《零八憲章》是為了紀念2008年12月10日《世界人權宣言》發表60周年由劉曉波等人起草並由303位中國各界人士首批簽署的一份宣言,旨在促進中國民主化進程,改善人權狀況。由於內容敏感,迄12月11日止發起人中已有兩人因此事被中華人民共和國政府逮捕。到目前為止,在《零八憲章》上簽名的有八千多人,還有一些人陸續在網上簽名。不過由於網站受到當局干擾,所以即使在網上簽名也已經不容易。

起草人在宣言開頭解釋了發佈

《零八憲章》的立場:

今年是中國立憲百年,《世界人權宣言》公布60周年,「民主牆」誕生30周年,中國政府簽署《公民權利和政治權利國際公約》10周年。在經歷了長期的人權災難和艱難曲折的抗爭歷程之後,覺醒的中國公民日漸清楚地認識到,自由、平等、人權是人類共同的普世價值;民主、共和、憲政是現代政治的基本制度架構。

過程零八憲章由中國303名各界人士發起並簽署。為因應世界人權宣言60周年,中國的維權人士呼籲在自由、平等、人權的普世價值下,在中國實施民主、共和、憲政的現代政治架構。原定於2008年12月10日簽署《世界人權宣言》60周年這一天舉行論壇,並發表中國《零八憲章》。不過因為當局的逮捕行動而終止。

簽署者除發起人劉曉波以外,尚有

鮑彤、丁子霖、戴晴、於浩成、浦志強、張祖樺、茅於軾、冉雲飛、劉逸明等,包括一些中國著名異見人士與維權人士。[5]

宣言內容《零八憲章》分「前言」、「我們的基本理念」、「我們的基本主張」和「結語」等四部分,主要內容是闡述自由、人權、民主、憲政等概念,主張修改憲法、實行分權制衡,實現立法民主,司法獨立,主張結社、集會、言論、宗教自由,宣言共提出6點理念與19點的主張。

基本理念* 自由:言論、出版、信仰、集會、結社、遷徙、罷工和遊行示威等權利

* 人權:人是國家的主體,國家服務於人民,政府為人民而存在。

* 平等:公民不論社會地位、職業、性別、經濟狀況、種族、膚色、宗教或政治信仰,其人格、尊嚴、自由都是平等的。

* 共和:要求「大家共治,和平共生」,分權制衡與利益平衡。

* 民主:主權在民和民選政府。

* 憲政:主張以法治限制政府權力和行為的邊界。

十九點基本主張《零八憲章》提出了十九點基本主張,包括:

1. 修改憲法

2. 分權制衡

3. 立法民主

4. 司法獨立

5. 公器公用

6. 人權保障

7. 公職選舉

8. 城鄉平等

9. 結社自由

10. 集會自由

11. 言論自由

12. 宗教自由

13. 公民教育

14. 財產保護

15. 財稅改革

16. 社會保障

17. 環境保護

18. 聯邦共和

19. 轉型正義

內容觸及了政治改革、經濟改革、城鄉差距與環境保護等諸多方面。

政府壓制《零八憲章》發布至今,不斷有人加入簽署者行列。與此同時,中國政府也在採取打壓行動。首先是《零八憲章》共同起草人之一劉曉波被起訴。北京大學法學院教授

賀衛方最近被調往新疆石河子支教。雖然原因無法確定,但有人認為可能和憲章有關。另外一位在《零八憲章》上簽名的北大教授

夏業良受到很大的壓力,在兩個學術組織的職務被撤銷。

其他許多簽署人也被警方傳喚,要求他們退出。據維權網報導,3月23日,四川自貢市簽署人羅世模被當地警方刑事傳喚,問及有關簽署《零八憲章》的情況。另外,廣東省韶關民運人士羅勇泉因為簽署《零八憲章》4月1日遭韶關市南雄縣國保大隊傳喚,這已經是半個月來第二次。

據很多簽署人反映,警方在傳訊他們的時候都做了筆錄,問話內容圍繞《零八憲章》共同起草人劉曉波以及簽署前後的情況。

在海外,該聲明則得到了

余英時、哈金、陳一諮、方勵之、胡平、宋永毅、蘇曉康、萬潤南、王丹等多位著名人士的支持。

簽署人表示,他們這樣做,是為了表達他們就中國未來向何處去這個問題的一種共識,希望民眾了解他們的民主訴求,但他們並不奢求能夠很快實現所追求的目標.

