Six Hundred Thousand Faces

What Gershom Scholem’s take on Jewish mysticism can teach us now.

In the wake of so much political turmoil, we’re hungry for books that diagnose our broken world: books that lay out a grand ethical program and claw back some hope for humanity. Online, I’ve noticed a loose reading list coalescing. We’ve called on Hannah Arendt, who cut into the heart of evil and found a weak organ of banality instead of an engine of diabolic creativity; Walter Benjamin and his “weak messianic power,” which inspired us with the latent energy of history’s failed revolutions; the totalitarian gloom of 1984 and The Handmaid’s Tale; the grim prescience of Richard Rorty’s Achieving Our Country. Surely, the thinking goes, we could be saved if we find the proper pattern, fitting our dismal and uncertain present to the prescriptions of history.

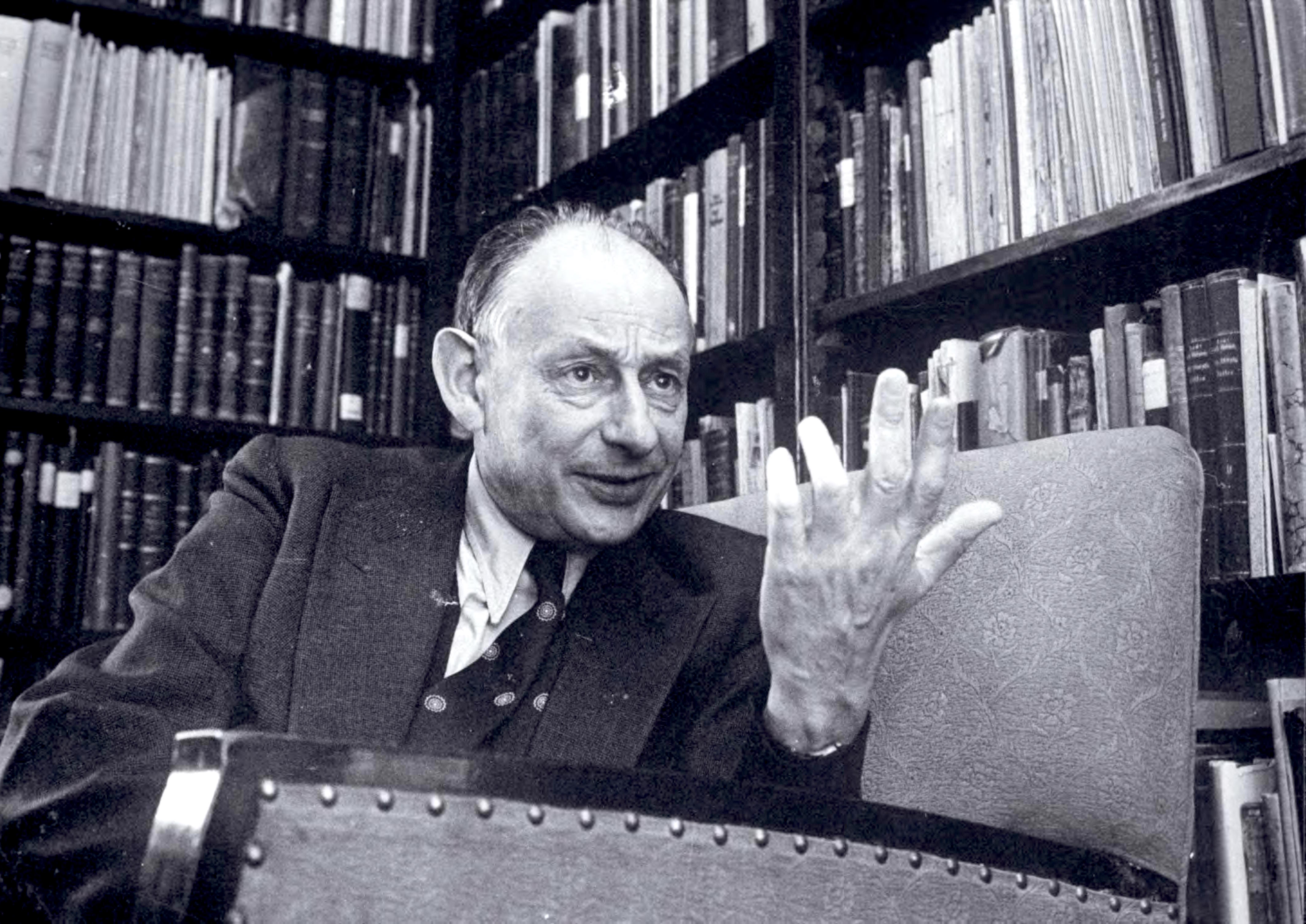

In Gershom Scholem, the historian who popularized the study of Kabbalistic and Messianic movements in Judaism, I’ve found a refreshing vision of revolutionary change and justice, stimulating the utopian imagination beyond the traditional touchstones of leftist thought. Though he was a friend of Benjamin’s and, more distantly, of Arendt’s, Scholem is the least widely read of the three and arguably the least accessible. A scholar of esoteric Jewish experience who rarely divulged his personal religious and political philosophy, Scholem resists the immediate, quotable relevance enjoyed by his contemporaries. His work features ecstatic stories of men who believed they were the Messiah, and incoherent descriptions of God’s celestial chariot—of limited use to political dissidents, war victims, and alienated workers. When the jackboots of authoritarianism are kicking in doors, Scholem’s apocalyptic religiosity can seem cloying. Why should we need to hallucinate the end of days? It’s here.

But Scholem wrote from a similar vantage. An adolescent and budding anarchist in Germany during World War I, he found himself trapped between a zealous nationalism and a bourgeois Jewish community that little nothing to prevent the bloodshed. Even the supposedly revolutionary Zionist movement, which enchanted Scholem, proved to be a disappointment when Martin Buber, one of its most influential intellectuals, endorsed the war. Later, after Scholem had moved to Jerusalem on a spiritual quest to deepen his engagement with Jewish literature and tradition, still trying to salvage redemptive threads of the cultural Zionist project, he again encountered devastation. The idealized return to the holy land engulfed Palestine in violence, culminating in the 1929 riots that claimed hundreds of Jewish and Arab lives. “Zionism has triumphed itself to death,” Scholem wrote in a 1931 letter to Walter Benjamin. “Now it is no longer a matter of saving us … but of jumping into the abyss that yawns between victory and reality.” A decade later, he witnessed the unimaginable tragedy of World War II and the Holocaust, which took the life of his close friend, Walter Benjamin, murdered his brother Werner, and annihilated much of European Jewry.

