention their economy. No, I do not wish to ride a train that cannot be steered and does not respond to warning signals. I have remained standing on the platform.

INTERVIEWER

How do you react to the sharp criticism you have endured from the German press for your views on reunification?

GRASS

Oh, I am used to that! It doesn’t affect my position. Reunification has been carried out in a manner that violates our basic law. A new constitution should have been drafted when the divided German states came together again—a constitution appropriate to the problems of a united Germany. We did not get a new constitution. What happened instead was that all the East German states were annexed to West Germany. This was done using a sort of a loophole, an article of the constitution that was intended to enable individual German states to become part of West Germany. It also grants the right of West German citizenship to ethnic Germans, such as defectors from the East. It’s a real problem because not everything about East Germany was corrupt, just the government. And now everything East German—including their schools, their art, their culture—is going to be tossed out or suppressed. It has been stigmatized; that entire part of German culture will vanish.

INTERVIEWER

German unification is the kind of historical event that you frequently take up in your books. When you write about such situations, do you attempt to give a “true” historical narrative? How do fictional histories like yours complement the history we read in textbooks and newspapers?

GRASS

History is more than the news. I have concerned myself particularly with the progression of historical events in two books, The Meeting at Telgte and The Flounder. In The Flounder, it’s the story of the historical development of human nourishment. There’s not a great deal of material on that subject—we usually call only those things history that have to do with war, peace, political oppression, or party politics. The process of nourishment and human nutrition is a central question, especially important now, when starvation and the population explosion go hand in hand in the third world. Anyway, I had to invent the documentation for this history, and decided upon using a fairy tale as the guiding metaphor. Fairy tales generally speak the truth, encapsulating the essence of our experiences, dreams, wishes, and our sense of being lost in the world. In this way they are truer than many facts.

INTERVIEWER

What about your characters?

GRASS

Literary characters, and especially the protagonist who must carry a book, are combinations of many different people, ideas, experiences, all bundled together. As a writer of prose you have to create, invent characters—some you like and others you don’t. You can only do it successfully if you can get inside these people. If I don’t understand my own creations from the inside, they will be paper figures, nothing more.

INTERVIEWER

They frequently make reappearences in several different books; I’m thinking again of Tulla, Ilsebill, Oskar, and his grandmother Anna, for example. I get the impression that these characters are all members of a larger fictive world that you have only just begun to document in your novels. Do you ever think of them as having an independent existence?

GRASS

When I begin a book I develop sketches of several different characters. As my work on the book progresses, these fictive characters often begin to live their own lives. For example, in The Rat I had never planned to reintroduce Mr. Matzerath as a sixty-year-old man. But he presented himself to me, kept asking to be included, saying, I am still here; this is also my story. He wanted to get into the book. I have often found that over the course of years, these invented people begin to make demands, contradict me, or even refuse to allow themselves to be used. One is well advised to take heed of these people now and then. Of course, one must also listen to one’s self. It becomes a kind of dialogue, sometimes a very heated one. It is cooperation.

INTERVIEWER

Why is the character Tulla Pokriefke at the center of so many of your books?

GRASS

Her character is so difficult and full of contradictions. I was very much touched when I wrote those books. I can’t explain her. If I did, there would be an explanation. I hate explanations! I invite you to make your own picture. In Germany the high-school kids come to school and what they want is to read a good story or a book with a redhead in it! But that’s not allowed. Instead they are instructed to interpret every poem, every page, to discover what the poet is saying. This has nothing to do with art. You can explain a technical thing and its function, but a picture or a poem or a story or a novel has so many possibilities. Every reader creates a poem over again. That’s the reason I hate interpretations and explanations. Still, I’m very glad that you’re still in touch with Tulla Pokriefke.

INTERVIEWER

Your books are often told from many points of view. In The Tin Drum, Oskar speaks from the first person and the third person. In Dog Years, the narrative switches from second to third person. One could go on. How does this technique help you to present your view of the world?

