中央廣播電台-臺灣app爾文學獎得主,瑞典詩人托馬斯.特朗斯特羅默(Tomas Transtromer)所寫的「四月和沉默」,他23歲時發表首部作品《詩十七首》,轟動了整個瑞典文學界。特朗斯特羅默的創作圍繞死亡、歷史、記憶和大自然等主題,作品的特色在於獨特的隱喻,凝練的描述與言簡而意繁的組成。《詩十七首》裡第一首詩的頭一行,是他最有名的隱喻之一:「醒來就是從夢中往外跳傘」。邀訪陳文芬一起讀托馬斯.特朗斯特羅默的詩。

Thomas Tranströmer《記憶看見我》 馬悅然譯 ,台北:行人,2012

2011年諾貝爾文學獎得主的唯一回憶錄

托馬斯的寫作不存在進步與否的問題——他一出場就已達到了頂峰……——北島

對於托馬斯來說,想到「我的一生」這幾個字,就彷彿看到一顆彗星。如今年逾八十歲的他,位在彗星的尾端;而彗星的頭代表著童年和青春期,也就是決定了生命最重要特徵的階段。這本書,托馬斯回溯過往,就是要說出這段至今引領他繼續走向未來的過去。

從博物館、小學、戰爭、圖書館、初中、驅邪、拉丁文這幾個主題,我們可以看到詩人在早年生活的閱讀的興趣、憂鬱症的狀況、遭受罷凌的經驗等。這些標定生命重點的回憶片段,應當都夾帶著無比強烈的情緒,但作者寫來異常冷冽,讓這本「回憶錄」,讀來更像夢境。

本書譯者馬悅然為著名漢學家,亦為諾貝爾獎評審委員,除了讓這本托馬斯的經典著作首次完整問世,並且於附錄撰寫〈托馬斯最早的詩〉,協助讀者理解這段歷 史如何銜接上托馬斯後來的詩人生涯,文中並譯出托馬斯第一本詩集出版前所寫的九篇詩作,是理解這位大師最重要的一手資料。

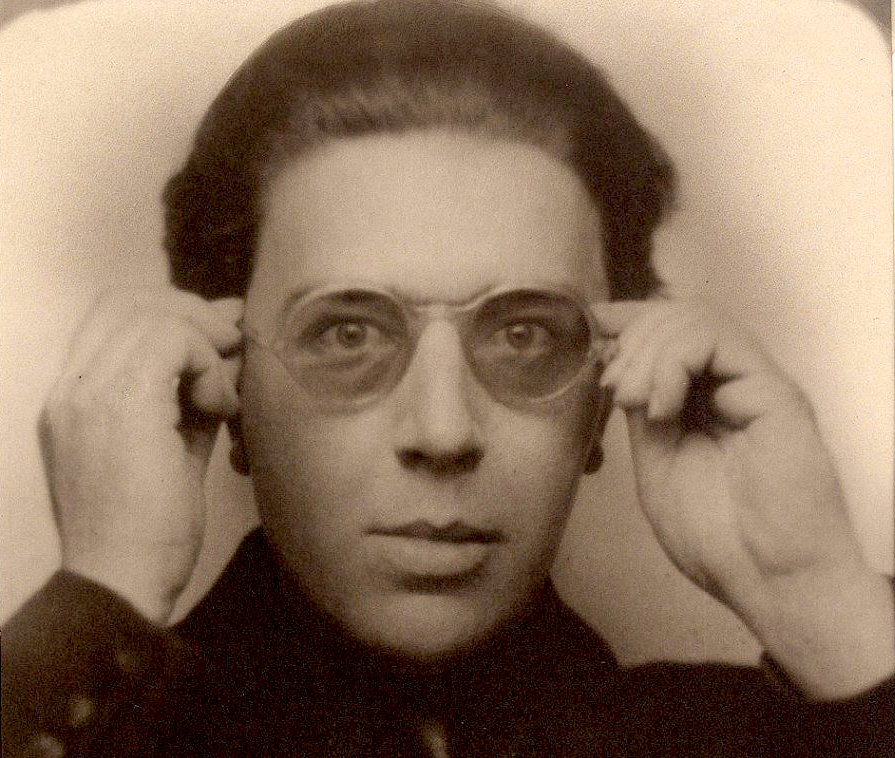

作者簡介詩人托馬斯.特朗斯特羅默 Tomas Transtromer2011年諾貝爾文學獎得主,1931年出生於瑞典,23歲時發表首部作品《詩十七首》,轟動了整個瑞典文學界。

托馬斯的創作圍繞死亡、歷史、記憶和大自然等主題,作品的特色在於獨特的隱喻,詩人最有名的隱喻之一為:「醒來就是從夢中往外跳傘」。

1990年,因中風而幾乎失去說話能力且右半身癱瘓,但他仍持續創作並用左手彈琴,1996年發表作品《悲傷的鳳尾船》,2004年再推出新作《巨大的謎語》。

2011年獲頒諾貝爾文學獎桂冠,得獎原因是:「因為透過他那簡練、透通的意象,我們以嶄新的方式體驗現實。」(“Because, through his condensed, translucent images, he gives us fresh access to reality.”)

托馬斯一共發表了十二部詩集:《詩十七首》(1954);《路上的秘密》(1954);《未完成的天》 (1962);《鐘聲與足跡》(1966);《黑暗中的視覺》(1970);《小徑》(1973);《東海》(1974);《真理的障礙》(1978); 《狂暴的廣場》(1983);《為生者與活者》(1989);《悲傷的鳳尾船》(1996)與《巨大的謎語》(2004)。詩作已被譯成六十多種語言。

目錄

記憶看見我

博物館

小學

戰爭

圖書館

初中

驅邪

拉丁文

托馬斯最早的詩

序

譯者序

馬悅然

托馬斯.特朗斯特羅默自傳性的文本《記憶看見我》,雖然出版於一九九 三年,但是肯定完成於托馬斯一九九○年中風之前。《記憶看見我》八個篇章中,托馬斯敘述他最早的零星記憶,素描他母親與他最親愛的朋友、比他大七十一歲的 外公,和小學、初中與高中同學、老師的畫像。托馬斯引領讀者進入他熱愛的博物館與圖書館,也讓讀者體會到十幾歲的他如何憎恨戰爭威脅歐洲文化的殘忍力量。 這些快樂時光的記述,也伴隨著暗淡悲慘的絕望。

