↧

北野武: 菊次郎與佐紀; 無限 Infinity

↧

鄭清文《現代英雄》

↧

↧

文化類同與文化利用 Jonathan Spence;Horace Walpole 書信選

Jonathan Spence.史景遷北大講演錄《文化類同與文化利用--世界文化總體對話中的中國形象》(Culture Equivalence and Culture Use ),廖世奇、彭小樵譯,北京大學出版社,1990年2月1版;1997年5月2版。

這是一本很難得的書

不過出版商沒說明許多細節

譬如說 什麼時候演講

根據講稿或錄音整理 或合用

沒有編索引

加一張隆溪撰文當附錄 (非法 又很不禮貌地):《非我的神話》--hc案 這篇有翻譯錯誤 譬如說 logographic 翻譯成"邏輯象形式的" 這 logo 可以想成現在商業的 logo 是類似"表意圖形式"

有趣的是 引文為第357頁 第3版為376頁

我們看Radio 4 - Reith Lectures 2008: Chinese Vistas

只四講 本書卻有8講 每講還有些文本討論 所以我猜這可能是3小時的演講

此兩講稍微有從重複 譬如說 對 Goldsmith的引文 reason out等

問題是BBC的演講引文在原書中查不到

我陸續利用之

話說大才子Horace Walpole (1717-1797) 撰印Hieroglyphic Tales: (1785 日本人稱為象形文字譚第一版在自家 Strawberry Hill的印刷場只印六份):我千辛萬苦找到:第五則故事:TALE V.Mi Li. A Chinese Fairy Tale.

http://www.gutenberg.org/files/14098/14098-h/14098-h.htm

Mi Li, prince of 除非娶一名字必須與其父的領地同名得公主,否則將是世界上最不快活的。

這故事末段很有名:

Running almost breathless up to lady Ailesbury, and seizing miss Campbell's hand—he cried, Who she? who she? Lady Ailesbury screamed, the young maiden squalled, the general, cool but offended, rushed between them, and if a prince could be collared, would have collared him—Mi Li kept fast hold with one arm, but pointing to his prize with the other, and with the most eager and supplicating looks intreating for an answer, continued to exclaim, Who she? who she? 【錢鍾書說這是這是英國人第一次讓中國人講不完全準確的英文】The general perceiving by his accent and manner that he was a foreigner, and rather tempted to laugh than be angry, replied with civil scorn, Why she is miss Caroline Campbell, daughter of lord William Campbell, his majesty's late governor of Carolina—Oh, Hih! I now recollect thy words! cried Mi Li—And so she became princess of China

***

"[Horace Walpole] prattles on for our entertainment, ultimately more kindly and generous than malevolent. He reaches out his bony crippled hands across the centuries, and smiles his knowing smile, and welcomes in his paying customers."

-- Novelist Margaret Drabble on Everyman's Library's new HORACE WALPOLE: SELECTED LETTERS, Edited by Stephen Clarke in the Times Literary Supplement

-- Novelist Margaret Drabble on Everyman's Library's new HORACE WALPOLE: SELECTED LETTERS, Edited by Stephen Clarke in the Times Literary Supplement

↧

略讀《法國浪漫主義時期的音樂與文學》Hector Berlioz『柏遼茲回憶錄 』

略讀《法國浪漫主義時期的音 樂與文學》

《法國浪漫主義時期的音樂與文學》 溫永紅譯,天津,

有人說:「《法國浪漫主義時期的音 樂與文學》

譬如說與本書類似的

La musique et les lettres en France au temps du Wagnerisme

L Guichard - 1963 - Paris: Presses Universitaires de France

L Guichard - 1963 - Paris: Presses Universitaires de France

-------

這本書的翻譯網路上有點資料: 2003年的「中央音樂學院音樂學研究所」:

「《法國浪漫主義時期的音樂和文 學》是法國作家雷翁·

影響作品的創作形式和思想內涵。

該書由我院青年教師溫永紅翻譯,是我所2000年 度的所立翻譯課

我們可以知道一本書的翻譯和出版 (包括取得法國外交部的補助),

「書中對法國大革命至 1850年浪漫主義時期的音樂、文學氛圍,

「本書的作者閱讀了 1789至1850年間有關文學與音樂的大量史料【hc案:

」

作者總結相當悲觀:現代人只喜歡德國浪漫主義的音樂,很少人會聽 法國浪漫主義時期的音樂了。不過,

「音樂、藝術、哲學、科學和文學」這主題,從有史以來一直很豐富。在1894年,象徴主義詩人Stephane Mallarme (1842-1898)應邀英國兩大名校演講,主題為「音樂與文學」。

法國浪漫主義古典音樂的奠基人 Hector Berlioz(1803-1869)有專章,本書各章都提到他。我注意到本書引的『柏遼茲回憶錄第二章』所提的拉丁詩,本書與『柏遼茲回憶錄』(北京:東方,2000)都沒譯出,其實北京大學故楊先生都有翻譯可參考。或許,

“Life when one first arrives is a continual mortification as one's romantic illusions are successively shattered and the musical treasure-house of one's imagination crumbles before the hopelessness of the reality. Every day fresh experiences bring fresh disappointments.”

―from THE MEMOIRS OF HECTOR BERLIOZ (1865) by Hector Berlioz

Hector Berlioz’ (1803-69) autobiography is both an account of his important place in the rise of the Romantic movement and a personal testament. He tells the story of his liaison with Harriet Smithson, and his even more passionate affairs of the mind with Shakespeare, Scott, and Byron. Familiar with all the great figures of the age, Berlioz paints brilliant portraits of Liszt, Wagner, Balzac, Weber, and Rossini, among others. And through Berlioz’s intimate and detailed self-revelation, there emerges a profoundly sympathetic and attractive man, driven, finally, by his overwhelming creative urges to a position of lonely eminence. For this new Everyman’s edition of The Memoirs, the translator–the composer’s most admired biographer–has completely revised the text and the extensive notes to take into account the latest research. READ more here: https://www.penguinrandomhouse.com/…/the-memoirs-of-hector…/

Today we wish a very happy birthday to French composer HectorBerlioz, born on this day in 1803!

Berlioz is best known for his "Symphonie fantastique,""Grande messe des morts" (Requiem), and "La damnation de Faust." The #Requiem is scored for a large orchestra, four brass choirs, and a chorus (more than 400 performers!).

On opening night of his first season as Music Director of the New York Philharmonic, Leonard Bernstein conducted Berlioz's "Roman Carnival Overture" as a surprise addition to the October 2, 1958 program.

In his Young People's Concert entitled "Berlioz Takes a Trip," originally broadcasted by CBS on May 25, 1969, Bernstein discusses what he describes as "the first psychedelic symphony", "La Symphonie Fantastique".

****'Music is a whole world'

It took Elliott Carter almost 50 years to find himself as a composer. Now the 97-year-old is one of the greatest of modernists - as even his fellow Americans are beginning to agree. He talks to Andrew Clements

Tuesday January 3, 2006

The Guardian

|  Elliott Carter in 1973. Photograph: Henry Grossman/Getty/TimeLife |

Elliott Carter is more than one of the most important composers of our time; he remains a vital link with a long-gone musical era. At the age of 97, and still composing (currently he's working on a song cycle scheduled for performance next autumn), he has been involved with new music on both sides of the Atlantic for nearly 80 years. "I've been in the middle of this all through my life," he says, and in the process he got to know many of the composers - such as Stravinsky, Ives and Varèse - who had forged the language of modernism in the first decades of the 20th century, as well as those like Boulez and Nono who led another musical revolution in the years after the second world war.

He may be the greatest composer the US has produced since Ives, but Carter's outlook has always been at least as much European as it is American, and it was audiences on this side of the Atlantic who first recognised the importance of his knotty, demanding music. Carter is a New Yorker: he was born there in 1908, and the city has remained his home throughout his life; he lives now in an apartment on the edge of Greenwich Village. But since childhood he has made regular visits to Europe, and expects to be in London once again next week - a 90% chance, he says - for the BBC's celebration of his music at the Barbican.

Carter's connections with Europe are deeply ingrained. He learned to speak French before he could read: "My father was an importer [of lace] from France, and he took me there many times when I was a child, so I am almost as familiar with Paris as I am with New York." Though Carter was given piano lessons (which he found boring at the time), his parents had no musical ambitions for their son, and expected him to make his career in the family business. It was not until his late teens, when he heard Stravinsky's Rite of Spring for the first time in 1924, that Carter realised what he really wanted to be was a composer.

Another European city he visited in the 1920s with his parents was Vienna, where he bought copies of the latest works by Schoenberg and other members of the Second Viennese School. Back in New York an enlightened music teacher took him to contemporary music concerts and, crucially, introduced him to Charles Ives ("He was not as isolated a man as he is sometimes made out to be," Carter says). Ives gave the schoolboy copies of the Concorde Sonata and the collection of his songs that had been privately printed, and became the guiding spirit behind Carter's first efforts at composition.

Nevertheless, when he became a student at Harvard University, Carter studied English, having decided the music department there was hopelessly conservative. He concentrated on composition only as a graduate student, when for one semester his teachers included Gustav Holst, whom he remembers as a rather melancholy old man. But by the time he left university he was still nowhere near to becoming the composer he wanted to be. "I tried to write the music that I wanted to write but couldn't do it, and I then realised those composers had a classical training, and so it was easy for me to be convinced that I should do that, too."

