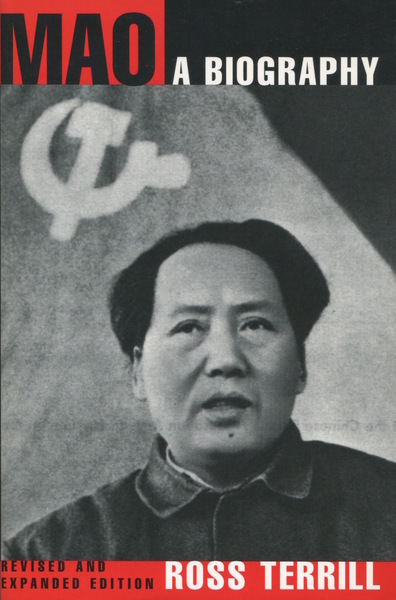

Mao: A Biography

Revised and Expanded Edition

Everyone who came in close contact with Mao was taken aback at the anarchy of his personal ways. He ate idiosyncratically. He became increasingly sexually promiscuous as he aged. He would stay up much of the night, sleep during much of the day, and at times he would postpone sleep, remaining awake for thirty-six hours or more, until tension and exhaustion overcame him.

Yet many people who met Mao came away deeply impressed by his intellectual reach, originality, style of power-within-simplicity, kindness toward low-level staff members, and the aura of respect that surrounded him at the top of Chinese politics. It would seem difficult to reconcile these two disparate views of Mao. But in a fundamental sense there was no brick wall between Mao the person and Mao the leader. This biography attempts to provide a comprehensive account of this powerful and polarizing historical figure.

About the author

Ross Terrill is a Research Associate at Harvard University's East Asian Research Center. He is the author of several books on China, including Madame Mao: The White-Boned Demon

Writing China: Nicholas Lardy, ‘Markets Over Mao’

![]()

- Courtesy of the Peterson Institute for International Economics

For the past 30 years, Nicholas Lardy has chronicled the immense changes in China’s economy and revealed some of the system’s biggest flaws. The problems include the banking sector’s bad loans in the late 1990s and the institutionalized exploitation of savers, via meager bank deposit rates, to finance economic growth. In his latest book, “Markets Over Mao,” the 68-year old senior fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics in Washington D.C., takes on China’s state-owned enterprises. His surprising conclusion: They don’t have nearly the breadth and power that China’s many critics say they do.

China Real Time recently talked with Mr. Lardy about the new book, its surprising conclusion and why he still thinks reform of state-owned firms is important. Below is an edited transcript.

You argue that China’s state-owned enterprises don’t have the power that their opponents say they do. What’s your proof?

SOEs appear to be a relatively small portion of the Chinese economy. They account for between one-third and one-quarter of GDP. But in manufacturing, SOEs only account for 20% of output. In some parts of the Chinese economy, the private sector has largely displaced state companies.

You also say the notion that China flourishes because of “state capitalism” is outmoded. Why?

State capitalism means a high degree of state ownership of production, a great deal of control over investment, a great deal of control of the banking sector and a very substantial use of industrial policy. I don’t think the term ‘state capitalism’ fits China very well because its industrial policy has been an almost complete failure.

The return on assets of state firms is plummeting. It was around 3.7% in 2013, which is less than half the cost of capital.

So how would you characterize the Chinese economy?

It’s more accurate to think of it as a market economy. The role of the state has diminished dramatically from where it was 20 to 30 years ago. When you look at the number of people employed by the state, it’s less than France as a percentage of the labor force. China’s not a pure market economy, but it’s very hard to find pure market economies these days, especially given the recent history of the financial crisis and the degree of government ownership (that resulted from actions of the U.S. and other governments to limit economic damage).

State-owned Chinese banks, though, have been characterized as ATMS for state-owned firms. Doesn’t this arrangement give Chinese SOEs a leg up over foreign and domestic competition?

A large percentage of the funds that banks lend goes to private enterprises. Banks are becoming more commercially oriented. The ability of private companies to repay loans is more than twice as great as state-owned companies, on average. (China’s banking system) is not 100% commercial, but it’s a lot more commercially oriented than observers perceive.

It is still the case, though, that the private sector is underserved. Between 2010 and 2012, private firms received, on average, 52% of the loans going to all enterprises. But they produced between two-thirds and three-quarters of China’s GDP. If they had credit proportional to their contribution to output, they would have better access to loans.

More In Writing China

- Writing China: Erwan Rambourg, 'Bling Dynasty'

- Writing China: Ko-lin Chin, 'Going Down to the Sea: Chinese Sex Workers Abroad'

- Writing China: Jack Livings, ‘The Dog’

- Writing China: James Jiann Hua To, 'Qiaowu: Extra-Territorial Policies for the Overseas Chinese'

- Writing China: ‘Chomping at the Bitcoin,’ Zennon Kapron

And you think the financial sector reforms being discussed will help private firms even more?

If you have interest-rate liberalization on deposits, lending rates will tend to go up. That will mean an increase in the amount of credit flowing to private sector firms because they can pay somewhat higher rates to banks and still be profitable. If state-owned firms are earning far less than their cost of capital, the amount that banks will want to lend to them at higher rates will probably go down.

But isn’t it clear that the Communist Party through its Organization Department exercises huge control over state-owned firms?

There is political control. The party’s Organization Department controls the top 50 firms in terms of the appointment of the three main (executives.) Provincial (officials) control a much, much larger number of appointments. This is a fundamental flaw in the governance structure. It shows how little influence their boards of directors have. The chief function of a board in any market economy is to choose who runs the company, particularly the CEO. But the Organization Department is making a serious effort to get good people.

If the control of the economy by state-owned firms is diminishing, why do you argue SOE reform is so important?

State firms’ return on assets is extremely low, relative to the cost of capital. That makes them a very big drag on China’s economic growth. They’re not that big a drag in manufacturing because state firms only account for about 10% of manufacturing investment. In the services sector, though, state firms are investing more than private firms. As China becomes a more service-dominated economy, there is an enormous opportunity (to boost economic growth by reducing state control).

In modern business services—telecom, business and leasing services, transportation– state firms are very, very dominant.

Logistics costs are relatively high. That’s in part because the logistics sector is fairly closed to foreign investment and parts of it are still very state-dominated. You’re imposing extra costs on the manufacturing sector and consumers, and making Chinese goods less competitive in global markets.

Do SOEs still have the clout to block or slow reforms?

They are an obstacle. The head of the Chinese banking association has stood up and publicly said that the association is against liberalization of deposit rates. Bankers complain that if rates are liberalized they won’t be able to make as many loans as before and that will be bad for the economy. They want more regulation to keep their protected low cost of funding. Those benefitting from (economic) distortions lobby against change.

–Edited from an interview by Bob Davis. Follow him on Twitter @bobdavis187.

Sign up for CRT’s daily newsletter to get the latest headlines by email.

Of the 95 Chinese companies on the Fortune 500 list of the world's biggest firms, some 80% are owned by the government. But in his book "Markets Over Mao", Nicholas Lardy methodically pieces together Chinese data to argue that it is the private sector, not the state, that has powered growth since the country's reform era began in 1978http://econ.st/1tFjACH