托馬斯讀高中的最後兩年,開始對文學,尤其是詩歌很感興趣。那時正是瑞典現代詩的黃金時代:自由詩替代傳統的格律詩。可是托馬斯選擇了他自己的路。他閱讀羅馬詩人賀拉斯的詩時,精通了形式對詩歌的重要性。從那時起,托馬斯的詩作經常借用自古代希臘與羅馬的格律。

托馬斯高中畢業三年之後,發表了他的第一本詩集《詩十七首》(17 dikter)。他就讀高中時所寫的詩沒有選入《詩十七首》,因此我將這些詩譯成中文,列在《記憶看見我》正文之後作為參考。

內容連載 M i n n e n 記憶

「我的一生。」想到這幾個字的時候,我看見面前一道光線。仔細看,那光線真像一顆有頭有尾的彗星。彗星的頭,其最明亮的一端,是童年和青春期;彗 星的核心,其最密集的部分,是決定生命最重要特徵的幼年。我努力回憶,努力鑽進那時代。可是在這濃密的地區中移動很難,很危險,我感覺到我會接近死亡。再 往後,彗星越來越稀疏,有越來越寬的尾巴。我現在處於尾巴的後端。寫這回憶錄時,我已六十歲了。

最早的記憶多半是抓不到的。僅是敘述的複述,記憶的記憶與突然的高潮所引起的情緒。

我最早的記憶是一種感覺,一種驕傲的感覺。我剛滿三歲,有人告訴我這很重要,說我現在長大了。我躺在一間很明亮的屋子裡的床上,然後起床在地板上 走幾步,清清楚楚地意識到我正在長大了。我有一個布偶娃娃,我給她取了我所能想像的最美麗的名字:卡琳.斯品納。我對待她一點都不像一個母親對待孩子。她 更像一個朋友,或者我愛上的一位姑娘。

我們住在斯德哥爾摩的南區,我們的地址是史威登堡街(Swedenborgsgatan)三十三號(現在改名為籬笆門大街 ︹Grindsgatan︺)。爸爸還是我們的家長,可他很快要離開我們。我們的家庭是相當「現代」的—從小我對父母就用「你」這個稱呼。我的外公和外婆 住在附近,在布萊金厄街(Blekingegatan),轉彎就到。

我的外公,卡爾.黑爾默.魏斯特白格(Ca rl Helmer Westerberg),生於一八六○年。他是一位領航員,也是我最好的朋友,比我大七十一歲。奇特的是,他跟自己的外公的年齡差別是相同的,他的外公生 於一七八九年:巴黎的居民猛烈攻進巴士底,瑞典貴族反叛國王的兵變失敗了,莫札特寫著他的單簧管五重奏。人類歷史上相等的兩步,漫長的兩步,可並不太長。 我們搆得著歷史。

外公講的是十九世紀的語言。他很多的表達方式,今天的人聽起來會認為是非常過時的古怪。可是對我來說,外公講的話聽起來很自然。外公的個子不高; 他有一對雪白的八字鬚和一副相當大而稍微彎曲的鼻子—「真像個土耳其人」,他自己這麼說。他的性情是比較活躍的,他有時候會生氣。但是沒人把他的發作當作 一回事,馬上就過去了。他簡直不會嘔氣。其實他多麼願意和解的樣子,會讓人認為他是個三心二意的人。要是有人地裡談論別人的壞話,外公老會替那人辯護。

「爸爸,你當然必得同意那人是個壞蛋!」

「那我倒沒聽說過。」

父母離婚以後,媽媽跟我搬到福爾孔街(Folkunga gat an)五十七號。那座大樓容納、混雜著一群屬於底層中產階級的人。我對那大樓與其房客的回憶有一點像一場三○年代或者四○年代的電影。可愛的看門人的妻子 和她那不愛說話且身體很壯的丈夫。我欽佩那看門人的一個原因是他曾被煤氣毒害過—那暗示他英雄般地接近過很危險的機器。

除了房客,很少人出入那大樓的大門。偶然會有醉漢在樓梯上睡覺。每星期會有乞丐按我們的門鈴兒。他們嘰哩咕嚕地站在樓梯平台。媽媽給他們塗上奶油的麵包,不給他們錢。

我們住的是五層樓。最高一層。除了到頂樓的門,樓梯平台上還有四道門。一道門上寫著「娥爾克,新聞攝影師」。作為一個新聞攝影師的鄰居,真給我一種時髦的感覺。

我們透過牆壁聽得見的隔壁鄰居,是一個皮膚淺黃的中年單身漢。他在家裡工作,好像是一種用電話做生意的代理人。講電話的時候,他常常大笑,一種透過牆壁、 令人著迷的笑。另一種常常聽得見的聲音是軟木瓶塞發出砰的一聲,那個時代的啤酒瓶子沒有金屬的蓋子。這些跟興奮有關係的聲音,好像一點都不適合我偶然在電 梯裡會遇見的、那像幽靈一樣蒼白的老頭兒。後來他對別人起疑心,笑聲越來越稀少。

有一次發生暴力。我那時很小。一個鄰居喝得爛醉如泥,他妻子把門鎖了,拒絕他進來。那人大鬧,用盡全力想把門打破。我記得他大聲嚷:

「我他媽的不管你把我送到王島去!」

「王島是什麼意思?」我問媽媽。

媽媽解釋說王島是警察總局所在的地區,因此王島這個地區名聲不好。(一九三九年到一九四○年冬天,王島的一所醫院裡,我看見在芬蘭打仗受重傷的士兵以後,這個感覺更加強烈了。)

媽媽清早上班去了。她不乘車,她總是走路的。從她開始工作一直到退休那年,從首都的南區走路到首都的東北區—她在東北區的一個小學教三年級和四年級的學生。

年年就教那兩個年級的學生。她是一個專心致力的老師,也熱愛她的學生們。你也許會想像退休對她來說很不容易接受。一點都不,她感到輕鬆極了。

因為媽媽是公務員,我們家裡僱一個女僕。她主要的任務是看護我,因此應該管她叫保姆。她睡在跟廚房連起來的一間窄小的房間。這房間算是廚房的一部分,沒有包括在我們住所「兩房一廚」的設計中。