So in the 1930s, Carter spent three years in Paris studying with Nadia Boulanger. He arrived in 1933, at the time of the Reichstag fire, and found the city full of refugees from the Nazis, and "a very sad place". Boulanger's rigorous harmony and counterpoint exercises took him back to first principles, but also imbued him with the disciplines of neoclassicism, which ran counter to the much wilder, expressionist pieces he had got to know and tried to imitate in New York. "She wasn't encouraging if you wrote very dissonant music," Carter says. "But, meanwhile, the world of music had changed. It wasn't hard to think when we saw pictures of Hitler that it was expressionism that had gone on and produced such a terrible result in Germany, that it was a working out of that kind of extravagance that had become terrifying. So we thought that it was time to be more orderly and more consciously beautiful, and neoclassicism did seem to have a perfect logic about it."

The lessons he absorbed during his years of study with Boulanger remain paramount in his music today. With her he learned to write counterpoint in up to eight parts, and the virtuosity with which he was to invent the teeming lines of his greatest pieces, in which individual instruments often acquire a dramatic character of their own, was a direct result of his training. "To Nadia notes mattered a great deal, everything had to be justified. It was a whole world in which you had to think how every note fitted in; we were concerned not just with the detail of things, but with the total effect."

The music Carter composed when he returned to America was more or less faithful to the neoclassical ethos. But in his crucial pieces of the immediate postwar years - beginning with the 1946 Piano Sonata and culminating in 1951 in the arching sweep of the First String Quartet, the work that really established Carter's international reputation ("In this country you play it and people walk out, but in Europe it made a big impression") - he began the journey of self-discovery towards writing the music he wanted to compose. It was a process that lasted until 1980, during which period new works emerged with almost painful slowness. "Every one of those pieces is a new sort of thought. This was the way I was developing, until finally I felt that I had found my vocabulary and there was no longer any need to experiment."

During that period, too, it was his supporters in Europe rather than the US who championed Carter's music. The composer and conductor Pierre Boulez was an early convert, and, in Britain, William Glock, controller of music at the BBC from 1959 to 1973, was a fervent supporter. "William played all my music on the radio at one time or another and that was very influential, and I also taught at Dartington Summer School when Peter Maxwell Davies and Harry Birtwistle were students there." Stravinsky publicly admitted his admiration for Carter's 1962 Double Concerto for piano and harpsichord, proclaiming it a masterpiece, and the two composers became good friends. His mind, Carter says, is now filled with memories of Stravinsky: of the older composer's kindnesses to him and his wife, of having dinner in a New York restaurant when Frank Sinatra approached Stravinsky for his autograph, and of one of his last meetings with the composer in New York a couple of weeks before Stravinsky's death in 1971, when the only music the old man wanted to listen to was Mozart's Magic Flute.

Carter's music is still more highly regarded across Europe than in the US, yet he has always been in an important sense an American composer. He has regularly drawn inspiration from US writers such as Walt Whitman, Elizabeth Bishop, Robert Lowell, John Ashbery and Hart Crane; the new song cycle he is working on uses texts by Wallace Stevens. And Carter maintains that his musical language has always been intrinsically American: "I've always thought that in some very important way my pieces came from jazz - with a regular beat background and improvisations on top of that." But first and foremost he remains an unrepentant modernist, backing up his uncompromising stance with a cast-iron classical training. His music has its own cast-iron integrity, too, a fierceness and emotional power that is sometimes hard to square with the genial man one meets; great composers aren't supposed to be so courteous, and so charming, as Elliott Carter unfailingly is.

妙的是昨翻過楊牧的英漢對照本He may be the greatest composer the US has produced since Ives, but Carter's outlook has always been at least as much European as it is American, and it was audiences on this side of the Atlantic who first recognised the importance of his knotty, demanding music. Carter is a New Yorker: he was born there in 1908, and the city has remained his home throughout his life; he lives now in an apartment on the edge of Greenwich Village. But since childhood he has made regular visits to Europe, and expects to be in London once again next week - a 90% chance, he says - for the BBC's celebration of his music at the Barbican.

Carter's connections with Europe are deeply ingrained. He learned to speak French before he could read: "My father was an importer [of lace] from France, and he took me there many times when I was a child, so I am almost as familiar with Paris as I am with New York." Though Carter was given piano lessons (which he found boring at the time), his parents had no musical ambitions for their son, and expected him to make his career in the family business. It was not until his late teens, when he heard Stravinsky's Rite of Spring for the first time in 1924, that Carter realised what he really wanted to be was a composer.

Another European city he visited in the 1920s with his parents was Vienna, where he bought copies of the latest works by Schoenberg and other members of the Second Viennese School. Back in New York an enlightened music teacher took him to contemporary music concerts and, crucially, introduced him to Charles Ives ("He was not as isolated a man as he is sometimes made out to be," Carter says). Ives gave the schoolboy copies of the Concorde Sonata and the collection of his songs that had been privately printed, and became the guiding spirit behind Carter's first efforts at composition.

Nevertheless, when he became a student at Harvard University, Carter studied English, having decided the music department there was hopelessly conservative. He concentrated on composition only as a graduate student, when for one semester his teachers included Gustav Holst, whom he remembers as a rather melancholy old man. But by the time he left university he was still nowhere near to becoming the composer he wanted to be. "I tried to write the music that I wanted to write but couldn't do it, and I then realised those composers had a classical training, and so it was easy for me to be convinced that I should do that, too."

So in the 1930s, Carter spent three years in Paris studying with Nadia Boulanger. He arrived in 1933, at the time of the Reichstag fire, and found the city full of refugees from the Nazis, and "a very sad place". Boulanger's rigorous harmony and counterpoint exercises took him back to first principles, but also imbued him with the disciplines of neoclassicism, which ran counter to the much wilder, expressionist pieces he had got to know and tried to imitate in New York. "She wasn't encouraging if you wrote very dissonant music," Carter says. "But, meanwhile, the world of music had changed. It wasn't hard to think when we saw pictures of Hitler that it was expressionism that had gone on and produced such a terrible result in Germany, that it was a working out of that kind of extravagance that had become terrifying. So we thought that it was time to be more orderly and more consciously beautiful, and neoclassicism did seem to have a perfect logic about it."

The lessons he absorbed during his years of study with Boulanger remain paramount in his music today. With her he learned to write counterpoint in up to eight parts, and the virtuosity with which he was to invent the teeming lines of his greatest pieces, in which individual instruments often acquire a dramatic character of their own, was a direct result of his training. "To Nadia notes mattered a great deal, everything had to be justified. It was a whole world in which you had to think how every note fitted in; we were concerned not just with the detail of things, but with the total effect."

The music Carter composed when he returned to America was more or less faithful to the neoclassical ethos. But in his crucial pieces of the immediate postwar years - beginning with the 1946 Piano Sonata and culminating in 1951 in the arching sweep of the First String Quartet, the work that really established Carter's international reputation ("In this country you play it and people walk out, but in Europe it made a big impression") - he began the journey of self-discovery towards writing the music he wanted to compose. It was a process that lasted until 1980, during which period new works emerged with almost painful slowness. "Every one of those pieces is a new sort of thought. This was the way I was developing, until finally I felt that I had found my vocabulary and there was no longer any need to experiment."

During that period, too, it was his supporters in Europe rather than the US who championed Carter's music. The composer and conductor Pierre Boulez was an early convert, and, in Britain, William Glock, controller of music at the BBC from 1959 to 1973, was a fervent supporter. "William played all my music on the radio at one time or another and that was very influential, and I also taught at Dartington Summer School when Peter Maxwell Davies and Harry Birtwistle were students there." Stravinsky publicly admitted his admiration for Carter's 1962 Double Concerto for piano and harpsichord, proclaiming it a masterpiece, and the two composers became good friends. His mind, Carter says, is now filled with memories of Stravinsky: of the older composer's kindnesses to him and his wife, of having dinner in a New York restaurant when Frank Sinatra approached Stravinsky for his autograph, and of one of his last meetings with the composer in New York a couple of weeks before Stravinsky's death in 1971, when the only music the old man wanted to listen to was Mozart's Magic Flute.

Carter's music is still more highly regarded across Europe than in the US, yet he has always been in an important sense an American composer. He has regularly drawn inspiration from US writers such as Walt Whitman, Elizabeth Bishop, Robert Lowell, John Ashbery and Hart Crane; the new song cycle he is working on uses texts by Wallace Stevens. And Carter maintains that his musical language has always been intrinsically American: "I've always thought that in some very important way my pieces came from jazz - with a regular beat background and improvisations on top of that." But first and foremost he remains an unrepentant modernist, backing up his uncompromising stance with a cast-iron classical training. His music has its own cast-iron integrity, too, a fierceness and emotional power that is sometimes hard to square with the genial man one meets; great composers aren't supposed to be so courteous, and so charming, as Elliott Carter unfailingly is.

最後同意作者說的

莎士比亞對Berlioz影響大

不過他只是利用

Ariel 的話就姑且如此一記

等待

他人

↧

Alain de Botton (2) : The School of Life; Art Is Therapy review; 陳玉慧觀點:我們需要好新聞

| The School of Life 人才招募 | |

| |

The School of Life 總部位於英國倫敦,由英國作家艾倫.狄波頓 (Alain de Botton) 於2009年創立,透過文化和人文學科,探討關於工作、愛情、 The School of Life 總部位於英國倫敦,由英國作家艾倫.狄波頓 (Alain de Botton) 於2009年創立,透過文化和人文學科,探討關於工作、愛情、目前台北辦公室正熱烈招募以下職缺。有興趣加入The School of Life Taipei 師資或團隊成員,請聯繫 taipei@theschooloflife.com 師資 Faculty www.theschooloflife.com/ 事業發展暨行銷經理 Business Development & Marketing Manager www.theschooloflife.com/ | |

Alain de Botton : The News: A User’s Manual ; 幸福建築...