GRASS

One must always seek out fresh perspectives. For example, Oskar Matzerath. A dwarf—a child even in adulthood—his size and his passivity make him a perfect vehicle for many different perspectives. He has delusions of grandeur, and that is why he sometimes speaks of himself in the third person, just as young children sometimes do. It is part of his self-glorification. It is like the royal we, and in the spirit of de Gaulle, saying, “moi, de Gaulle . . .” These are all narrative postures that provide distance. In Dog Years, there are three perspectives, with the role of the dog different in each. The dog is a point of refraction.

INTERVIEWER

How have your interests changed and your style developed over the course of your career?

GRASS

My first three major books, The Tin Drum, Dog Years, and the novella Cat and Mouse, represent one period—the sixties. The German experience of World War II is central to all three books, which together make up the Danzig trilogy. At that time I felt especially compelled to deal with the Nazi era in my writing, to work through its causes and ramifications. A few years later, I wrote From the Diary of a Snail, which also deals with the war, but was a real departure in terms of my prose style and form. The action takes place in three different epochs: the past (World War II), the present (1969 in Germany, when I began work on the book), and the future (represented by my children). In my head and in the book all these time periods are jumbled together. I discovered that the verb tenses taught in grammar school—past, present, and future—are not so simple in real life. Every time I think about the future, my knowledge of the past and the present are there, affecting what I call future. And sentences that were said yesterday may not really be past and done with—perhaps they will have a future. Mentally, we are not restricted to chronology—we are aware of many different times at once, as if they were one. As a writer, I have to perceive this overlapping of times and tenses and be able to present it. These temporal themes have become increasingly important in my work. Headbirths, or the Germans are Dying Out is really narrated from a new, invented time, which I callVergegenkunft. It’s an amalgam of the words past, present, and future. In German, you can run words together to form compounds. Ver- comes from Vergangenheit, which means “past”; -gegen- from Gegenwart, which means “present”; and -kunftfrom Zukunft, the word for “future.” This new, mixed-up time is also central to The Flounder. In that book the narrator has been reincarnated over and over again throughout time, and his many different biographies provide new perspectives, each in its own present tense. To write a book from the perspectives of so many different eras, looking back from the present and in touch with things to come, I thought I would need a new form. But the novel is such an open form, that I found I could shift forms, from poetry to prose, within it.

INTERVIEWER

In From the Diary of a Snail, you combine contemporary politics with a fictionalized account of what befell the Jewish community of Danzig during the Second World War. Did you know that the speechwriting and electioneering you did for Willy Brandt in 1969 would become material for a book?

GRASS

I had no other choice but to go on that election campaign, book or not. Born in 1927, in Germany, I was twelve years old when the war started and seventeen years old when it was over. I am overloaded with this German past. I’m not the only one; there are other authors who feel this. If I had been a Swedish or a Swiss author I might have played around much more, told a few jokes and all that. That hasn’t been possible; given my background, I have had no other choice. In the fifties and the sixties, the Adenauer period, politicians didn’t like to speak about the past, or if they did speak about it, they made it out to be a demonic period in our history when devils had betrayed the pitiful, helpless German people. They told bloody lies. It has been very important to tell the younger generation how it really happened, that it happened in daylight, and very slowly and methodically. At that time, anyone could have looked and seen what was going on. One of the best things we have after forty years of the Federal Republic is that we can talk about the Nazi period. And postwar literature played an important part in bringing that about.

INTERVIEWER

The Diary of a Snail begins, “Dear children.” This is an appeal to the entire generation that grew up after the war, but you are also addressing your own children.