我五、六歲時,我們僱來的保姆叫安娜.麗薩。她來自瑞典最南的一省的一個小城市。我覺得她很有吸引力:一頭鬈曲的金髮,一個稍微翹起的鼻子,一種 柔軟的南方方言。她是一個非常可愛的人。我每次坐火車經過她原來住的城市的火車站,我都會體驗到一種特殊的情感,可是我從來沒有在這魔幻的地方下火車。

她是一個很有天分的姑娘,很會繪畫。她的專長是畫迪士尼卡通電影的角色。三○年代末年,我一直在繪畫。外公給我帶來那個時代所有的食品雜貨店所用 的白色包裝紙,我則在包裝紙上畫滿了我的故事。我雖然五歲時已經學會寫字,可是我嫌寫作太慢,我的想像力需要更快的表達方式。我也不耐煩好好兒地畫,我發 明一種速寫方法畫劇烈運動的身體,和缺乏細節又非常危險的戲劇。只有我自己能欣賞我畫的漫畫。

三○年代中期,我在首都的中心迷路了。媽媽跟我聽了一場給學生安排的音樂會。音樂廳的出口擠滿了人,我失去了媽媽的手,被人流帶走了。因為我很 小,媽媽看不見我。音樂廳外的廣場,天快黑了,喪失了安全感,我站在那兒。周圍雖然有人,可是他們忙於自己的事。這是我第一次經歷過死亡。

驚慌了一陣以後,我開始思考。走路回家應該是可能的,肯定是可能的。我們是坐公共汽車來的,我坐公共汽車總是跪在座位上看著窗外。王后街在外面流過去了。現在該做的是經過一站又一站地走回去。

我走的方向是對的。那段漫長的行走中,我清清楚楚地只記得一個細節。我記得我到北橋,看見橋下的水流。這兒的交通很擁擠,所以我不敢過街。我跟站 在我的旁邊的一個男人說:「這兒交通很擁擠。」他拉著我的手,領我過街。過了街,他就放開我了。我不知道他和其他陌生的成年人,怎麼會認為小孩兒一個人在 黑夜裡在首都的街上走是一件很正常的事。可就是這樣。從這裡的行走—穿過老城,洩水道和南區的街道—肯定很複雜。我靠的也許是狗和傳信鴿所帶的那種奇異的 指南針—你無論把它們放在什麼地方,它們總會找著回家的路。最後一段路我不記得了。不對,我記得我的自信心一直在增長,記得我回家的時候非常興奮。外公迎 接我。

我傷心的媽媽正在警察局探聽搜尋我的過程。外公保持他的堅強意志,很自然地迎接我。他當然很高興,但一點都沒有加油添醋。一切都很安全,很自然。

《特朗斯特羅默詩選》董繼平譯,石家莊:河北教育,2003

也是值得一讀的版本

《特朗斯特羅姆詩歌全集》作者: [瑞典] 托馬斯·特朗斯特羅姆 譯者: 李笠 成都: 四川文藝出版社, 2012-3頁數: 370 內容簡介 · · · · · ·本書是一本詩集,是2011年諾貝爾文學獎獲得者、瑞典著名詩人托馬斯·特朗斯特羅姆的詩歌全集,收錄了詩人從1954年至今創作的《17首詩》《途中的秘密》《完成一半的天空》《音色和足跡》等13部詩集近200首詩歌,囊括了特朗斯特朗姆迄今為止的所有作品,還收錄了諾貝爾文學獎授獎詞、譯者序言和作者創作於1993年的回憶文章。譯者李笠是旅居瑞典的中國詩人,曾於2001年在國內翻譯出版過《特朗斯特羅姆詩全集》,該書收錄了1999年前詩人的作品。本次出版的全新版本增錄了新作60餘首,此外,李笠還對一些舊作的中文譯文內容進行了修訂,以前有些誤譯的地方,這次已經修改過來,譯文打磨上也更為精緻。作者簡介 · · · · · ·特朗斯特羅姆(Tomas Transtromer,1931-)瑞典著名詩人。 2011年諾貝爾文學獎得主。 1954年發表詩集《17首詩》,轟動詩壇。至今共發表兩百餘首詩。 1990年患腦溢血導致右半身癱瘓後,仍堅持純詩寫作。15年來,唯一一個獲諾貝爾文學獎的詩人20年來,偏癱的身體,僅靠一隻手寫作30年來,他的詩歌影響了整整一代中國實力派詩人80年來,他堅持用只用詩歌一種文體進行創作目錄 · · · · · ·授獎詞譯者序17首詩(1954)第一部分序曲第二部分風暴夜——晨複調第三部分致梭羅的五首詩果戈理水手長的故事節與對節激奮的打坐石頭聯繫早晨與入口靜息是濺起浪花的船頭晝變第四部分悲歌尾聲... On Poetry

Versions

Tomas Transtromer’s Poems and the Art of Translation

By DAVID ORR

Published: March 9, 2012

If you’re a poet outside the Anglophone world, and you manage to win the Nobel Prize, two things are likely to happen. First, your ascendancy will be questioned by fiction critics in a major English-language news publication. Second, there will be a fair amount of pushing and shoving among your translators (if you have any), as publishers attempt to capitalize on your 15 minutes of free media attention.

Ulla Montan

Tomas Transtromer

And lo, for the Swedish poet Tomas Transtromer, it has come to pass. The questioning came from, among others, Philip Hensher for The Telegraph (in Britain) and Hephzibah Anderson for Bloomberg News, both of whom implied that real writers — Philip Roth, for instance — had been bypassed to flatter a country largely inhabited by melancholic reindeer. And when Transtromer hasn’t been doubted by fiction critics, he’s been clutched at by publishing houses. Since his Nobel moment in October, three different Transtromer books have been released (or reissued): THE DELETED WORLD: Poems (Farrar, Straus & Giroux, $13), with translations by the Scottish poet Robin Robertson; TOMAS TRANSTROMER: Selected Poems (Ecco/HarperCollins, $15.99), edited by Robert Hass; and FOR THE LIVING AND THE DEAD: Poems and a Memoir (Ecco/HarperCollins, $15.99), edited by Daniel Halpern. These books join two major collections already in print: “The Half-Finished Heaven: The Best Poems of Tomas Transtromer,” from Graywolf Press, translated by Robert Bly, and “The Great Enigma: New Collected Poems,” from New Directions, translated by Robin Fulton. So a little complaining, a glut of books: pretty typical.