Scholem reacted to these waves of devastation by turning to the study of mystical movements in Jewish history. Working in Jerusalem at the National Library and, eventually, as a professor of Jewish mysticism at the Hebrew University, he revitalized interest in Kabbalah, an esoteric tradition within Judaism. Dating back to the Talmudic era and thoroughly multifarious, Kabbalah is a mystical complement to Jewish religious life, driven by linguistic and metaphysical speculation. Rather than relegate the ecstatic and obscure threads of Kabbalah to a para-religious curiosity, Scholem detailed the evolution of Judaism as one that braided its mainline and mystical elements. In perhaps the best introduction to Scholem’s thought, his “Religious Authority and Mysticism,” he writes, “All mysticism has two contradictory or complementary aspects: the one conservative, the other revolutionary.” In his story of Judaism, the conservative tenets of the religion are tempered, subverted, and reinvented by mystical influences: blind sages meditating on the divine qualities of Hebrew letters, secretive rabbis forging mammoth tomes of speculative philosophy, and charismatic cult leaders claiming that they were the messiah. For Scholem, the history of Jewish mysticism held tradition open to innovation. He imagined a politics and ethics vitalized by an anarchistic spirit.

*

Why should a religious historian have any particular relevance to us now? After all, though he was a prolific scholar and an avid letter writer, Scholem rarely articulated his own philosophies, and he composed no sustained works of social critique. In 1960, he wrote to a friend, “I have made myself into one of the figures who camouflages himself in famous paintings.” He recedes into the negative space between his tableaus of historic mystical experience. In this absence, though, he articulates a radical vision of knowledge and truth.

In Stranger in a Strange Land, an excellent new biography of Scholem, George Prochnik writes: “Through all the provocative ideas that glittered through his writing, there was one concept that cropped up repeatedly, as a kind of choral refrain, which I found galvanizing: Kabbalah preserved the frame of monotheism while shattering the idol of monolithic truth.” Kabbalah never questions the ultimate authority of God. Instead, it transforms what it means to know this authority, bracketing human understanding as always falling short. God’s word is absolute, but withdrawn; eternally valid but always open for reinterpretation.