中共在國內各媒體網站對此憲章全面封鎖,禁止報導。有消息稱北京大學法學院以黨委名義發布群郵件要求該院學生抵制零八憲章。

國際反應2009年3月11日,在布拉格開幕的2009年「同一個世界」人權電影節開幕式上,捷克前總統哈維爾親自將「人與人」(Homo Homini)人權獎授予劉曉波和《零八憲章》簽署群體。由於劉曉波因故不能出席,參與簽署《零八憲章》的中國哲學家徐友漁、學者崔衛平和律師莫少平代替劉曉波接受了這一獎項。

China's Charter 08Translated from the Chinese by Perry LinkThe document below, signed by more than two thousand Chinese citizens, was conceived and written in conscious admiration of the founding of Charter 77 in Czechoslovakia, where, in January 1977, more than two hundred Czech and Slovak intellectuals formed a

loose, informal, and open association of people...united by the will to strive individually and collectively for respect for human and civil rights in our country and throughout the world.

The Chinese document calls not for ameliorative reform of the current political system but for an end to some of its essential features, including one-party rule, and their replacement with a system based on human rights and democracy.

The prominent citizens who have signed the document are from both outside and inside the government, and include not only well-known dissidents and intellectuals, but also middle-level officials and rural leaders. They chose December 10, the anniversary of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, as the day on which to express their political ideas and to outline their vision of a constitutional, democratic China. They want Charter 08 to serve as a blueprint for fundamental political change in China in the years to come. The signers of the document will form an informal group, open-ended in size but united by a determination to promote democratization and protection of human rights in China and beyond.

Following the text is a postscript describing some of the regime's recent reactions to it.

—Perry Link

I. FOREWORDA hundred years have passed since the writing of China's first constitution. 2008 also marks the sixtieth anniversary of the promulgation of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the thirtieth anniversary of the appearance of the Democracy Wall in Beijing, and the tenth of China's signing of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. We are approaching the twentieth anniversary of the 1989 Tiananmen massacre of pro-democracy student protesters. The Chinese people, who have endured human rights disasters and uncountable struggles across these same years, now include many who see clearly that freedom, equality, and human rights are universal values of humankind and that democracy and constitutional government are the fundamental framework for protecting these values.

By departing from these values, the Chinese government's approach to "modernization" has proven disastrous. It has stripped people of their rights, destroyed their dignity, and corrupted normal human intercourse. So we ask: Where is China headed in the twenty-first century? Will it continue with "modernization" under authoritarian rule, or will it embrace universal human values, join the mainstream of civilized nations, and build a democratic system? There can be no avoiding these questions.

The shock of the Western impact upon China in the nineteenth century laid bare a decadent authoritarian system and marked the beginning of what is often called "the greatest changes in thousands of years" for China. A "self-strengthening movement" followed, but this aimed simply at appropriating the technology to build gunboats and other Western material objects. China's humiliating naval defeat at the hands of Japan in 1895 only confirmed the obsolescence of China's system of government. The first attempts at modern political change came with the ill-fated summer of reforms in 1898, but these were cruelly crushed by ultraconservatives at China's imperial court. With the revolution of 1911, which inaugurated Asia's first republic, the authoritarian imperial system that had lasted for centuries was finally supposed to have been laid to rest. But social conflict inside our country and external pressures were to prevent it; China fell into a patchwork of warlord fiefdoms and the new republic became a fleeting dream.

The failure of both "self- strengthening" and political renovation caused many of our forebears to reflect deeply on whether a "cultural illness" was afflicting our country. This mood gave rise, during the May Fourth Movement of the late 1910s, to the championing of "science and democracy." Yet that effort, too, foundered as warlord chaos persisted and the Japanese invasion [beginning in Manchuria in 1931] brought national crisis.

Victory over Japan in 1945 offered one more chance for China to move toward modern government, but the Communist defeat of the Nationalists in the civil war thrust the nation into the abyss of totalitarianism. The "new China" that emerged in 1949 proclaimed that "the people are sovereign" but in fact set up a system in which "the Party is all-powerful." The Communist Party of China seized control of all organs of the state and all political, economic, and social resources, and, using these, has produced a long trail of human rights disasters, including, among many others, the Anti-Rightist Campaign (1957), the Great Leap Forward (1958–1960), the Cultural Revolution (1966–1969), the June Fourth [Tiananmen Square] Massacre (1989), and the current repression of all unauthorized religions and the suppression of the weiquan rights movement [a movement that aims to defend citizens' rights promulgated in the Chinese Constitution and to fight for human rights recognized by international conventions that the Chinese government has signed]. During all this, the Chinese people have paid a gargantuan price. Tens of millions have lost their lives, and several generations have seen their freedom, their happiness, and their human dignity cruelly trampled.