But what’s unusual about Transtromer is that the most interesting debates over English versions of his work actually took place before his Nobel victory. In this case, the argument went to the heart of the translator’s function and occurred mostly in The Times Literary Supplement. The disputants were Fulton, one of Transtromer’s longest-serving translators, and Robertson, who has described his own efforts as “imitations.” Fulton accused Robertson (who doesn’t speak Swedish) of borrowing from his more faithful versions while inserting superfluous bits of Robertson’s own creation — in essence, creating poems that are neither accurate translations nor interesting departures. Fulton rolled his eyes at “the strange current fashion whereby a ‘translation’ is liable to be praised in inverse proportion to the ‘translator’s’ knowledge of the original language.” Robertson’s supporters countered that Fulton was just annoyed because Robertson was more concerned with the spirit of the poems than with getting every little kottbulle exactly right.

To understand this dispute, it’s necessary to have a sense of the poetry itself. Transtromer prefers still, pared-down arrangements that rely more on image and tone than, say, peculiarities of diction or references to local culture. The voice is typically calm yet weary, as if the lines were meant to be read after midnight, in an office from which everyone else had gone home. And his gift for metaphor is remarkable, as in the start of “Open and Closed Spaces” (in Fulton’s translation):

A man feels the world with his work like a glove.

He rests for a while at midday having laid aside

the gloves on the shelf.

They suddenly grow, spread,

and black out the whole house from inside.

The first comparison is surprising enough — work is a glove? With which we feel the world? But notice how quickly yet smoothly Transtromer extends the metaphor into even stranger territory; the gloves expand from the refuge of the house (which is implicitly the private self) to obscure everything we know and are. The poem becomes a meditation on what constitutes a prison, what could be considered a release (“ ‘Amnesty,’ runs the whisper in the grass”) and whether these might lie closer together than we realize. It ends:

Further north you can see from a summit the

endless blue carpet of pine forest

where the cloud shadows

are standing still.

No, are flying.

The clouds appear motionless but are actually flying — just as our lives move, or fail to move, in ways we only dimly understand. Open spaces may become closed, but the reverse is true as well.

Transtromer, trained as a psychologist, has always been interested in the ways our personalities obscure as much as they reveal. “Two truths approach each other,” he writes in “Preludes” (translation by May Swenson), “One comes from within, / one comes from without — and where they meet you have the chance / to catch a look at yourself.” In this context, his heavy reliance on metaphor isn’t surprising. A metaphor insists on the similarity of its tenor and vehicle, but also declares their fundamental difference: after all, the metaphor itself would be unnecessary if its components were identical. These countervailing purposes become, in Transtromer’s hands, a way of holding together what he can and can’t say. As he puts it in Fulton’s translation of “April and Silence”: “I am carried in my shadow / like a violin / in its black case.” He balances these often startling juxtapositions with simple diction and generally straightforward syntax, making the complexity of his poetry a matter of depth rather than surface. His poems are small, cool fields dissolving into dreams at their borders.

This is exactly the sort of writing that tends to do well in translation, at least in theory. The plainer a poem looks — the less it relies on extremities of form, diction or syntax — the more we assume that even a translator with no knowledge of the original language will be able to produce a reasonable match for what the poem feels like in its first incarnation.

The problem is, simple can be complicated. It’s impossible to say how much Robertson did or didn’t rely on Fulton’s translations in preparing “The Deleted World,” but it’s not too hard (if you can corral a Swedish friend, as I did) to figure out where he deviates from the originals. The changes generally make Transtromer less, well, strange and more typically “poetic.” Consider “Autumnal Archipelago (Storm),” which in Robertson’s version begins like so:

Suddenly the walker comes upon the

ancient oak: a huge

rooted elk whose hardwood antlers, wide

as this horizon, guard the stone-green

walls of the sea.

And here is Fulton’s more literal take:

Here the walker suddenly meets the giant

oak tree, like a petrified elk whose crown is

furlongs wide before the September ocean’s

murky green fortress.

Robertson forgoes the poem’s Sapphic stanza form, which seems reasonable, but he also turns the passage’s deliciously bizarre doubled metaphor (an oak tree is like an elk turned to stone) into a less jarring formulation. Similarly, in “From March 1979,” Robertson translates the line “Det vilda har inga ord” into “Wilderness has no words” when a more accurate version would be “The wild has no words” (Fulton says “The untamed . . . ”). “Wilderness” is a bunch of trees; “the wild” is another thing entirely. But perhaps the least successful adjustment is in “Calling Home”:

Our phonecall spilled out into the dark

and glittered between the countryside

and the town

like the mess of a knife-fight.

There’s no fight, with knives or otherwise, in the original — Transtromer’s speaker “slept uneasily” after the call home, but the cause of his unease is unresolved. Again, the poem seems simplified.

That said, some of Robertson’s alterations do a fine job of conveying a poem’s spirit. Rather than using the literal “shriveled” to describe a sail, he says it’s “grey with mildew.” Rather than telling us that “dead bodies” are smuggled into “a silent world,” he says “the dead” are so transported. In general, while one can quibble about Robertson’s book, “The Deleted World” is pleasurable whether or not it’s a good translation of Transtromer.

Is that enough? In some ways, certainly — we read poetry for entertainment, not nutritional value. But translating a poem is like covering a song. We can savor the liberties someone is taking with, say, “Gin and Juice” in a way we couldn’t understand similar variations on songs written by Martians. And Transtromer, however popular he is among poets, remains largely unknown to readers eager to see work from the new Nobel laureate. In this instance, even a sincere imitation probably isn’t the most helpful form of flattery.