“The absolute word is as such meaningless, but it is pregnant with meaning,” Scholem writes. The divine can never be translated into human description or codified into law. Truth is always postponed, and the religious individual must labor in the impossible task of its comprehension and communication. This exertion creates a deep religious life, invulnerable to the stultifying effects of mundane obedience. “But it is precisely the shapeless core of his experience which spurs the mystic to his understanding of his religious world and its values … Here all religious authority is destroyed in the name of authority: here we have the revolutionary aspect of mysticism in its purest form.”

The image of a pious individual exploring an unsayable truth, wandering toward a withdrawn God, animates Scholem’s body of work. Mysticism argues that our systems of rationality and knowledge are always incomplete. Here Scholem finds a revolutionary religious spirit that won’t harden into orthodoxy: a mystical character moored to tradition, but still plastic.

This balance of conservative and revolutionary impulses fascinated Scholem, even in his earliest work. In his 1918 piece “The Bolshevik Revolution,” a young Scholem worries that although the revolution will be “the only high-point of the history of the world war,” it is ultimately compromised. Motivated by discrete ideology rather than a supernal dictate to strive toward a postponed good, the revolution justifies its authority and violence with the rigid rules of worldly philosophy. It will congeal into injustice and orthodoxy—the revolution will swallow its revolutionary character. Scholem wrestles with this self-eradicating character of revolution for his entire career, finding in Jewish mysticism a strange remedy. As long as knowledge can only tilt at an eternal and inaccessible truth, the revolution is sustained, bathed in the restorative waters of a continually reinterpreted tradition. For Scholem, this constant revolution held together by tradition, is his anarchistic, mystical utopia.

Now, more than ever, this strange utopia is worth reflecting on. Public interest in leftist thought has been reinvigorated by the rise of brutal nationalism and the collapse of neoliberalism’s Potemkin civility. We would be wise to take notes from Scholem, who found himself in a similar point of historical inflection. If we want these new transformative currents to elude the snares that have trapped and divided the left for a century, we need new, vitalizing material. Though there’s no shortage of postwar authors who punched against leftist orthodoxy on social, philosophical, and economic grounds—C.L.R. James, Chantal Mouffe, and Alexis Shotwell, to name a few of the best—Scholem occupies a unique position. He criticized radical projects as not revolutionary enough from the unconventional perspective of religious anarchism. Rather than relitigate the well-worn conflicts of economism, historicism, Stalinism, or the other hobbyhorses of internecine sparring on the left, Scholem charted another path, bursting with imaginative and anarchic potential.

If you’re interested in reading more about Scholem, Prochnik’s Stranger is the best place to start—it elegantly tracks Prochnik’s experiences in modern Jerusalem against Scholem’s life. As for Scholem work itself, I’d recommend the aforementioned essay in his collection On the Kabbalah and Its Symbolism, “Religious Authority and Mysticism.” It’s filled with colorful anecdotes and summarizes many of his motifs: divine inaccessibility, mystical creativity, and a history of revolutionary moments in the development of Jewish thought. In one of its most memorable sections, Scholem sketches such a world with a Kabbalistic reading of Moses delivering the law:

Every world of the Torah has six hundred thousand ‘faces.’ That is, layers of meaning or entrances, one for each of the children of Israel who stood at the foot of Mount Sinai. Each face is turned toward only one of them; he alone can see it and decipher it. Each man has his own unique access to Revelation. Authority no longer resides in a single unmistakable ‘meaning’ of the divine communication, but in its infinite capacity for taking on new forms.

Here we hear echoes of a rear-guardism that doesn’t destroy all authority, but radically democratizes it. Rummaging around in Scholem’s universe, dense as it is with esoteric symbols and stories, is revitalizing even when it’s not easy. Don’t let that frustrate you. His insight was that we don’t have master the truth to be transformed by it.

Erik Hinton is a developer and journalist focusing on interactive news. He currently works at The Outline. His work has previously appeared in the New York Times, the Wall Street Journal, andVICE.

這幅畫在1921年由舒勒姆購得,家境富裕與年輕的舒勒姆將這幅畫送給班傑明做為生日禮物。舒勒姆〈Gershom Scholem, 1897-1982〉後來成為猶太史學家,班傑明〈Walter Benjamin, 1892-1940〉則為當代重要的思想家,與國人較為熟悉的漢娜鄂蘭有姻親關係。如同那時歐陸的猶太人,班傑明痛苦地活在兩次世界大戰之間,一戰後的德國猶太人更是風聲鶴唳。納粹掌權前夕班傑明逃離德國來到巴黎,1940年巴黎淪陷後再度逃亡,卻在越過法境後被占領加泰隆尼亞的佛朗哥政權查獲。彼時血腥的西班牙內戰剛結束,法西斯佛朗哥與希特勒一個鼻孔出氣,班傑明面臨遣返與送往集中營的命運,最後自殺身亡。班傑明的自殺是思想界重大的損失,不是班傑明不敢面對納粹的集中營,而是他以死來表達他對歷史的絕望。