陳玉慧觀點:我們需要好新聞

陳玉慧 2014年05月08日 10:47

全文網址: 陳玉慧觀點:我們需要好新聞 -風傳媒http://www.stormmediagroup.com/opencms

Art Is Therapy review – de Botton as doorstepping self-help evangelist

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

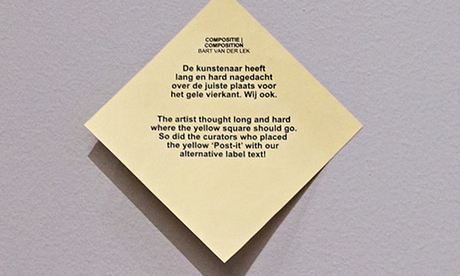

Alain de Botton has filled the Rijksmuseum with giant yellow Post-it notes that spell out his smarmy and banal ideas of self-improvement – but leaves us no room to look at the art

• Alain de Botton's exclusive video guide to Art is Therapy

Alain de Botton has filled the Rijksmuseum with giant yellow Post-it notes that spell out his smarmy and banal ideas of self-improvement – but leaves us no room to look at the art

• Alain de Botton's exclusive video guide to Art is Therapy

No eye, and no ear for language … the writer Alain de Botton at the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam. Photograph: Vincent Mentzel

A flashing neon sign hangs over the grand entrance to the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam. Art Is Therapy, it reads, mirroring the cover of Alain de Botton's recent book Art as Therapy, written with the philosopher and art historian John Armstrong.

The Rijksmuseum reopened last year after major reorganisation and restoration, to almost universal acclaim. It had more than 3 million visitors in 2013. They thought they had a museum; what they have is a crammed-to-the-gills tourist attraction. It's the Tate Modern effect.

Perhaps troubled that 3 million visitors was not quite enough, Rijksmuseum director Wim Pijbes invited De Botton and Armstrong to make an "intervention". The authors have filled the place with loud, intrusive labels – giant Post-it notes that often dwarf the exhibits – along with a number of thematic displays.

![Art Is Therapy, De Botton, Armstrong, Rijksmuseum]() No escape … one of the philosophers' labels at the Rijksmuseum. Photograph: Olivier Middendorp You can't avoid the crowds, and there is no escape from the labels: in the entrance hall, on the stairs, in the grand salons that connect the galleries, as well as beside and beneath the exhibits. People are spending longer reading the damn things than looking at the art.

No escape … one of the philosophers' labels at the Rijksmuseum. Photograph: Olivier Middendorp You can't avoid the crowds, and there is no escape from the labels: in the entrance hall, on the stairs, in the grand salons that connect the galleries, as well as beside and beneath the exhibits. People are spending longer reading the damn things than looking at the art.

"You suffer from fragility, guilt, a split personality, self disgust," reads a note next to Jan Steen's 1660s genre painting The Feast of Saint Nicholas. "You are probably a bit like this picture," the label goes on. "There are sides of you that are a little debauched." The labels tell us what's wrong with us, and how the artworks and artefacts they accompany can cure our ills.

In front of Rembrandt's Night Watch, the crowning glory of the collection, another big yellow label tells us what it believes we are thinking: "I can't bear busy places – I wish this room were emptier." De Botton sees the Night Watch as an image of communality, which I suppose it is. There's not much fellow-feeling in the audience around it, and I guess that's the point, too.

![De Botton, Armstrong, exhibition label]() One of the exhibition's yellow labels … Photograph: Olivier Middendorp Next to Vermeer's Woman Reading a Letter and his quiet Delft street scene, beside teapots and Chinese gods, alongside an Yves Saint Laurent dress and a Rietveld chair, the labels proliferate. De Botton is trying to mend what he sees as a disconnection between art and life, between past and present. This is an unexceptional ambition. Artists and designers do it all the time. Why do we need De Botton? In a display of 19thcentury daguerrotypes, under the curatorial theme of memory, we are told we are in "one of the saddest rooms in the museum. You might want to cry." Why? All the people in the pictures are dead. They generally are in photographs this old.

One of the exhibition's yellow labels … Photograph: Olivier Middendorp Next to Vermeer's Woman Reading a Letter and his quiet Delft street scene, beside teapots and Chinese gods, alongside an Yves Saint Laurent dress and a Rietveld chair, the labels proliferate. De Botton is trying to mend what he sees as a disconnection between art and life, between past and present. This is an unexceptional ambition. Artists and designers do it all the time. Why do we need De Botton? In a display of 19thcentury daguerrotypes, under the curatorial theme of memory, we are told we are in "one of the saddest rooms in the museum. You might want to cry." Why? All the people in the pictures are dead. They generally are in photographs this old.

Banality and bathos are the stock-in-trade here. De Botton's curatorial rubrics – as well as memory, there's fortune, money, politics and sex – are anodyne, his insights and descriptions shallow and obvious. De Botton insists that art can tell us how to live: "It should heal us: it isn't an intellectual exercise, an abstract aesthetic arena or a distraction for a Sunday afternoon." His petulant tone is wearing. I also dislike the self-improvement shtick. In front of an athletic bit of statuary, a label inquires why, if we can accept going to the gym to improve our bodies, we don't visit the museum "to work on our character".

![De Botton, Armstrong, Rijksmuseum]() Banality and bathos are the stock-in-trade … Photograph: Olivier Middendorp De Botton is like one of those "Jesus is your best mate" Christians, giving us not one but 150 thoughts for the day, on the ubiquitous labels, audioguide and downloadable app. He wants museums to become temples of virtue, places of instruction that go far beyond their usual remit of caring for and displaying centuries of culture. He'd probably also like to replace burgeoning museum education departments with outposts of his School of Life, a sort of drop-in self-help centre which, just this week, opened a branch in Amsterdam.

Banality and bathos are the stock-in-trade … Photograph: Olivier Middendorp De Botton is like one of those "Jesus is your best mate" Christians, giving us not one but 150 thoughts for the day, on the ubiquitous labels, audioguide and downloadable app. He wants museums to become temples of virtue, places of instruction that go far beyond their usual remit of caring for and displaying centuries of culture. He'd probably also like to replace burgeoning museum education departments with outposts of his School of Life, a sort of drop-in self-help centre which, just this week, opened a branch in Amsterdam.

De Botton thinks we've got art all wrong. He doesn't like the way museums are organised and finds the usual little wall labels, with their dates and movements and snippets of art history, unhelpful. Ideally, he envisages museums reorganised according to therapeutic functions – with a basement of suffering, leading upwards to a gallery of self-knowledge on the top floor. It's like Dante's circles of hell.

De Botton's evangelising and his huckster's sincerity make him the least congenial gallery guide imaginable. He has no eye, and no ear for language. With their smarmy sermons and symptomology of human failings, their aphorisms about art leading us to better parts of ourselves, De Botton's texts feel like being doorstepped. But art contains concentrated doses of the virtues! You could coerce any art at all into his cause of mental hygiene and spiritual wellbeing. De Botton reduces art to its discernible content. He doesn't make us want to look at all.

Until 7 September. Details: +31 20 674 7000. Venue: Rijksmuseum.

- Alain de Botton and John Armstrong

- Art Is Therapy

- Rijksmuseum,

- Amsterdam

- Until 7 September

- Details:

+31 20 6747 000 - Venue website

Perhaps troubled that 3 million visitors was not quite enough, Rijksmuseum director Wim Pijbes invited De Botton and Armstrong to make an "intervention". The authors have filled the place with loud, intrusive labels – giant Post-it notes that often dwarf the exhibits – along with a number of thematic displays.

No escape … one of the philosophers' labels at the Rijksmuseum. Photograph: Olivier Middendorp You can't avoid the crowds, and there is no escape from the labels: in the entrance hall, on the stairs, in the grand salons that connect the galleries, as well as beside and beneath the exhibits. People are spending longer reading the damn things than looking at the art.

No escape … one of the philosophers' labels at the Rijksmuseum. Photograph: Olivier Middendorp You can't avoid the crowds, and there is no escape from the labels: in the entrance hall, on the stairs, in the grand salons that connect the galleries, as well as beside and beneath the exhibits. People are spending longer reading the damn things than looking at the art."You suffer from fragility, guilt, a split personality, self disgust," reads a note next to Jan Steen's 1660s genre painting The Feast of Saint Nicholas. "You are probably a bit like this picture," the label goes on. "There are sides of you that are a little debauched." The labels tell us what's wrong with us, and how the artworks and artefacts they accompany can cure our ills.

In front of Rembrandt's Night Watch, the crowning glory of the collection, another big yellow label tells us what it believes we are thinking: "I can't bear busy places – I wish this room were emptier." De Botton sees the Night Watch as an image of communality, which I suppose it is. There's not much fellow-feeling in the audience around it, and I guess that's the point, too.

One of the exhibition's yellow labels … Photograph: Olivier Middendorp Next to Vermeer's Woman Reading a Letter and his quiet Delft street scene, beside teapots and Chinese gods, alongside an Yves Saint Laurent dress and a Rietveld chair, the labels proliferate. De Botton is trying to mend what he sees as a disconnection between art and life, between past and present. This is an unexceptional ambition. Artists and designers do it all the time. Why do we need De Botton? In a display of 19thcentury daguerrotypes, under the curatorial theme of memory, we are told we are in "one of the saddest rooms in the museum. You might want to cry." Why? All the people in the pictures are dead. They generally are in photographs this old.