托馬斯.特朗斯特羅默 詩二首譯◎馬悅然孤獨

I2月的一天晚上 我在這裡 接近死亡。汽車在冰上 斜滑到路的對面。 從對面來的汽車──它們的前燈──靠近了。我的名字 我的女兒 我的工作掙脫了束縛 默默地留在愈來愈遠的後頭。 我是無名的,像一個在校園上 被敵人圍繞的 男孩。從對面來的汽車 有巨大的前燈。它們照射在我身上當我在蛋清一樣黏的透明的恐懼裡,緊握著駕駛盤。秒鐘加長了──甚至容納你的身體──長得像醫院大樓一樣高大。你幾乎可以停一下,在你被壓碎前一片刻出一口氣。忽然 輪胎抓牢路面: 一粒幫助的沙子或者一陣奇妙的風 叫汽車掙脫了束縛,輕快地爬過道路。一個突出來的電線桿 啪的一聲 折斷了,在黑暗裡 飛走了。等到靜止。我繫著安全帶 坐著那兒,看見有人 在飛雪裡 走過來,想看我怎了。II我在鄰省凍冰的田野上走了很久。一個人都不見了。在地球其他地區永久的擁擠中有人出生,生活,死亡。總是給人看到的,總是生活在一群眼睛中一定會產出一種特殊的表情。塗上泥巴的臉。喃喃的聲音起伏當他們彼此分攤天空,影子,沙粒。我必須孤獨早晨十分鐘晚上十分鐘。沒有規畫。大家在大家的面前排隊。很多。一個。

自1979年3月

聽膩了所有獻話語的人,話語,非語言。我逃到雪蓋的海島。狂野沒有話語。四面八方空白的紙頁!我雪中忽遇鹿蹄之蹤跡。語言,非話語。■編按:去年12月7日的諾貝爾獎文學演講會,改為朗讀音樂會。托馬斯.特朗斯特羅默指定〈孤獨〉做為五種語文譯本朗讀。漢學家馬悅然為此將詩作譯為中文。〈自1979年3月〉為詩人名作,其妻子莫妮卡在諾獎晚宴代謝答辭時,以這首詩做為回答。

特朗斯特羅默在日本◎林水福今年諾貝爾文學獎,日本全部摃龜。村上春樹是日本人的期待之一,但是,機率多少?沒人知道。從過去諾貝爾文學獎得主的文學屬性來看,村上的通俗與大眾品味,有人擔心會是阻礙。村上將來如果真能獲得,至少宣告日本新文學觀時代的來臨。特 朗斯特羅默的翻譯作品,到他獲諾貝爾文學獎為止,在日本只有一本。那是住在斯德哥爾摩的翻譯家Eiko duke翻譯的,由專門出版詩集和詩論的思潮社於1999年發行。書名(悲傷的鳳尾船),初版印行三百本,一般人大概無緣見識到;預 定11月再版。特朗斯特羅默從二十幾歲起就對俳句的定型詩感興趣,稱正岡子規(1867-1902,提出俳諧革新說,主張將俳諧的「發句」 獨立出來,稱「俳句」,後人沿用至今。)為「在死亡的木板,以生命的粉筆書寫的詩人」。1990年因腦中風,造成右半身不遂和失語症,對表現極為精煉的俳 句更加傾倒。譯者Eiko稱1996年出版的《悲傷的鳳尾船》,「直截表現出與疾病共存的詩人的閉塞感和苦惱,在沉重的悲傷基調下,透明的幻想飄蕩在生與 死的境界。」這本詩集出現所謂的「俳句詩」如:「幾根高壓線/在結凍的國度張弦/音樂圈的北方之涯」;「蘭花的窗邊/滑行而過的油船/月圓的晚上」;「一 對紅蜻蜓/以緊緊糾纏之姿/搖曳著飛走」。特朗斯特羅默的俳句詩,基本上採五.七.五的俳句詩型,以三行詩的方式呈現,而複數的俳句詩如連 詩般的組合,創造出豐富的意象。2004年出版的詩集《大大的謎題》是詩人渾身努力的結晶,收入四十五篇俳句詩。2005年9月號《現代詩手帖》刊登了 Eiko翻譯、介紹,由十八篇詩組成如默示錄的〈鷲之涯〉。其中一篇:「大海變成牆壁/聽到海鷗的叫聲──/是給我們的信號」。歷經311大海嘯洗禮的日本人對這一首詩感觸特別深。如上述,目前日本只有一本特朗斯特羅默的詩集,和《現代詩手帖》的翻譯,可說相當少。這次他的得獎,在日本可能掀起一波翻譯和研究的熱潮,尤其是俳句詩方面。 ●

----

Haiku by Tomas Tranströmer

IA lamasery

with hanging gardens.

Battle pictures.

Thoughts stand unmoving

like the mosaic tiles

in the palace yard.

Up along the slopes

under the sun – the goats

were grazing on fire.

On the balcony

standing in a cage of sunbeams –

like a rainbow.

Humming in the mist.

There, a fishing-boat out far –

trophy on the waters.

IICool shagginess of pines

on the selfsame tragic fen.

Always and always.

Carried by darkness.

I met an immense shadow

in a pair of eyes.

These milestones

have set out on a journey.

Hear the wood-dove’s voice.

IIIResting on a shelf

in the library of fools

the sermon-book, untouched.

My happiness swelled

and the frogs sang in the bogs

of Pomerania.

He’s writing, writing…

The canals brimmed with glue.

The barge across the Styx.

Go quiet as rain,

meet the whispering leaves.

Hear the Kremlin bell.

IVThe ceiling rent open

and the dead one sees me.

This face.

Something has happened.

The moon lit up the room.

God knew about it.

Hear the sighing rain.

I whisper a secret, to reach

all the way in there.

A scene on the platform.

What a strange calm –

the inner voice.

VThe sea is a wall.

I hear the gulls crying –

they’re waving to us.

God’s wind at my back.

The shot which comes without sound –

a dream all-too-long.

Ash-colored silence.

The blue giant passes.

Cool breeze from the sea.

I have been there –

and on a whitewashed wall

the flies are gathering.

Birdmen.

The apple trees in blossom.

The big enigma.

Translated by Robert Archambeau and Lars-Håkan Svensson瑞典皇家科學院在周四(10月6日)宣布將2011年度諾貝爾文學獎授予詩人托馬斯·特蘭斯特勒默(Thomas Tranströmer)。瑞典皇家科學院在周四(10月6日)宣布將2011年度諾貝爾文學獎授予瑞典詩人托馬斯·特蘭斯特勒默(Thomas Tranströmer)。現年80歲的特蘭斯特勒默的詩歌作品被評為會稱為"形象具體""比喻恰當",為讀者提供了一個"通往現實的新入口"。特蘭斯特勒默是國際文壇很有地位的詩人之一。他的詩集共收集了近100部作品,譯成近50種文字出版。特蘭斯特勒默出身於一個瑞典斯德哥爾摩普通家庭,父親是記者,母親是教師。他本人在上世紀50年代在斯德哥爾摩大學就讀心理學、文學和宗教史。特蘭斯特勒默發表處女作是在1954年。不過他從未中斷過從事心理諮詢師的工作,在一個青少年拘留所做心理專家,直到1990年因一次嚴重的腦溢血而離開了工作崗位。身體稍微恢復後,他又在許多政府部門裡兼職作心理諮詢師。隨著上世紀68學運席捲歐美,特蘭斯特勒默失去了不少讀者。有人批評他的詩歌過於樂觀,缺少揭露矛盾的勇氣,與當時的政治和社會討論議題完全不相吻合。特蘭斯特勒默對此的回應是,他的作品不是以意識形態為根源的,而是著眼未來願景。自從1990年患過一次嚴重腦溢血後,特蘭斯特勒默行動和言語表達能力都受到影響。他和妻子莫妮卡生活在斯德哥爾摩,很少在公眾場合露面。 1993年,在妻子的協助下特蘭斯特勒默出版了回憶錄《記憶看見我》。接下來的許多年,特蘭斯特羅默也沒有停止寫作,出版了多本詩集。新闻报道 | 2011.10.06