During the last two decades of the twentieth century the government policy of "Reform and Opening" gave the Chinese people relief from the pervasive poverty and totalitarianism of the Mao Zedong era, and brought substantial increases in the wealth and living standards of many Chinese as well as a partial restoration of economic freedom and economic rights. Civil society began to grow, and popular calls for more rights and more political freedom have grown apace. As the ruling elite itself moved toward private ownership and the market economy, it began to shift from an outright rejection of "rights" to a partial acknowledgment of them.

In 1998 the Chinese government signed two important international human rights conventions; in 2004 it amended its constitution to include the phrase "respect and protect human rights"; and this year, 2008, it has promised to promote a "national human rights action plan." Unfortunately most of this political progress has extended no further than the paper on which it is written. The political reality, which is plain for anyone to see, is that China has many laws but no rule of law; it has a constitution but no constitutional government. The ruling elite continues to cling to its authoritarian power and fights off any move toward political change.

The stultifying results are endemic official corruption, an undermining of the rule of law, weak human rights, decay in public ethics, crony capitalism, growing inequality between the wealthy and the poor, pillage of the natural environment as well as of the human and historical environments, and the exacerbation of a long list of social conflicts, especially, in recent times, a sharpening animosity between officials and ordinary people.

As these conflicts and crises grow ever more intense, and as the ruling elite continues with impunity to crush and to strip away the rights of citizens to freedom, to property, and to the pursuit of happiness, we see the powerless in our society—the vulnerable groups, the people who have been suppressed and monitored, who have suffered cruelty and even torture, and who have had no adequate avenues for their protests, no courts to hear their pleas—becoming more militant and raising the possibility of a violent conflict of disastrous proportions. The decline of the current system has reached the point where change is no longer optional.

II. OUR FUNDAMENTAL PRINCIPLESThis is a historic moment for China, and our future hangs in the balance. In reviewing the political modernization process of the past hundred years or more, we reiterate and endorse basic universal values as follows:

Freedom. Freedom is at the core of universal human values. Freedom of speech, freedom of the press, freedom of assembly, freedom of association, freedom in where to live, and the freedoms to strike, to demonstrate, and to protest, among others, are the forms that freedom takes. Without freedom, China will always remain far from civilized ideals.

Human rights. Human rights are not bestowed by a state. Every person is born with inherent rights to dignity and freedom. The government exists for the protection of the human rights of its citizens. The exercise of state power must be authorized by the people. The succession of political disasters in China's recent history is a direct consequence of the ruling regime's disregard for human rights.

Equality. The integrity, dignity, and freedom of every person—regardless of social station, occupation, sex, economic condition, ethnicity, skin color, religion, or political belief—are the same as those of any other. Principles of equality before the law and equality of social, economic, cultural, civil, and political rights must be upheld.

Republicanism. Republicanism, which holds that power should be balanced among different branches of government and competing interests should be served, resembles the traditional Chinese political ideal of "fairness in all under heaven." It allows different interest groups and social assemblies, and people with a variety of cultures and beliefs, to exercise democratic self-government and to deliberate in order to reach peaceful resolution of public questions on a basis of equal access to government and free and fair competition.

Democracy. The most fundamental principles of democracy are that the people are sovereign and the people select their government. Democracy has these characteristics: (1) Political power begins with the people and the legitimacy of a regime derives from the people. (2) Political power is exercised through choices that the people make. (3) The holders of major official posts in government at all levels are determined through periodic competitive elections. (4) While honoring the will of the majority, the fundamental dignity, freedom, and human rights of minorities are protected. In short, democracy is a modern means for achieving government truly "of the people, by the people, and for the people."

Constitutional rule. Constitutional rule is rule through a legal system and legal regulations to implement principles that are spelled out in a constitution. It means protecting the freedom and the rights of citizens, limiting and defining the scope of legitimate government power, and providing the administrative apparatus necessary to serve these ends.