One of the exhibition's yellow labels … Photograph: Olivier Middendorp Next to Vermeer's Woman Reading a Letter and his quiet Delft street scene, beside teapots and Chinese gods, alongside an Yves Saint Laurent dress and a Rietveld chair, the labels proliferate. De Botton is trying to mend what he sees as a disconnection between art and life, between past and present. This is an unexceptional ambition. Artists and designers do it all the time. Why do we need De Botton? In a display of 19thcentury daguerrotypes, under the curatorial theme of memory, we are told we are in "one of the saddest rooms in the museum. You might want to cry." Why? All the people in the pictures are dead. They generally are in photographs this old.Banality and bathos are the stock-in-trade here. De Botton's curatorial rubrics – as well as memory, there's fortune, money, politics and sex – are anodyne, his insights and descriptions shallow and obvious. De Botton insists that art can tell us how to live: "It should heal us: it isn't an intellectual exercise, an abstract aesthetic arena or a distraction for a Sunday afternoon." His petulant tone is wearing. I also dislike the self-improvement shtick. In front of an athletic bit of statuary, a label inquires why, if we can accept going to the gym to improve our bodies, we don't visit the museum "to work on our character".

Banality and bathos are the stock-in-trade … Photograph: Olivier Middendorp De Botton is like one of those "Jesus is your best mate" Christians, giving us not one but 150 thoughts for the day, on the ubiquitous labels, audioguide and downloadable app. He wants museums to become temples of virtue, places of instruction that go far beyond their usual remit of caring for and displaying centuries of culture. He'd probably also like to replace burgeoning museum education departments with outposts of his School of Life, a sort of drop-in self-help centre which, just this week, opened a branch in Amsterdam.

Banality and bathos are the stock-in-trade … Photograph: Olivier Middendorp De Botton is like one of those "Jesus is your best mate" Christians, giving us not one but 150 thoughts for the day, on the ubiquitous labels, audioguide and downloadable app. He wants museums to become temples of virtue, places of instruction that go far beyond their usual remit of caring for and displaying centuries of culture. He'd probably also like to replace burgeoning museum education departments with outposts of his School of Life, a sort of drop-in self-help centre which, just this week, opened a branch in Amsterdam.De Botton thinks we've got art all wrong. He doesn't like the way museums are organised and finds the usual little wall labels, with their dates and movements and snippets of art history, unhelpful. Ideally, he envisages museums reorganised according to therapeutic functions – with a basement of suffering, leading upwards to a gallery of self-knowledge on the top floor. It's like Dante's circles of hell.

De Botton's evangelising and his huckster's sincerity make him the least congenial gallery guide imaginable. He has no eye, and no ear for language. With their smarmy sermons and symptomology of human failings, their aphorisms about art leading us to better parts of ourselves, De Botton's texts feel like being doorstepped. But art contains concentrated doses of the virtues! You could coerce any art at all into his cause of mental hygiene and spiritual wellbeing. De Botton reduces art to its discernible content. He doesn't make us want to look at all.

Until 7 September. Details: +31 20 674 7000. Venue: Rijksmuseum.

↧

↧

Meredith Corp. Acquires Time Inc.

|

| Public | |

| Traded as | NYSE: MDP S&P 400 Component |

| Industry | Media |

| Founded | 1902 |

| Founder | Edwin T. Meredith |

| Headquarters | Des Moines, Iowa |

Key people | Steve Lacy (Chairman and CEO) Tom Harty (President and COO) |

| Products | Newspapers Magazines Television Educational Services Websites |

| Revenue | US$1.6 billion(2016)[1] |

Number of employees | 3,600 (2016)[1] |

| Divisions | National Media Local Media |

| Website | www |

The Meredith Corporation is an American media conglomeratebased in Des Moines, Iowa, USA. The company has two divisions: National Media and Local Media.

As of 2016, the company employs 3,600 people and has US$1.6billion in revenues.

Meredith Corp. Acquires Time Inc. in $2.8 Billion Koch Brothers-Backed Deal

CREDIT: AP/REX/SHUTTERSTOCK

Meredith Corp., a magazine publisher and broadcast company, will acquire Time Inc. in a deal totaling $2.8 billion, the company announced Sunday. The all-cash transaction is backed by an affiliate of Koch Industries, headed by the controversial billionaire brothers Charles and David Koch.

Des Moines, Iowa-based Meredith said in the statement the deal had been approved by both firms’ boards of directors and is expected to close in the first quarter. Meredith will pay $18.50 per share of the publicly traded Time Inc., a 46% premium over the closing price on Nov. 15, before reports of the acquisition surfaced.

Meredith chairman-CEO Stephen Lacy emphasized that the combined reach of the two companies would exceed 200 million consumers. The enlarged company would generate about $4.8 billion and adjust earnings of $800 million. Meredith said it expects to generate $400 million-$500 million of savings from streamlining operations during the first two years.

“We are adding the rich content-creation capabilities of some of the media industry’s strongest national brands to a powerful local television business that is generating record earnings, offering advertisers and marketers unparalleled reach to American adults,” Lacy said. “We are also creating a powerful digital media business with 170 million monthly unique visitors in the U.S. and over 10 billion annual video views, enhancing Meredith’s leadership position in reaching millennials.”

Meredith’s deal is backed by $650 million from Koch Equity Development, the investment arm of Koch Industries, an industrial conglomerate rooted in the oil and gas business. According to Meredith, KED will not have a seat on its board, and will have “no influence on Meredith’s editorial or managerial operations.”

The Koch brothers have become controversial figures for their lavish spending to back political candidates and causes, most of them conservative. By some estimates the pair spent nearly $1 billion during the 2016 federal election cycle. There is speculation that the brothers are diversifying their investments into media to have greater influence in culture and shaping popular opinion on issues such as tax policy and climate change.

KED has “deployed in excess of $8 billion of industry agnostic principal investments over the last five years,” Meredith said in announcing the deal.

As part of the transaction, Time Inc. CEO Rich Battista will step down once the deal is completed. He took the helm as Time Inc. CEO in September 2016. He joined Time Inc. as head of People and Entertainment Weekly in March 2015.

“I am proud of our accomplishments and thank the talented teams across the company for their extraordinary work, relentless commitment, and passion,” Battista said. “Together, we moved quickly and successfully to launch, grow, and advance our multi-platform offerings during unprecedented times in the media sector.”

The two companies had several rounds of acquisition talks in recent years, but were never able to come to a conclusive deal. Meredith’s best-known brands are Better Homes and Gardens and Family Circle, while New York-based Time Inc. is the home of Time magazine, Entertainment Weekly, People, Sports Illustrated, and Fortune.

The acquisition comes at a time when the print magazine business that Time Inc. helped build is struggling to retain readers and advertisers. Time Inc. earlier this month reported a 9% decrease in its revenue year-over-year for the third quarter and a 12% drop in advertising and circulation revenue.

Time Inc. was valued at about $4 billion in June 2014 when it was spun off from Time Warner. The 1989 merger of Time Inc. and Warner Communications helped usher in the era of mega media conglomerates.

↧

Rainer Maria Rilk's "Letters to a Young Poet' (1934);" Letters to a Young Painter"

“Perhaps all the dragons in our lives are princesses who are only waiting to see us act, just once, with beauty and courage. Perhaps everything that frightens us is, in its deepest essence, something helpless that wants our love.”

―from LETTERS TO A YOUNG POET by Rainer Maria Rilke

Letters written over a period of several years on the vocation of writing by a poet whose greatest work was still to come.

里爾克此書中譯夲全文,可在網路找到。

Vintage Books & Anchor Books

René Karl Wilhelm Johann Josef Maria Rilke was born in Prague, Bohemia, Austria-Hungary on this day in 1875.

"No one can advise or help you — no one. There is only one thing you should do. Go into yourself. Find out the reason that commands you to write; see whether it has spread its roots into the very depths of your heart; confess to yourself whether you would have to die if you were forbidden to write."

--Letter One (17 February 1903) from "Letters to a Young Poet' (1934) Rainer Maria Rilke

Letters written over a period of several years on the vocation of writing by a poet whose greatest work was still to come. Rainer Maria Rilke (1875–1926) is one of the greatest lyric German poets. Born in Prague, he published his first book of poems, Leben und Lieber, at age nineteen. He met Lou Salomé, the talented and spirited daughter of a Russian army officer, who influenced him deeply. In 1902 he became a friend, and for a time the secretary, of Rodin, and it was during his twelve-year Paris residence that Rilke enjoyed his greatest poetic activity. In 1919 he went to Switzerland where he spent the last years of his life. It was there that he wrote his last two works, Duino Elegies (1923) and The Sonnets to Orpheus (1923). READ an excerpt here:http://knopfdoubleday.com/b…/154358/letters-to-a-young-poet/

****

“It’s different for you,” Rainer Maria Rilke wrote to Balthus near the end of his life, “you will see the dawn to come after this night engulfing our world; you need to see it and call it and prepare for it with all your strength.”

Never before translated into English, Rainer Maria Rilke’s Letters to a Young Painter is a surprising companion to his earlier and far more famous Letters to a Young Poet. In eight intimate letters written to a teenage Balthus—who would go on to become one of the leading artists of his generation—Rilke encourages the young painter to take himself and his work seriously. Written toward the end of Rilke’s life, between 1920 and 1926, these letters paint a picture of the venerable poet as he faced his mortality, looked back on his life, and continued to embrace his openness toward other creative individuals. We have excerpted one of the letters below.