瑞典诗人获本年度诺贝尔文学奖

瑞典皇家科学院在周四(10月6日)宣布将2011年度诺贝尔文学奖授予诗人托马斯·特兰斯特勒默(Thomas Tranströmer)。

瑞典皇家科学院在周四(10月6日)宣布将2011年度诺贝尔文学奖授予瑞典诗人托马斯·特兰斯特勒默(Thomas Tranströmer)。现年80岁的特兰斯特勒默的诗歌作品被评为会称为"形象具体""比喻恰当",为读者提供了一个"通往现实的新入口"。

特兰斯特勒默是国际文坛很有地位的诗人之一。他的诗集共收集了近100部作品,译成近50种文字出版。

特兰斯特勒默出身于一个瑞典斯德哥尔摩普通家庭,父亲是记者,母亲是教师。他本人在上世纪50年代在斯德哥尔摩大学就读心理学、文学和宗教史。

特兰斯特勒默发表处女作是在1954年。不过他从未中断过从事心理咨询师的工作,在一个青少年拘留所做心理专家,直到1990年因一次严重的脑溢血而离开了工作岗位。身体稍微恢复后,他又在许多政府部门里兼职作心理咨询师。

随着上世纪68学运席卷欧美,特兰斯特勒默失去了不少读者。有人批评他的诗歌过于乐观,缺少揭露矛盾的勇气,与当时的政治和社会讨论议题完全不相吻合。特兰斯特勒默对此的回应是,他的作品不是以意识形态为根源的,而是着眼未来愿景。

自从1990年患过一次严重脑溢血后,特兰斯特勒默行动和言语表达能力都受到影响。他和妻子莫妮卡生活在斯德哥尔摩,很少在公众场合露面。1993年,在妻子的协助下特兰斯特勒默出版了回忆录《记忆看见我》。接下来的许多年,特兰斯特罗默也没有停止写作,出版了多本诗集。

作者: Thomas Borchert 编译:谢菲

责编:乐然

Literature | 06.10.2011

'Tranströmer shows one can survive as a poet'

The first Swede to garner the Nobel Prize in Literature in 30 years, speech-impaired poet Tomas Tranströmer has his compatriots buzzing over the honor bestowed to him. One Swedish critic says the award is long-deserved.

The real question is, why didn't they do it before? He's been at the top of the list for many, many years. He's a well-known poet, not only in Sweden, but also abroad. He's been translated into many, many languages and he is held in great esteem all over the world - at least, in the world of poetry.

![Tranströmer standing in a doorway surrounded by books]() Some have called him a poetic master 'of the mysteries of the human mind'This is the first time in more than three decades the Nobel Prize in Literature has been given to a native of Sweden. What does it mean to the Swedish people? And what does it mean for literature?

Some have called him a poetic master 'of the mysteries of the human mind'This is the first time in more than three decades the Nobel Prize in Literature has been given to a native of Sweden. What does it mean to the Swedish people? And what does it mean for literature? I think there is one reason [the award committee] hestitated for a long time - because the prize was awarded to Swedish authors 40 years ago and there was a major discussion for some time after that and a lot of criticism. The Swedish Academy was criticized back then for awarding minor Swedish authors the award.

It's a peculiar debate, really, because I can't think of any other prize in a country that doesn't go very often to compatriots of that country. Tranströmer has been talked about for a long time and it's good that he's finally received it.

Swedes have never really had the prize very often. It's usually awarded to international authors. But of course, it's usually been awarded to white, male authors from the Western world - very few Africans and very few Asians.

![Book cover]() His works have been translated into countless languages

His works have been translated into countless languagesBut if there's someone who was due to get the prize now, it was definitely Tranströmer. There's no discussion about that.

Why do you say that? What is Tranströmer's defining characteristic as a lyricist? - his poetic signature?He's been writing poetry for 50 years and he's proven one can survive as a poet. New generations discover him and he's a poet who writes in a way that on the surface is very simple and accessible for anybody. Even those who normally don't read poetry can read Tranströmer. At the same time, he's very complex and very precise in his imagery. He tries to find one image for a feeling or a situation. He looks at the world in a way I would imagine the dead would look at the world - with all their knowledge, condensed into one image.

That's one big reason why he has survived. But also, because he is a poet of modernity. He travels around in his poetry; he goes by car and by train, and by bus. It's a world that is recognizable, and at the same time, you feel you see this world for the first time - because he's found the perfect expression or the perfect image for what he sees and hears. There's a lot of music in his poetry as well.

Tranströmer has been publishing since the 1950s. How much of the collective Swedish conscience do you think is reflected in his work? Is there a collective Swedish conscience? [Laughs.] I wonder. As I said, he's found expressions for modern life in Sweden.

But at the same time, he's a very existentialist poet. There's a lot of sorrow and death and darkness in his poetry, not only in his late poetry, where it's so obvious, but right from the start. But also light, of course.

![Swedish landscape]() Painting the world through words, here, in Sweden

Painting the world through words, here, in SwedenSomebody once said that it's like in the Bible when God has to show us all the animals and give them their names. In a way, Tomas Tranströmer sort of does that in his poetry. He creates the world anew through language.

The poet was afflicted with a loss of speech and partial paralysis following a stroke two decades ago. How much do you think that event and his need for a helping hand affected his writing?A lot. A mean, he's written little since then. The last big, really important collection - "The Sorrow Gondola," inspired by a piano piece by Franz Liszt - consisted of poems written both before the stroke, and also some were written after the stroke. There's hardly any difference between them and I can imagine that those written after the stroke already existed in some form beforehand.