III. WHAT WE ADVOCATEAuthoritarianism is in general decline throughout the world; in China, too, the era of emperors and overlords is on the way out. The time is arriving everywhere for citizens to be masters of states. For China the path that leads out of our current predicament is to divest ourselves of the authoritarian notion of reliance on an "enlightened overlord" or an "honest official" and to turn instead toward a system of liberties, democracy, and the rule of law, and toward fostering the consciousness of modern citizens who see rights as fundamental and participation as a duty. Accordingly, and in a spirit of this duty as responsible and constructive citizens, we offer the following recommendations on national governance, citizens' rights, and social development:

1. A New Constitution. We should recast our present constitution, rescinding its provisions that contradict the principle that sovereignty resides with the people and turning it into a document that genuinely guarantees human rights, authorizes the exercise of public power, and serves as the legal underpinning of China's democratization. The constitution must be the highest law in the land, beyond violation by any individual, group, or political party.

2. Separation of Powers. We should construct a modern government in which the separation of legislative, judicial, and executive power is guaranteed. We need an Administrative Law that defines the scope of government responsibility and prevents abuse of administrative power. Government should be responsible to taxpayers. Division of power between provincial governments and the central government should adhere to the principle that central powers are only those specifically granted by the constitution and all other powers belong to the local governments.

3. Legislative Democracy. Members of legislative bodies at all levels should be chosen by direct election, and legislative democracy should observe just and impartial principles.

4. An Independent Judiciary. The rule of law must be above the interests of any particular political party and judges must be independent. We need to establish a constitutional supreme court and institute procedures for constitutional review. As soon as possible, we should abolish all of the Committees on Political and Legal Affairs that now allow Communist Party officials at every level to decide politically sensitive cases in advance and out of court. We should strictly forbid the use of public offices for private purposes.

5. Public Control of Public Servants. The military should be made answerable to the national government, not to a political party, and should be made more professional. Military personnel should swear allegiance to the constitution and remain nonpartisan. Political party organizations must be prohibited in the military. All public officials including police should serve as nonpartisans, and the current practice of favoring one political party in the hiring of public servants must end.

6. Guarantee of Human Rights. There must be strict guarantees of human rights and respect for human dignity. There should be a Human Rights Committee, responsible to the highest legislative body, that will prevent the government from abusing public power in violation of human rights. A democratic and constitutional China especially must guarantee the personal freedom of citizens. No one should suffer illegal arrest, detention, arraignment, interrogation, or punishment. The system of "Reeducation through Labor" must be abolished.

7. Election of Public Officials. There should be a comprehensive system of democratic elections based on "one person, one vote." The direct election of administrative heads at the levels of county, city, province, and nation should be systematically implemented. The rights to hold periodic free elections and to participate in them as a citizen are inalienable.

8. Rural–Urban Equality. The two-tier household registry system must be abolished. This system favors urban residents and harms rural residents. We should establish instead a system that gives every citizen the same constitutional rights and the same freedom to choose where to live.

9. Freedom to Form Groups. The right of citizens to form groups must be guaranteed. The current system for registering nongovernment groups, which requires a group to be "approved," should be replaced by a system in which a group simply registers itself. The formation of political parties should be governed by the constitution and the laws, which means that we must abolish the special privilege of one party to monopolize power and must guarantee principles of free and fair competition among political parties.

10. Freedom to Assemble. The constitution provides that peaceful assembly, demonstration, protest, and freedom of expression are fundamental rights of a citizen. The ruling party and the government must not be permitted to subject these to illegal interference or unconstitutional obstruction.

11. Freedom of Expression. We should make freedom of speech, freedom of the press, and academic freedom universal, thereby guaranteeing that citizens can be informed and can exercise their right of political supervision. These freedoms should be upheld by a Press Law that abolishes political restrictions on the press. The provision in the current Criminal Law that refers to "the crime of incitement to subvert state power" must be abolished. We should end the practice of viewing words as crimes.

12. Freedom of Religion. We must guarantee freedom of religion and belief, and institute a separation of religion and state. There must be no governmental interference in peaceful religious activities. We should abolish any laws, regulations, or local rules that limit or suppress the religious freedom of citizens. We should abolish the current system that requires religious groups (and their places of worship) to get official approval in advance and substitute for it a system in which registry is optional and, for those who choose to register, automatic.

13. Civic Education. In our schools we should abolish political curriculums and examinations that are designed to indoctrinate students in state ideology and to instill support for the rule of one party. We should replace them with civic education that advances universal values and citizens' rights, fosters civic consciousness, and promotes civic virtues that serve society.