GRASS

I wanted to explain how the transgression of genocide came about. Born after the war, my children had a father who drove off to campaign and give speeches on Monday morning and did not come back again until the following Saturday. They asked, “Why do you do this, why are you constantly away from us?” I tried to make it clear to them, not only verbally, but in what I wrote. The incumbent chancellor at that time, Kurt Georg Kiesinger, had been a Nazi during the war. So I was not only campaigning for a new German chancellor, but also against the Nazi past. In my book I didn’t want to stick merely to abstract numbers—“so and so many Jews were murdered.” Six million is an incomprehensible number. I wanted it to have a more physical impact. So I chose as the thread to my story the history of the Danzig synagogue, which stood in that city for many centuries until it was destroyed during the war by the Nazis—Germans. I wanted to document the truth of what happened there. In the final scene of the book I relate this to the present; I write about my preparations for a lecture given in honor of Albrecht Dürer’s three hundredth birthday. The chapter is a melancholy reflection on Dürer’s engraving Melencholia Iand the effect melancholy has had on human history. I imagine that a culture-wide state of melancholy would be the correct attitude for Germans to have toward the Holocaust. Repentant and mournful, it would be informed by some insight about the causes of the Holocaust, which would carry over to our times as a lesson.

INTERVIEWER

This is typical of so many of your books, focusing on some aspect of wretchedness in the current world situation and the horrors that seem to lie ahead. Do you mean to teach, to warn, or to incite your readers to some kind of action?

GRASS

Simply, I do not want to deceive them. I want to present the situation they are in, or one they may look forward to. People are disconsolate, not because everything is so awful but because we as human beings have it in our hands to change things, but don’t. Our problems are caused by us, determined by us, and it behooves us to solve them.

INTERVIEWER

Your activism extends to environmental as well as political issues, and you have incorporated this into your work.

GRASS

In the past few years I have traveled a great deal, in Germany and other places. I have seen and drawn dying, poisoned worlds. I published a book of drawings calledDeath of Wood about one such world, on the border between the Federal Republic of Germany and what was then still the German Democratic Republic. There, well in advance of the political union, a reunification of Germany occurred in the form of dying forests. This is also true of the mountain range on the border of West Germany and Czechoslovakia. It looks as if a slaughter had taken place. I drew what I saw there. The pictures have brief, pregnant titles that are intended more as commentary than description, and there is an afterword. With this kind of subject matter, drawing has an equal or greater weight than the writing.

INTERVIEWER

Do you believe that literature has sufficient power to illuminate the political realities of an age? Did you go into politics because as a citizen you felt you could do more than what you could as a writer?

Günter GRASS

I don’t think politics should be left to the parties; that would be dangerous. There are so many seminars and conferences on the subject “can literature change the world”! I think literature has the power to effect change. So does art. We’ve changed our habits of seeing as a result of modern art, in ways of which we are barely aware. Inventions like cubism have provided us with new powers of vision. James Joyce’s introduction of the interior monologue in Ulysses has affected the complexity of our understanding of existence. It’s just that the changes that literature can affect are not measurable. The intercourse between a book and its reader is peaceful, anonymous.

To what extent have books changed people? We don’t know much about this. I can only answer that books have been decisive for me. When I was young, after the war, one of the many books that were important for me was that little volume by Camus, The Myth of Sisyphus. The famous, mythological hero who is sentenced to roll a stone up a mountain, which inevitably rolls back down to the bottom—traditionally a genuinely tragic figure—was newly interpreted for me by Camus as being happy in his fate. The continuous, futile-seeming repetition of rolling the stone up the mountain is actually the satisfying act of his existence. He would be unhappy if someone took the stone away from him. That had a great influence on me. I don’t believe in an end goal; I don’t think the stone will ever remain at the top of the mountain. We can take this myth to be a positive depiction of the human condition, even though it stands in opposition to every form of idealism, including German idealism, and to every ideology. Every Western ideology promises some ultimate goal—a happy, a just, or a peaceful society. I don’t believe in that. We are things in flux. It may be that the stone always slides away from us and must be rolled back up again, but it’s something we must do; the stone belongs to us.

INTERVIEWER

So how do you envision man’s future?

GRASS

As long as we are needed, there will be some sort of future. I can’t tell you much about it in one word. I don’t want to give an answer to this in one word. I have written a book, The Rat—“The She-Rat,” “Rattessa.” What else do you want? It is a long answer to your question.

Author photograph by Nancy Crampton.

この画像を表示

この画像を表示