After that, he has written one more collection of poetry where you can see that he's lost some of the touch. I mean, he still writes, but we don't really know how. He writes with the help of his wife, who interprets them. She writes things down, and he says whether or not that's what he meant. Of course it's affected him - after all, he's now aphasic. He can say "good" and "very good" and that's it.

What significance does it have that this year's Nobel Prize was awarded to a poet and not a novelist? Is our abbreviated take of the world nowadays, due to e-mails, text messages and the ever more hectic pace of life, reflected in that choice? Poetry has fewer words, yet more poignant images after all …I think it was Wislawa Szymborska who was the last poet to be awarded the Nobel Prize [in 1996]. Perhaps I've missed someone, but it's been a very long time since a poet has been awarded the prize. I really don't know how the discussion goes in the Swedish Academy. They don't tell you now. They only tell you after 50 years. The last 10 prizes - I've been so surprised! Every time!

On that note, in the run-up to the announcement, literary critics considered possible candidates to be everyone from Syrian poet Adonis, to poetic music legend Bob Dylan to Japanese writer Haruki Murakami. What do you think personally about the choice?![Tranströmer celebrated his 80th birthday this past April]() Tranströmer celebrated his 80th birthday this past April

Tranströmer celebrated his 80th birthday this past April I don't think Bob Dylan will ever get the prize! [Laughs.] I mean, I think he's a great poet, but I think the academy thinks he's in the popular sphere. Adonis has been on the agenda for quite some time and I haven't given up hope about him yet. But this year, I don't think they would ever have given it to him.

Because he's Syrian, it would have been interpreted by the press in a political way and I think the academy wants to avoid that. I mean, the election of a Nobel Prize winner is a very long and complicated procedure, and the ones who are on the committee for the literary prize - they differ very much in opinions, and they all have their favorites.

There's always lots of speculation about the winners every year, and rarely are they accurate. I'm almost always surprised myself.

Is there anything else you'd like to add?Just that I'm very happy, and almost relieved that Tranströmer finally got the prize. It was almost too late, and it nearly drove tears to my eyes.

Interview: Louisa Schaefer

Editor: Stuart Tiffen

Tomas Gösta Tranströmer (born 15 April 1931) is a

Swedish writer, poet and translator, whose poetry has been translated into over 60 languages.

[1] He is the recipient of the 2011

Nobel Prize for Literature"because, through his condensed, translucent images, he gives us fresh access to reality".

[2] Tranströmer is acclaimed as one of the most important Scandinavian writers since World War II. Critics have praised Tranströmer’s poems for their accessibility, even in translation; his descriptions of the long Swedish winters, the rhythm of the seasons and the palpable, atmospheric beauty of nature.

[1]Tranströmer was born in Stockholm in 1931 and raised by his mother, a schoolteacher, following her divorce from his father.

[2][3] He received his secondary education at the Södra Latin School in Stockholm, where he began writing poetry. In addition to selected journal publications, his first collection of poems,

17 dikter(Seventeen Poems), was published in 1954. He continued his education at

Stockholm University, graduating as a psychologist in 1956 with additional studies history, religion, and literature.

[2] Between 1960 and 1966, Tranströmer split his time between working as a psychologist at the Roxtuna center for juvenile offenders and writing poetry.

[2]During the 1950s, Tranströmer became close friends with poet

Robert Bly. The two corresponded frequently, and Bly would translate Tranströmer's poems into English.

Bonniers, Tranströmer's publisher, released

Air Mail, a work comprising of Tranströmer and Bly's mail, in 2001.

[2] The Syrian poet

Adunis helped spread Tranströmer's fame in the Arab World, accompanying him on readings.

[4]Tranströmer went to

Bhopal immediately after the

gas tragedy in 1984, and alongside Indian poets such as

K. Satchidanandan, took part in a poetry reading session outside.

[5]Tranströmer suffered a

stroke in 1990 that left him partially paralyzed and unable to speak; however, he would continue to write and publish poetry through the early 2000s. His last original work,

The Great Enigma, was published in 2004.

In addition to his writing, Tranströmer is also a piano player, something he has been able to continue after his stroke, albeit with one hand.

[3]Tranströmer is considered to be one of the "most influential Scandinavian poet[s] of recent decades".

[2] Tranströmer has published 15 collected works over his career, which has been translated into over 60 languages.

[2] An English translation by

Robin Fulton of his entire body of work,

New Collected Poems, was published in the UK in 1987 and expanded in 1997. Following the publication of

Den stora gåtan(The Great Enigma), Fulton's edition was further expanded into

The Great Enigma: New Collected Poems, published in the US in 2006 and as an updated edition of

New Collected Poems[6] in the UK in 2011. He published a short autobiography,

Minnena ser mig(Memories look at me), in 1993.

Other poets, especially in the "political" 1970's, accused Tranströmer of being apart from his tradition and not including political issues in his poems and novels. His work, though, lies within and further develops the

Modernist and

Expressionist/

Surrealist language of 20th century poetry; his clear, seemingly simple pictures from everyday life and nature in particular reveals a mystic insight to the universal aspects of the human mind.

A poem of his was read at

Anna Lindh's memorial service in 2003.

[7]Tranströmer was awarded the

Nobel Prize in Literature in 2011.

[2][3] He was the 108th winner of the award and the first Swede to win since 1974.

[8][7][9]> Tranströmer had been considered a perennial frontrunner for the award in years past, with reporters waiting near his residence on the day of the announcement in years prior.

[10] The Nobel Committee cited that Tranströmer's work created "condensed, translucent images" that "gives us fresh access to reality."

[2]Tranströmer and his wife Monica appeared at a brief news conference. They were sitting in front of their television waiting the announcement of the winner. Tranströmer managed to say "Very good, very good" when asked what it was like to have won.

[10] Permanent secretary of the Swedish Academy

Peter Englund said, "He's been writing poetry since 1951 when he made his debut. And has quite a small production, really. He's writing about big questions. He's writing about death, he's writing about history and memory, and nature."

[11]Prime Minister of SwedenFredrik Reinfeldt said he was ”happy and proud” at the news of Tranströmer's achievement.