Château Muzot-sur-Sierre, Valais (Switzerland)

February 23, 1923

Dear Balthus,

In a few days you will once again celebrate the outward absence of your rare and discreet birthday. Many happy returns, my friend: let this year of your life about to commence be a happy and prosperous one—despite everything, I have to add, since it seems we have fallen back into the worst of the political turmoil that has already ruined so many years and that little by little deprives those of my generation of any reasonable future. It’s different for you, you will see the dawn to come after this night engulfing our world; you need to see it and call it and prepare for it with all your strength.

Now that you’ve been to Muzot and seen the shops we have in Sierre, you will understand perfectly why I have no choice but to come to your party empty-handed … Frida baked you a cake, but it won’t be able to come, poor thing. She just showed it to me and I had to agree it was neither transportable nor presentable. It’s more of a ghost story than a cake! Frida told me in a toneless voice, eyes still wide from her doleful vision: “At midnight, on the stroke of midnight, it half-collapsed!” Indeed, it is now a lunar cake, since if you look at it from one side only it admittedly looks magnificent, but that is not enough for a real Bundt cake, especially if you have to travel with it! She’s planning to make another one, but I’m afraid the mail is too slow, it probably won’t reach you in time for the party.

And here comes Minot to wish you a happy birthday, my dear Balthus. She’s an almost full-sized cat now, very smart, extremely sweet, and a big sleeper. The swipes are all used up, every last one, as we might have known they would be, and now she shows you her slow and empty paws with distracted caresses sleeping deep inside them.

Her kittenhood ended with a remarkable exploit: One night, a very cold night—I think it was still December—Frida (whose heart is not the most steadfast) had forgotten her out in the snow. At around midnight, practically the very moment when cakes half-collapse, what do you think this little creature dreamed up? She must have been circling the house trying to find some hole she could slip in through, then, not finding any, she climbed (just think, she’s so young!) up the tree next to the house, the plum tree, ventured all the way up to the top, then dared the magnificent leap onto my little balcony. From where, since the door is always open, she could come into my bedroom. I was woken up by her little voice, half plaintive, half angry, and at first I had no idea what she was doing there in the middle of the night … A “promising” display of intelligence, don’t you think?

Lately she’s been sleeping all night, every night, on the large woodburning stove in the dining room. As for her “job,” mice hardly interest her at all, she chases flies and wishes she could chase birds. But luckily for them, they learn in their schools that cats don’t have wings.

And you, my friend? How is the Academy of Art? You’re going there now, right? And do they like your Oriental piece? Or are the events of the “Ruhr” preventing all that? (As they are everything … )

Be strong, have courage, my dear, and be in good health, that’s all one can hope for when one is waiting. Very, very best wishes to Pierre and to your dear mother and your father, Balthus my dear.

Love,

RENÉ

Excerpted from Rainer Maria Rilke’s Letters to a Young Painter, translated by Damion Searls and published by David Zwirner Books.

Damion Searls, a former language columnist for the Daily, is an American translator and writer. He has translated thirty books from German, French, Norwegian, and Dutch, including The Inner Sky: Poems, Notes, Dreams (2010), a selection of writings by Rainer Maria Rilke. He is also the author of three books, most recently The Inkblots (2017), a scientific and cultural history of the Rorschach test and biography of its creator, Hermann Rorschach.

↧

Friedrich Engels, 《英國工人階級狀況》;( Friedrich) Engels By David McLellan 恩格斯傳; 烏克蘭的恩格斯雕像,胡不魂歸曼徹斯特。

Karl Marx is often named as one of the most important thinkers of the 19th century. But it was Friedrich Engels, his co-author and friend, who edited Marx's works after his death and opened them up to much more radical interpretations

#英國工人階級狀況”一書是弗·恩格斯1844年9月-1845年3月在巴門寫成的。恩格斯在英國居住期間(1842年11月-1844年8月)研究了英國無產階級的生活條件,他本來打算在他計劃寫的英國社會史中分出一章來說明這個問題,但是恩格斯為了要說明無產階級在資產階級社會中的特殊作用,便決定專門寫一本書來研究英國工人階級狀況。

本書的德文第一版在1845年在萊比錫出版,德文第二版在1892年出版。那時經作者同意的本書英譯本已出過兩版(1887年紐約版和1892年倫敦版)。恩格斯在準備出本書的新版時,並沒有做任何重大的修改。但是在1887年“美國版附錄”(這篇附錄的內容後來幾乎完全包括在1892年的英文版和德文版的序言中)中,恩格斯認為必須告訴讀者:不應當把“英國工人階級狀況”這本書當做一本成熟的馬克思主義的著作。他這樣寫道:“……在本書中到處都可以發現現代社會主義從它的祖先之一即德國古典哲學起源的痕跡。例如本書(特別是在末尾)大力強調:共產主義不純粹是工人階級的黨的學說,而且是一種理論,其最終目的就是把連同資本家在內的整個社會從現存關係的狹窄的範圍中解放出來。這個論斷在抽象的意義下是正確的,然而在實踐中卻是無益的,甚至多半是有害的。既然有產階級不但自己不感到有任何解放的需要,而且以全力反對工人階級的自我解放,那末工人階級就應當單獨地準備和進行社會革命。”接著,恩格斯就解釋,為什麼他在1845年所做的“英國將在最近發生社會革命”的預言沒有證實。他認為,1848年以後憲章運動的低潮和英國工人運動中機會主義的暫時勝利是與英國工業壟斷世界市場有直接聯繫的,並且他確信,一旦英國喪失了壟斷地位,“社會主義將重新在英國出現”。——編者註

本書的德文第一版在1845年在萊比錫出版,德文第二版在1892年出版。那時經作者同意的本書英譯本已出過兩版(1887年紐約版和1892年倫敦版)。恩格斯在準備出本書的新版時,並沒有做任何重大的修改。但是在1887年“美國版附錄”(這篇附錄的內容後來幾乎完全包括在1892年的英文版和德文版的序言中)中,恩格斯認為必須告訴讀者:不應當把“英國工人階級狀況”這本書當做一本成熟的馬克思主義的著作。他這樣寫道:“……在本書中到處都可以發現現代社會主義從它的祖先之一即德國古典哲學起源的痕跡。例如本書(特別是在末尾)大力強調:共產主義不純粹是工人階級的黨的學說,而且是一種理論,其最終目的就是把連同資本家在內的整個社會從現存關係的狹窄的範圍中解放出來。這個論斷在抽象的意義下是正確的,然而在實踐中卻是無益的,甚至多半是有害的。既然有產階級不但自己不感到有任何解放的需要,而且以全力反對工人階級的自我解放,那末工人階級就應當單獨地準備和進行社會革命。”接著,恩格斯就解釋,為什麼他在1845年所做的“英國將在最近發生社會革命”的預言沒有證實。他認為,1848年以後憲章運動的低潮和英國工人運動中機會主義的暫時勝利是與英國工業壟斷世界市場有直接聯繫的,並且他確信,一旦英國喪失了壟斷地位,“社會主義將重新在英國出現”。——編者註

中文馬克思主義文庫

【報導一則:恩格斯回到了曼徹斯特市!】

馬克思一生摯友和革命夥伴恩格斯,回到了英國曼徹斯特!2017年7月17日,曼徹斯特市國際節的活動高潮,為市中心特托尼威爾遜廣場(Tony Wilson Place)豎立的恩格斯雕像進行揭幕儀式。

這座雕像原本是在烏克蘭,因為後來右派政府上台而被拆除。 英國藝術家菲爾·柯林斯(Phil Collins),在烏克蘭東北部的哈爾科夫(Kharkiv)市發現了這座被遺棄的雕像,經過繁瑣的法律程序,終於成功將雕像帶離烏克蘭,安放在一架平板大卡車穿越歐洲最後回到了曼徹斯特。

恩格斯在曼市住了20年,目睹了新興資本主義生產的巨大發展,但同時也目睹資本主義的種種罪惡及剝削的一面,而寫下了名著《英國工人階級狀況》。

《英國工人階級狀況》全書連結:

https://www.marxists.org/chinese/engels/1844-1845/index.htm

https://www.marxists.org/chinese/engels/1844-1845/index.htm

照片來源:美國《雅各賓雜誌》(Jacobin magazine)臉書

David McLellan 1977恩格斯傳北京:中國人民大學,2017

Friedrich Engels was a German philosopher, social scientist, journalist, and businessman. He founded Marxist theory together with Karl Marx. Wikipedia

Born: November 28, 1820, Barmen, Germany

Died: August 5, 1895, London, United Kingdom

The state is nothing but an instrument of opression of one class by another - no less so in a democratic republic than in a monarchy.

All history has been a history of class struggles between dominated classes at various stages of social development.

An ounce of action is worth a ton of theory.