14. Protection of Private Property. We should establish and protect the right to private property and promote an economic system of free and fair markets. We should do away with government monopolies in commerce and industry and guarantee the freedom to start new enterprises. We should establish a Committee on State-Owned Property, reporting to the national legislature, that will monitor the transfer of state-owned enterprises to private ownership in a fair, competitive, and orderly manner. We should institute a land reform that promotes private ownership of land, guarantees the right to buy and sell land, and allows the true value of private property to be adequately reflected in the market.

15. Financial and Tax Reform. We should establish a democratically regulated and accountable system of public finance that ensures the protection of taxpayer rights and that operates through legal procedures. We need a system by which public revenues that belong to a certain level of government—central, provincial, county or local—are controlled at that level. We need major tax reform that will abolish any unfair taxes, simplify the tax system, and spread the tax burden fairly. Government officials should not be able to raise taxes, or institute new ones, without public deliberation and the approval of a democratic assembly. We should reform the ownership system in order to encourage competition among a wider variety of market participants.

16. Social Security. We should establish a fair and adequate social security system that covers all citizens and ensures basic access to education, health care, retirement security, and employment.

17. Protection of the Environment. We need to protect the natural environment and to promote development in a way that is sustainable and responsible to our descendants and to the rest of humanity. This means insisting that the state and its officials at all levels not only do what they must do to achieve these goals, but also accept the supervision and participation of nongovernmental organizations.

18. A Federated Republic. A democratic China should seek to act as a responsible major power contributing toward peace and development in the Asian Pacific region by approaching others in a spirit of equality and fairness. In Hong Kong and Macao, we should support the freedoms that already exist. With respect to Taiwan, we should declare our commitment to the principles of freedom and democracy and then, negotiating as equals and ready to compromise, seek a formula for peaceful unification. We should approach disputes in the national-minority areas of China with an open mind, seeking ways to find a workable framework within which all ethnic and religious groups can flourish. We should aim ultimately at a federation of democratic communities of China.

19. Truth in Reconciliation. We should restore the reputations of all people, including their family members, who suffered political stigma in the political campaigns of the past or who have been labeled as criminals because of their thought, speech, or faith. The state should pay reparations to these people. All political prisoners and prisoners of conscience must be released. There should be a Truth Investigation Commission charged with finding the facts about past injustices and atrocities, determining responsibility for them, upholding justice, and, on these bases, seeking social reconciliation.

China, as a major nation of the world, as one of five permanent members of the United Nations Security Council, and as a member of the UN Council on Human Rights, should be contributing to peace for humankind and progress toward human rights. Unfortunately, we stand today as the only country among the major nations that remains mired in authoritarian politics. Our political system continues to produce human rights disasters and social crises, thereby not only constricting China's own development but also limiting the progress of all of human civilization. This must change, truly it must. The democratization of Chinese politics can be put off no longer.

Accordingly, we dare to put civic spirit into practice by announcing Charter 08. We hope that our fellow citizens who feel a similar sense of crisis, responsibility, and mission, whether they are inside the government or not, and regardless of their social status, will set aside small differences to embrace the broad goals of this citizens' movement. Together we can work for major changes in Chinese society and for the rapid establishment of a free, democratic, and constitutional country. We can bring to reality the goals and ideals that our people have incessantly been seeking for more than a hundred years, and can bring a brilliant new chapter to Chinese civilization.

—Translated from the Chinese by Perry LinkPOSTSCRIPTThe planning and drafting of Charter 08 began in the late spring of 2008, but Chinese authorities were apparently unaware of it or unconcerned by it until several days before it was announced on December 10. On December 6, Wen Kejian, a writer who signed the charter, was detained in the city of Hangzhou in eastern China and questioned for about an hour. Police told Wen that Charter 08 was "different" from earlier dissident statements, and "a fairly grave matter." They said there would be a coordinated investigation in all cities and provinces to "root out the organizers," and they advised Wen to remove his name from the charter. Wen declined, telling the authorities that he saw the charter as a fundamental turning point in history.

Meanwhile, on December 8, in Shenzhen in the far south of China, police called on Zhao Dagong, a writer and signer of the charter, for a "chat." They told Zhao that the central authorities were concerned about the charter and asked if he was the organizer in the Shenzhen area.