[12][13]Tranströmer's other awards include the

Neustadt International Prize for Literature, the

Övralid Prize, the

Petrarca-Preis in Germany, the Golden Wreath of the

Struga Poetry Evenings and the Swedish Award from International Poetry Forum. In 2007, Tranströmer received a special Lifetime Recognition Award given by the trustees of the Griffin Trust for Excellence in Poetry, which also awards the annual

Griffin Poetry Prize.

[edit]Awards and honors

[edit]Swedish collections

- 17 dikter (17 Poems) 1954; Bonniers, 1965

- Hemligheter på vägen (Secrets on the Way), Bonnier, 1958

- Den halvfärdiga himlen (The Half-Finished Heaven), Bonnier, 1962

- Klanger och spår (Windows and Stones), Bonnier, 1966

- Mörkerseende (Night Vision), Författarförlaget, 1970

- Stigar (Paths), Författarförlaget, 1973, ISBN 9789170541100

- Östersjöar (Baltics), Bonnier, 1974

- Sanningsbarriären (The Truth Barrier), Bonnier, 1978, ISBN 9789100436841

- Det vilda torget (The Wild Square) Bonnier, 1983, ISBN 9789100460488

- För levande och döda (For the Living and the Dead), Bonnier, 1991

- Sorgegondolen (The Sorrow Gondola), Bonnier, 1996, ISBN 9789100562328

- Den stora gåtan (The Big Riddle), Bonnier, 2004, ISBN 9789100103101

- Galleriet: Reflected in Vecka nr.II (2007) – an artist book by Modhir Ahmed

[edit]Selected books in English translation

- 20 Poems tr. Robert Bly (Seventies Press, 1970)[14]

- Windows and Stones tr. May Swenson& Leif Sjoberg, University of Pittsburgh Press, 1972, ISBN 9780822932413

- Baltics tr. Samuel Charters, Oyez, Berkeley, 1975; Oasis Books, 1980, ISBN 9780903375511

- Selected Poems, translator Robin Fulton, Ardis Publishers, 1981, ISBN 9780882334622

- Collected Poems, Translator Robin Fulton, Bloodaxe Books, 1987, ISBN 9781852240233

- Tomas Tranströmer: Selected Poems, 1954–1986, Editor Robert Hass, Publisher Ecco Press, 1987 ISBN 9780880011136

- Sorrow Gondola: Sorgegondolen tr. Robin Fulton, Dufour Editions, 1994, ISBN 9781873790489; Dufour Editions, Incorporated, 1997, ISBN 9780802390707

- New Collected Poems tr. Robin Fulton, Bloodaxe Books, 1997, ISBN 9781852244132; Bloodaxe Books, 2011

- Selected Poems Transtromer, Translator May Swenson, Eric Sellin, HarperCollins, 1999, ISBN 9780880014038

- The Half-Finished Heaven tr. Robert Bly, Graywolf Press, 2001, ISBN 9781555973513

- The Deleted World tr. Robin RobertsonEnitharmon Press, 2006, ISBN 9781904634485; Enitharmon Press, 2006, ISBN 9781904634515

- The Great Enigma: New Collected Poems. Translator Robin Fulton. New Directions. 2006. ISBN9780811216722.

- The Sorrow Gondola tr. Michael McGriff and Mikaela Grassl, Green Integer, 2010, ISBN 9781933382449

- The Deleted World tr. Robin RobertsonFarrar, Straus and Giroux, 2011

[edit]References

[edit]External links

![「 In a poignant essay, renowned neurologist @[212505698805486:274:Oliver Sacks] reveals he has an incurable cancer: http://cnn.it/1Acnfdb 」](http://fbcdn-sphotos-e-a.akamaihd.net/hphotos-ak-xpf1/t31.0-8/p403x403/10629454_10153373658666509_4647708670238208587_o.jpg)

Some have called him a poetic master 'of the mysteries of the human mind'

Some have called him a poetic master 'of the mysteries of the human mind'

Sony Corp.'s new Reader device will come with Internet connections. (The Asahi Shimbun)

Sony Corp.'s new Reader device will come with Internet connections. (The Asahi Shimbun)

This, of course, is fiction not fact. But the challenge to the status quo from men like Cromwell was real enough. In his book, theWealth and Poverty of Nations, David Landes argues that the challenge to the Vatican from the new religion was a major influence. It was the dawning of a more secular age.

“The Protestant Reformation changed the rules. It gave a big boost to literacy, spawned dissents and heresies, and promoted the scepticism and refusal of authority that is at the heart of scientific endeavour. The Catholic countries, instead of meeting the challenge, responded by closure and censure.”

Northern and southern Europe started to go their own ways in the 16th century. They had different beliefs, different ways of doing things, different cultures. Half a millennium later this gulf has yet to be bridged: witness the strong sense of protestantism that informs Germany’s attitude towards Greece.

Landes says there were two special characteristics of Protestantism that support the claim that it was crucial in the rise of capitalism. One was the emphasis on the need to read, for girls as well as boys. He says that while good protestants were expected to know how to read the holy scriptures for themselves, catholics were explicitly discouraged from reading the bible.

But these were not the only changes happening. The voyages of discovery by Columbus and Magellan meant the known world was expanding. It was an era of globalisation, with new products available for import and fresh markets opening up.

Cromwell is part of this world. He has travelled widely in Europe. He has contacts in Antwerp, then a more important port than London. He is a man of the world with cosmopolitan views. He speaks foreign languages and is keen to add Polish to the list. He would not be a Ukip supporter.

The problems of the wool trader Wykys in Wolf Hall look suspiciously like a metaphor for the weaknesses of the UK economy in 2015. Presiding over a failing business, Wykys has got the wrong products, the wrong people working for him and is selling his goods in the wrong markets. “Latterly, Wykys had grown tired, let the business slide. He was still sending broadcloth to the north German market, when – in his opinion, with wool so long in the fleece these days, and good broadcloth hard to weave – he ought to be getting into kerseys, lighter cloth like that, exporting through Antwerp to Italy.”

In good company doctor fashion, Cromwell decides he can turn the business around. He takes a look at the stock, casts his eyes over the account, then fires the chief clerk and trains up a junior to take his place. “People are always the key, and if you look them in the face you can be pretty sure if they’re honest and up to the job.” Today we would say that he understood the importance of human capital.

Once he had made Henry supreme over the Church of England and disposed of Anne Boleyn, he set to work on the Dissolution of the Monasteries.