烏克蘭的恩格斯雕像,胡不魂歸曼徹斯特。

https://www.ft.com/content/205105fc-67c3-11e7-9a66-93fb352ba1fe

Back on his pedestal: the return of Friedrich Engels A socialist resurgence has revived the radicalism of the German Marxist thinker. Now the artist Phil Collins is bringing his statue back to the British city he called home Share on Twitter (opens new window) Share on Facebook (opens new window) Share on LinkedIn (opens new window) 6 Save 15 HOURS AGO by: John Lloyd The artist Phil Collins wanted to bring Friedrich Engels back to Manchester where, in the mid-19th century, he had lived for two decades. The German Marxist thinker established the first great industrial city in the annals of communist history with his excoriating 1845 polemic The Condition of the Working Class in England. But in the 171 years since his death, Manchester forgot about him. Collins told me his search for Engels was a “dream”. And it came true: he found him lying face down in the earth, long neglected, behind a creamery in Mala Pereshchepina, a few hours from the north-eastern Ukrainian city of Kharkiv. He was a man of two halves, sawn through at the waist, mouldy, unlovely, cast in concrete. His sorry condition told a wider story. After the Soviet Union emerged from the terror-driven idealism of the Stalinist era, party leader Leonid Brezhnev sought to hold up the USSR as a “developed” socialist state. Other gods were put into place: Lenin statuary was displayed everywhere, as were busts of Karl Marx and, less frequently, his friend and funder Engels. All gazed purposefully into the future. This one had been erected in 1970 and stood stonily in the village for several decades, a gentleman of the Victorian era in frock coat and long beard. Phil Collins in Zaporizhia, Ukraine with a statue of Vladimir Lenin that he was ultimately unable to bring back to the UK © Nikiforov Yevgen The collapse of Soviet communism two decades later saw many come off their pedestals — a culling that was more or less total in the satellite states. Some remained in the Russified areas of eastern Ukraine; but in 2015, as the conflict between Russia and Ukraine continued, an increasingly anti-Russian government decreed that Soviet symbols must be removed, pro-Soviet speech banned and even the singing of Soviet-era songs forbidden. So Collins, previously nominated for the Turner Prize for a video about people whose lives had been ruined by appearing on reality TV, came upon the object of his search when it was at a literal low point in its concrete existence. He and two Russian-speaking aides, Anya Harrison and Olga Borissova, had begun their search in August last year, sensibly enough, in the city of Engels, on the Volga. There they found a statue, also concrete, still standing amid the ruin of the meatpacking plant that had commissioned it. But the local authority, at first helpful, later proved fearful of giving the icon to foreigners at a time of east-west tension. It referred the decision to a court: a decision is still pending. With time running against them, the searchers moved on to the Belarusian city of Vitebsk, where they found a triptych statue — an Asian woman, an African man, with a white young man between them, embracing both, expressing the theme of brotherhood (and less overtly, Soviet leadership). Collins was tempted but it, too, was denied a visa. Collins with a statue of Engels that did not come back to the UK © Nikiforov Yevgen Finally they came to Mala Pereshchepina, where the local authorities were only too glad to get rid of what was by now a legally toxic artefact. In mid-May this year, the two-tonne, near-four-metre-high cement behemoth was loaded on to a flatbed truck to be trundled across Europe, to the city of Engels’ epiphany. This Sunday evening, when it is unveiled outside Home, a big modern arts building in Manchester largely funded by the city council, Collins’ quest will finally be at an end. The artist’s timing is impeccable. June’s UK general election saw a surge of support for the Labour party led by the far-left Jeremy Corbyn. Like Bernie Sanders in last year’s US Democratic primaries, this ageing socialist appealed first of all to the young. Marxism, which had been read the last rites by many, has found new life, reuniting its long-lonely intellectuals and academic advocates with the masses. The French economist Thomas Piketty’s 2013 book Capital in the Twenty-First Century, a self-conscious echo of Marx, was a huge seller. Commentators on the left are making connections between what Engels wrote and contemporary society. Writing in the Guardian after the fire at the Grenfell Tower block of flats in London, Aditya Chakrabortty explicitly linked the tragedy with The Condition of the Working Class, stating Britain “remains a country that murders its poor”. In such narratives, modern despair and marginalisation are laid at the feet of capitalism. The brutality of regimes working under Marxist rules — dramatised this week by the death of China’s most prominent dissident Liu Xiaobo, a few days after his release from long imprisonment — fades to the background. Collins believes that Engels is a writer “with whom we can engage today, with the questions he raises. He isn’t to be confined to his time and forgotten.” Engels’ writing shocked the Victorians. In The Condition of the Working Class he stressed that Britain’s wealth and imperial power (which impressed him), was built on the degradation and endless labour of hundreds of thousands of men, women and children, living in “half or wholly ruined buildings . . . rarely a wooden or stone floor to be seen in the houses, almost uniformly broken, ill-fitting windows and doors, and a state of filth!” Karl Marx, whom Engels had known slightly before he left Germany, was said to have been bewitched by the book. A villager in Mala Pereshchepina, Ukraine, with the statue of Engels that eventually came to Manchester © Shady Lane Productions The brutal world Engels described became a backdrop to some of the era’s best-known literature. The future prime minister, Benjamin Disraeli, published Sybil in 1845; Charles Dickens brought out Hard Times in 1854 and Mrs Gaskell North and South in 1855. All expressed horror at the human cost of industrialism, though with much more sentimentality and much less detail. Even now, when — for all the excesses of capitalism — the stark exploitation Engels evoked has disappeared in the western world, The Condition of the Working Class is an uncomfortable read. The homelessness of the rising generation; the precariousness of freelance work; the feared mass unemployment once artificial replaces human intelligence; the long, spiky tail of the banking collapse of 2008; the end of the postwar expectation that children will ascend further and richer than their parents — these are plausibly presented by the left as a 21st-century equivalent of the Condition of the Working, and even Middle Class of England, and the rest of the capitalist world. Looking out from Home’s café on to the space where Engels will finally rest — and remain — Sarah Perks, the centre’s artistic director for visual arts, tells me that discussion points will be created around the statue’s base to encourage viewers to become participants: “We want to try to understand what the equivalent hardships to those described by Engels would be for today’s working class.” *** Collins intersects with Engels in two ways. Born in the Cheshire port of Runcorn, he works mainly in Manchester. He also has a home in the North Rhine-Westphalia city of Wuppertal, where Engels was born to a pious and wealthy manufacturing family, mainly in the dyestuffs trade (he was already a fledgling socialist when sent by his despairing father to Manchester to work at one of his part-owned subsidiaries in the city). Moving the statue © Shady Lane Productions More than most contemporary artists on the left, Collins shows a strong sympathy for the communist era: one of his films, Marxism Today, is composed of tender interviews with former teachers of Marxism-Leninism in East Germany who were rendered unemployable by its collapse. “When the wall fell, there was also a collapse of something which had been solidarity, co-operative working: individualism flourished,” he says. First and foremost, though, he is engaged in an ironic, post-modernist project. He has taken an icon rejected by a recently socialist state as a sign of imperialist oppression to give it an honoured place in Manchester, the birthplace of industrial capitalism and of free trade. He sees Manchester as a city imbued with a kind of generic leftism: “There’s a Mancunian spirit of radicalism, an interest in politics and what it can do for people if properly managed.” He is most interested in “those who have been occluded from society or history” as Engels was in Manchester, where there is no statue to commemorate him. He thought it necessary to place him back in the city which he had described so graphically, to provide a contrast to the statues of local figures, some of whom — like Richard Cobden and John Bright, the proponents of free trade — were major national figures. On the long trip back from Ukraine to Manchester, he found that the huge, grubby, sundered statue “became a revelation: I felt more connected with him, he became suddenly real. It’s very alive — its physiognomy changed, depending on how it was placed, on the ground, or on the truck, or in the old train depot (its temporary home in Manchester).” The trip, which Collins filmed, featured a number of organised setpieces. In Kharkiv, a reception was arranged. “There were schoolchildren, and a teacher gave a lesson about Marx and Engels, Manchester and its importance, the Soviet Union, and the process of de-communisation. Then a girls’ choir, all in white, stood up on the truck and sang a Soviet-era song called ‘The Jolly Wind’ (presumably in defiance of the law), as they waved goodbye.” A choir of schoolchildren in Kharkiv, where a reception was arranged for the statue © Shady Lane Productions At Rosa Luxemburg Platz in Berlin (named after the communist activist murdered in the city in 1919) actors and others — many from the Volksbühne, or People’s Theatre — put on a show. There were speeches by academics belonging to the “accelerationist” school — a protean thought system with left and right branches, whose basis is the desire to speed up technological change to accelerate social transformation. The trip and the project display the artist’s ability to draw in myriad influences and strands, from kitsch through social realism and Soviet sentimentality for the loss of an authoritarianism they had experienced as security. Collins believes that, in the collapse of communism, “Something had been lost. The usual prism through which we saw, say, the East German society, was so strong that we didn’t see the ordinary; it frustrated our ability to see the day-to-day life.” He believes his Engels project “points to the fact we can have different kinds of statues here. It’s a found object, not something specially made. It’s transformative. It’s one kind of history coming back into the forge that created it.” *** The indifference of Manchester to Engels was noted by the former Labour MP Tristram Hunt in his fine biography, The Frock-Coated Communist. He found an Engels House on a council estate, where the residents complain of damp. In 2014, when the university in neighbouring Salford had the Engine Arts Theatre Company build a five-metre-high fibreglass Engels bust in which his vast beard was a climbing frame, one reviewer described it “as having all the intelligence and subtlety of making a see-saw shaped like Marx’s bum boils”. Things are changing, according to Jonathan Schofield, who writes about the city and conducts tours. Schofield thinks Manchester, along with other Midlands and northern cities, is shaking off its subaltern deference to London. “The provincial cities in the 19th century were more important than London. Now you’re finding a reawakening of civic pride: coming into their own again,” he says. He does a Marx and Engels tour that takes in Chetham’s Library, the oldest free library in the UK, opened in the mid-17th century through the bequest of Humphrey Chetham, a local merchant. “It’s the only building left where Engels definitely was. He worked with Marx at a table, still there, with the books they both used. When I take Chinese visitors to see it, some of them cry.” Vinnie Gavin (right) and his son Scott Gavin of 'Stone Central' work on restoring the statue of Friedrich Engels in Manchester in July © Greg Funnell For all the mass murders committed in their name, Marx and Engels continue to loom large today, not just in the consciousness of lachrymose visitors from China — where they remain on their pedestals. Their ideas are being revived beyond the lecture room. They represent a way not taken, a revolution betrayed. And on Sunday evening, Manchester’s first communist will be unveiled on a capitalist pedestal at last. John Lloyd is an FT contributing editor Photographs: Greg Funnell; Yevgen Nikiforov