Later on December 8, at 11 PM in Beijing, about twenty police entered the home of Zhang Zuhua, one of the charter's main drafters. A few of the police took Zhang with them to the local police station while the rest stayed and, as Zhang's wife watched, searched the home and confiscated books, notebooks, Zhang's passport, all four of the family's computers, and all of their cash and credit cards. (Later Zhang learned that his family's bank accounts, including those of both his and his wife's parents, had been emptied.) Meanwhile, at the police station, Zhang was detained for twelve hours, where he was questioned in detail about Charter 08 and the group Chinese Human Rights Defenders in which he is active.

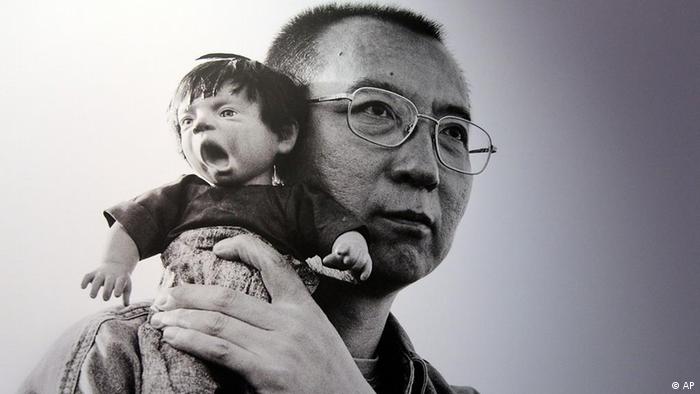

It was also late on December 8 that another of the charter's signers, the literary critic and prominent dissident Liu Xiaobo, was taken away by police. His telephone in Beijing went unanswered, as did e-mail and Skype messages sent to him. As of the present writing, he's believed to be in police custody, although the details of his detention are not known.

On the morning of December 9, Beijing lawyer Pu Zhiqiang was called in for a police "chat," and in the evening the physicist and philosopher Jiang Qisheng was called in as well. Both had signed the charter and were friends of the drafters. On December 10—the day the charter was formally announced—the Hangzhou police returned to the home of Wen Kejian, the writer they had questioned four days earlier. This time they were more threatening. They told Wen he would face severe punishment if he wrote about the charter or about Liu Xiaobo's detention. "Do you want three years in prison?" they asked. "Or four?"

On December 11 the journalist Gao Yu and the writer Liu Di, both well-known in Beijing, were interrogated about their signing of the Charter. The rights lawyer, Teng Biao, was approached by the police but declined, on principle, to meet with them. On December 12 and 13 there were reports of interrogations in many provinces—Shaanxi, Hunan, Zhejiang, Fujian, Guangdong, and others—of people who had seen the charter on the Internet, found that they agreed with it, and signed. With these people the police focused on two questions: "How did you get involved?" and "What do you know about the drafters and organizers?"

The Chinese authorities seem unaware of the irony of their actions. Their efforts to quash Charter 08 only serve to underscore China's failure to uphold the very principles that the charter advances. The charter calls for "free expression" but the regime says, by its actions, that it has once again denied such expression. The charter calls for freedom to form groups, but the nationwide police actions that have accompanied the charter's release have specifically aimed at blocking the formation of a group. The charter says "we should end the practice of viewing words as crimes," and the regime says (literally, to Wen Kejian) "we can send you to prison for these words." The charter calls for the rule of law and the regime sends police in the middle of the night to act outside the law; the charter says "police should serve as nonpartisans," and here the police are plainly partisan.

Charter 08 is signed only by citizens of the People's Republic of China who are living inside China. But Chinese living outside China are signing a letter of strong support for the charter. The eminent historian Yu Ying-shih, the astrophysicist Fang Lizhi, writers Ha Jin and Zheng Yi, and more than 160 others have so far signed.

On December 12, the Dalai Lama issued his own letter in support of the charter, writing that "a harmonious society can only come into being when there is trust among the people, freedom from fear, freedom of expression, rule of law, justice, and equality." He called on the Chinese government to release prisoners "who have been detained for exercising their freedom of expression."

—Perry Link, December 18, 2008  放大圖片

放大圖片

刘霞

刘霞 刘霞的摄影作品

刘霞的摄影作品 2010年诺贝尔和平奖颁奖仪式上特为刘晓波设置的"空椅子"

2010年诺贝尔和平奖颁奖仪式上特为刘晓波设置的"空椅子"