https://www.ft.com/content/205105fc-67c3-11e7-9a66-93fb352ba1fe

Back on his pedestal: the return of Friedrich Engels A socialist resurgence has revived the radicalism of the German Marxist thinker. Now the artist Phil Collins is bringing his statue back to the British city he called home Share on Twitter (opens new window) Share on Facebook (opens new window) Share on LinkedIn (opens new window) 6 Save 15 HOURS AGO by: John Lloyd The artist Phil Collins wanted to bring Friedrich Engels back to Manchester where, in the mid-19th century, he had lived for two decades. The German Marxist thinker established the first great industrial city in the annals of communist history with his excoriating 1845 polemic The Condition of the Working Class in England. But in the 171 years since his death, Manchester forgot about him. Collins told me his search for Engels was a “dream”. And it came true: he found him lying face down in the earth, long neglected, behind a creamery in Mala Pereshchepina, a few hours from the north-eastern Ukrainian city of Kharkiv. He was a man of two halves, sawn through at the waist, mouldy, unlovely, cast in concrete. His sorry condition told a wider story. After the Soviet Union emerged from the terror-driven idealism of the Stalinist era, party leader Leonid Brezhnev sought to hold up the USSR as a “developed” socialist state. Other gods were put into place: Lenin statuary was displayed everywhere, as were busts of Karl Marx and, less frequently, his friend and funder Engels. All gazed purposefully into the future. This one had been erected in 1970 and stood stonily in the village for several decades, a gentleman of the Victorian era in frock coat and long beard. Phil Collins in Zaporizhia, Ukraine with a statue of Vladimir Lenin that he was ultimately unable to bring back to the UK © Nikiforov Yevgen The collapse of Soviet communism two decades later saw many come off their pedestals — a culling that was more or less total in the satellite states. Some remained in the Russified areas of eastern Ukraine; but in 2015, as the conflict between Russia and Ukraine continued, an increasingly anti-Russian government decreed that Soviet symbols must be removed, pro-Soviet speech banned and even the singing of Soviet-era songs forbidden. So Collins, previously nominated for the Turner Prize for a video about people whose lives had been ruined by appearing on reality TV, came upon the object of his search when it was at a literal low point in its concrete existence. He and two Russian-speaking aides, Anya Harrison and Olga Borissova, had begun their search in August last year, sensibly enough, in the city of Engels, on the Volga. There they found a statue, also concrete, still standing amid the ruin of the meatpacking plant that had commissioned it. But the local authority, at first helpful, later proved fearful of giving the icon to foreigners at a time of east-west tension. It referred the decision to a court: a decision is still pending. With time running against them, the searchers moved on to the Belarusian city of Vitebsk, where they found a triptych statue — an Asian woman, an African man, with a white young man between them, embracing both, expressing the theme of brotherhood (and less overtly, Soviet leadership). Collins was tempted but it, too, was denied a visa. Collins with a statue of Engels that did not come back to the UK © Nikiforov Yevgen Finally they came to Mala Pereshchepina, where the local authorities were only too glad to get rid of what was by now a legally toxic artefact. In mid-May this year, the two-tonne, near-four-metre-high cement behemoth was loaded on to a flatbed truck to be trundled across Europe, to the city of Engels’ epiphany. This Sunday evening, when it is unveiled outside Home, a big modern arts building in Manchester largely funded by the city council, Collins’ quest will finally be at an end. The artist’s timing is impeccable. June’s UK general election saw a surge of support for the Labour party led by the far-left Jeremy Corbyn. Like Bernie Sanders in last year’s US Democratic primaries, this ageing socialist appealed first of all to the young. Marxism, which had been read the last rites by many, has found new life, reuniting its long-lonely intellectuals and academic advocates with the masses. The French economist Thomas Piketty’s 2013 book Capital in the Twenty-First Century, a self-conscious echo of Marx, was a huge seller. Commentators on the left are making connections between what Engels wrote and contemporary society. Writing in the Guardian after the fire at the Grenfell Tower block of flats in London, Aditya Chakrabortty explicitly linked the tragedy with The Condition of the Working Class, stating Britain “remains a country that murders its poor”. In such narratives, modern despair and marginalisation are laid at the feet of capitalism. The brutality of regimes working under Marxist rules — dramatised this week by the death of China’s most prominent dissident Liu Xiaobo, a few days after his release from long imprisonment — fades to the background. Collins believes that Engels is a writer “with whom we can engage today, with the questions he raises. He isn’t to be confined to his time and forgotten.” Engels’ writing shocked the Victorians. In The Condition of the Working Class he stressed that Britain’s wealth and imperial power (which impressed him), was built on the degradation and endless labour of hundreds of thousands of men, women and children, living in “half or wholly ruined buildings . . . rarely a wooden or stone floor to be seen in the houses, almost uniformly broken, ill-fitting windows and doors, and a state of filth!” Karl Marx, whom Engels had known slightly before he left Germany, was said to have been bewitched by the book. A villager in Mala Pereshchepina, Ukraine, with the statue of Engels that eventually came to Manchester © Shady Lane Productions The brutal world Engels described became a backdrop to some of the era’s best-known literature. The future prime minister, Benjamin Disraeli, published Sybil in 1845; Charles Dickens brought out Hard Times in 1854 and Mrs Gaskell North and South in 1855. All expressed horror at the human cost of industrialism, though with much more sentimentality and much less detail. Even now, when — for all the excesses of capitalism — the stark exploitation Engels evoked has disappeared in the western world, The Condition of the Working Class is an uncomfortable read. The homelessness of the rising generation; the precariousness of freelance work; the feared mass unemployment once artificial replaces human intelligence; the long, spiky tail of the banking collapse of 2008; the end of the postwar expectation that children will ascend further and richer than their parents — these are plausibly presented by the left as a 21st-century equivalent of the Condition of the Working, and even Middle Class of England, and the rest of the capitalist world. Looking out from Home’s café on to the space where Engels will finally rest — and remain — Sarah Perks, the centre’s artistic director for visual arts, tells me that discussion points will be created around the statue’s base to encourage viewers to become participants: “We want to try to understand what the equivalent hardships to those described by Engels would be for today’s working class.” *** Collins intersects with Engels in two ways. Born in the Cheshire port of Runcorn, he works mainly in Manchester. He also has a home in the North Rhine-Westphalia city of Wuppertal, where Engels was born to a pious and wealthy manufacturing family, mainly in the dyestuffs trade (he was already a fledgling socialist when sent by his despairing father to Manchester to work at one of his part-owned subsidiaries in the city). Moving the statue © Shady Lane Productions More than most contemporary artists on the left, Collins shows a strong sympathy for the communist era: one of his films, Marxism Today, is composed of tender interviews with former teachers of Marxism-Leninism in East Germany who were rendered unemployable by its collapse. “When the wall fell, there was also a collapse of something which had been solidarity, co-operative working: individualism flourished,” he says. First and foremost, though, he is engaged in an ironic, post-modernist project. He has taken an icon rejected by a recently socialist state as a sign of imperialist oppression to give it an honoured place in Manchester, the birthplace of industrial capitalism and of free trade. He sees Manchester as a city imbued with a kind of generic leftism: “There’s a Mancunian spirit of radicalism, an interest in politics and what it can do for people if properly managed.” He is most interested in “those who have been occluded from society or history” as Engels was in Manchester, where there is no statue to commemorate him. He thought it necessary to place him back in the city which he had described so graphically, to provide a contrast to the statues of local figures, some of whom — like Richard Cobden and John Bright, the proponents of free trade — were major national figures. On the long trip back from Ukraine to Manchester, he found that the huge, grubby, sundered statue “became a revelation: I felt more connected with him, he became suddenly real. It’s very alive — its physiognomy changed, depending on how it was placed, on the ground, or on the truck, or in the old train depot (its temporary home in Manchester).” The trip, which Collins filmed, featured a number of organised setpieces. In Kharkiv, a reception was arranged. “There were schoolchildren, and a teacher gave a lesson about Marx and Engels, Manchester and its importance, the Soviet Union, and the process of de-communisation. Then a girls’ choir, all in white, stood up on the truck and sang a Soviet-era song called ‘The Jolly Wind’ (presumably in defiance of the law), as they waved goodbye.” A choir of schoolchildren in Kharkiv, where a reception was arranged for the statue © Shady Lane Productions At Rosa Luxemburg Platz in Berlin (named after the communist activist murdered in the city in 1919) actors and others — many from the Volksbühne, or People’s Theatre — put on a show. There were speeches by academics belonging to the “accelerationist” school — a protean thought system with left and right branches, whose basis is the desire to speed up technological change to accelerate social transformation. The trip and the project display the artist’s ability to draw in myriad influences and strands, from kitsch through social realism and Soviet sentimentality for the loss of an authoritarianism they had experienced as security. Collins believes that, in the collapse of communism, “Something had been lost. The usual prism through which we saw, say, the East German society, was so strong that we didn’t see the ordinary; it frustrated our ability to see the day-to-day life.” He believes his Engels project “points to the fact we can have different kinds of statues here. It’s a found object, not something specially made. It’s transformative. It’s one kind of history coming back into the forge that created it.” *** The indifference of Manchester to Engels was noted by the former Labour MP Tristram Hunt in his fine biography, The Frock-Coated Communist. He found an Engels House on a council estate, where the residents complain of damp. In 2014, when the university in neighbouring Salford had the Engine Arts Theatre Company build a five-metre-high fibreglass Engels bust in which his vast beard was a climbing frame, one reviewer described it “as having all the intelligence and subtlety of making a see-saw shaped like Marx’s bum boils”. Things are changing, according to Jonathan Schofield, who writes about the city and conducts tours. Schofield thinks Manchester, along with other Midlands and northern cities, is shaking off its subaltern deference to London. “The provincial cities in the 19th century were more important than London. Now you’re finding a reawakening of civic pride: coming into their own again,” he says. He does a Marx and Engels tour that takes in Chetham’s Library, the oldest free library in the UK, opened in the mid-17th century through the bequest of Humphrey Chetham, a local merchant. “It’s the only building left where Engels definitely was. He worked with Marx at a table, still there, with the books they both used. When I take Chinese visitors to see it, some of them cry.” Vinnie Gavin (right) and his son Scott Gavin of 'Stone Central' work on restoring the statue of Friedrich Engels in Manchester in July © Greg Funnell For all the mass murders committed in their name, Marx and Engels continue to loom large today, not just in the consciousness of lachrymose visitors from China — where they remain on their pedestals. Their ideas are being revived beyond the lecture room. They represent a way not taken, a revolution betrayed. And on Sunday evening, Manchester’s first communist will be unveiled on a capitalist pedestal at last. John Lloyd is an FT contributing editor Photographs: Greg Funnell; Yevgen Nikiforov

↧

宮澤賢治詩集:《春天與阿修羅》《不要輸給風雨》

文字來源

http://www.books.com.tw/products/0010697939

-----

宮澤賢治是"前西洋科學概念"的詩人,即,佛教遠比科學觀更早在他生根。

春天與阿修羅

作者: (日)宮澤賢治

出版社:新星出版社

出版日期:2015/09/01

語言:簡體中文

《春天與阿修羅》是宮澤賢治的一部詩集。作為曾經的詩壇「異類」,宮澤賢治至今仍是昭和詩人中獨特的,也是日本影響力大的詩人之一,被選為日本千年來偉大的作家第四位。

《春天與阿修羅》開宇宙詩風之先河,代表了早期現代詩歌的成就,中原中也、谷川俊太郎等名家直言受其巨大的影響。

宮澤的魅力來自於他科學家般的眼睛、哲學家般的智慧,以及一顆詩人的心(日本詩人村野四郎)

如果說詩人,一百餘年的日本也就三個:宮澤賢治、中原中也、谷川俊太郎。(日本大思想家加藤周一)

偉大是一個非常重的詞,宮澤賢治、中原中也等人都是非常好的詩人,其中宮澤賢治接近偉大。(日本國民詩人谷川俊太郎)

(日本)宮澤賢治,日本國民詩人與兒童文學巨匠。全國各地的小學、國中的國語課本都可見他的作品。

2000年,日本《朝日新聞》進行了一項調查,由作者自由投票選出「一千年里巨受歡迎的日本文學家」,宮澤賢治名列第四,遠遠超過了太宰治、谷崎潤一郎、川端康成、三島由紀夫、安部公房、大江健三郎和村上春樹。

代表作有《銀河鐵道之夜》《風又三郎》,詩集《春天與阿修羅》等。

吳菲,畢業於日本山口大學人文科學研究科語言文化專業,文學碩士。譯作有《向着明亮的那方》《西域余聞》《浮雲》《手鎖心中》等。

目錄

卷一及補遺

卷二及其他

*****

不要輸給風雨:宮澤賢治詩集

作者: 宮澤賢治

譯者:顧錦芬

內容簡介

宮澤賢治先生120週年誕生紀念

華語圈首部宮澤賢治純詩集,

收錄除了〔不輸給雨〕、〈永訣之朝〉外,

多首從未中譯的宮澤賢治經典詩作

所謂 我 的這個現象

是被假設的有機交流電燈的

一抹藍色照明

隨著風景以及大家一起

忙忙碌碌地明滅

就像是真的繼續點著的

因果交流電燈的

一抹藍色照明

BY 宮澤賢治

永久的未完成 這就是完成

BY 宮澤賢治

宮澤賢治是日本最受歡迎的國民作家之一。短短37年人生,除了童話之外,賢治一共創作了八百多首詩,絕大多數都沒有公開發表,少量則集結成《春天與修羅》,以自費的方式發行出版。

賢治生前作品乏人問津,卻在逝世後,成為日本家喻戶曉的國民作家,作品被收錄在課本中。又因其強大的精神感召力,成為日本人的心靈原鄉與文學象徵之一。日本311大震後,演員渡邊謙朗讀宮澤賢治的名作:〔不輸給雨〕,撫慰了千萬人心。

宮澤賢治的作品帶著強烈的玄想色彩,大量運用自然的象徵物與情境,乍讀也許悲傷,卻又可以感受到生之強韌與力量,以及對人和土地的深層關懷。日本近代著名詩人高村光太郎就曾說過:

胸懷宇宙者,無論身處多麼偏遠處,總是能超越地方性而存在。內心沒有宇宙者,無論身處多麼核心的文化之地,也只是一個地方性的存在。岩手縣花卷的詩人宮澤賢治就是罕見的胸懷宇宙的人。他所謂的伊哈托布,就是藉由他內心的宇宙所表達出來的這世界全部。

本詩集譯出大部分的《春天與修羅》,收錄「宮澤賢治關鍵語彙小辭典」,其他項目則斟酌採選較著名或是對於理解賢治有幫助的作品。希望與華文圈的讀者,共同分享這個有著深邃心靈的詩人內心的風景。

![]()

譯者:顧錦芬

內容簡介

宮澤賢治先生120週年誕生紀念

華語圈首部宮澤賢治純詩集,

收錄除了〔不輸給雨〕、〈永訣之朝〉外,

多首從未中譯的宮澤賢治經典詩作

所謂 我 的這個現象

是被假設的有機交流電燈的

一抹藍色照明

隨著風景以及大家一起

忙忙碌碌地明滅

就像是真的繼續點著的

因果交流電燈的

一抹藍色照明

BY 宮澤賢治

永久的未完成 這就是完成

BY 宮澤賢治

宮澤賢治是日本最受歡迎的國民作家之一。短短37年人生,除了童話之外,賢治一共創作了八百多首詩,絕大多數都沒有公開發表,少量則集結成《春天與修羅》,以自費的方式發行出版。

賢治生前作品乏人問津,卻在逝世後,成為日本家喻戶曉的國民作家,作品被收錄在課本中。又因其強大的精神感召力,成為日本人的心靈原鄉與文學象徵之一。日本311大震後,演員渡邊謙朗讀宮澤賢治的名作:〔不輸給雨〕,撫慰了千萬人心。

宮澤賢治的作品帶著強烈的玄想色彩,大量運用自然的象徵物與情境,乍讀也許悲傷,卻又可以感受到生之強韌與力量,以及對人和土地的深層關懷。日本近代著名詩人高村光太郎就曾說過:

胸懷宇宙者,無論身處多麼偏遠處,總是能超越地方性而存在。內心沒有宇宙者,無論身處多麼核心的文化之地,也只是一個地方性的存在。岩手縣花卷的詩人宮澤賢治就是罕見的胸懷宇宙的人。他所謂的伊哈托布,就是藉由他內心的宇宙所表達出來的這世界全部。

本詩集譯出大部分的《春天與修羅》,收錄「宮澤賢治關鍵語彙小辭典」,其他項目則斟酌採選較著名或是對於理解賢治有幫助的作品。希望與華文圈的讀者,共同分享這個有著深邃心靈的詩人內心的風景。

↧

↧

Rilke:The Book of Hours, “The Lion Cage,”

Rainer Maria Rilke was born on this day in 1875. Read this excerpt from “The Lion Cage.”

Leo Tolstoy, by Leonid Pasternak

Rainer Maria Rilke

You, my own deep soul,

trust me. I will not betray you.

My blood is alive with many voices

telling me I am made of longing.

What mystery breaks over me now?

In its shadow I come into life.

For the first time I am alone with you—

you, my power to feel.

From The Book of Hours I, 39

"Archaic Torso of Apollo" by Rainer Maria Rilke (1875-1926)

We cannot know his legendary head

with eyes like ripening fruit. And yet his torso

is still suffused with brilliance from inside,

like a lamp, in which his gaze, now turned to low,

with eyes like ripening fruit. And yet his torso

is still suffused with brilliance from inside,

like a lamp, in which his gaze, now turned to low,

gleams in all its power. Otherwise

the curved breast could not dazzle you so, nor could

a smile run through the placid hips and thighs

to that dark center where procreation flared.

the curved breast could not dazzle you so, nor could

a smile run through the placid hips and thighs

to that dark center where procreation flared.

Otherwise this stone would seem defaced

beneath the translucent cascade of the shoulders

and would not glisten like a wild beast’s fur:

beneath the translucent cascade of the shoulders

and would not glisten like a wild beast’s fur:

would not, from all the borders of itself,