美好樂園裡的集體遺忘|李中志

Perhaps the greatest scholar of Jewish mysticism in the twentieth century, Gershom Scholem (1897-1982) once said of himself, "I have no biography, only a bibliography." Yet, in thousands of letters written over his lifetime, his biography does unfold, inscribing a life that epitomized the intellectual ferment and political drama of an era. This selection of the best and most representative letters—drawn from the 3000 page German edition—gives readers an intimate view of this remarkable man, from his troubled family life in Germany to his emergence as one of the leading lights of Israel during its founding and formative years.

In the letters, we witness the travails and vicissitudes of the Scholem family, a drama in which Gershom is banished by his father for his anti-kaiser Zionist sentiments; his antiwar, socialist brother is hounded and murdered; and his mother and remaining brothers are forced to emigrate. We see Scholem’s friendships with some of the most intriguing intellectuals of the twentieth century—such as Hannah Arendt, Walter Benjamin, and Theodor Adorno—blossom and, on occasion, wither. And we learn firsthand about his Zionist commitment and his scholarly career, from his move to Palestine in the 1920s to his work as Professor of Jewish Mysticism at the Hebrew University. Over the course of seven decades that comprised the most significant events of the twentieth century, these letters reveal how Scholem’s scholarship is informed by the experiences he so eloquently described.

Introduction

I. A Jewish Zarathustra, 1914-1918

II. Unlocking the Gates, 1919-1932

III. Redemption through Sin, 1933-1947

IV. Master Magician Emeritus, 1948-1982

Notes

Selected Bibliography

Chronology

Index

I. A Jewish Zarathustra, 1914-1918

II. Unlocking the Gates, 1919-1932

III. Redemption through Sin, 1933-1947

IV. Master Magician Emeritus, 1948-1982

Notes

Selected Bibliography

Chronology

Index

“A biography of Gershom Scholem lies in these well selected and edited letters. Reading biographically between the letters’ lines, in the manner of Gershom Scholem, Master Scholar, you can learn how he found his own story between the lines of the Kabbalah’s texts he almost signlehandedly restored to life; and how he wrote his autobiography out so intensely, with such vast erudition and brilliance, in all his commentaries on the Kaballah that it became, over his lifetime, a biography of the whole endlessly resilient, culturally prolific Jewish people, a 20th century national epic.”—Elisabeth Young-Bruehl, author of Hannah Arendt: For Love of the World

“Scholem was a giant in the scholarly study of Jewish mysticism, responsible for bringing Kabbalah in particular to the attention of academia. However, the letters Skinner presents here reveal more of Scholem as a person than as a scholar. Scholem saw the two as intimately connected and would likely argue that these documents do aid in understanding his work. The decision to focus on the personal has the benefit of unearthing several firsthand accounts of critical events in 20th-century Jewish and European history.”—Stephen Joseph, Library Journal

“[Anthony David Skinner] has ably translated and edited a wide-ranging selection of letters from the life of this master scholar of Jewish mysticism. Most of the letters...appear here in English for the first time. [Skinner’s] selection illuminates a question that has always haunted readers of Scholem: How did the personality of this overly dignified and self-confident academic relate to the unbridled otherworldliness in the texts he analyzed with such seeming detachment?”—Publishers Weekly

“Gershom Scholem: A Life in Letters offers a fascinating sample of the 16,000 letters he exchanged with members of his family...His correspondences with brilliant intellectuals of his time make for fascinating reading and provide a close look at the thoughts, beliefs and passions of a man discovering Judaism in a time and place when it seemed to be disappearing...Anthony David Skinner had chosen the letters wisely and offers excellent overviews of the periods in which they were written.”—Sylvia Rothchild, Jewish Advocate

“A lively...collection, which follows Scholem from his fevered adolescence to the sovereign authority of his final years. The editor’s illuminating biographical summaries set out useful links from decade to decade, but it is Scholem’s uncompromising voice that gives this volume its unified force and striking crescendos. In their unstinting energy, the letters show a man exactly where he wanted to be, and conscious of exactly why.”—Cynthia Ozick, New Yorker

“Over seven decades, Scholem sent and received 16,000 letters. The Hebrew University’s Anthony David Skinner has lovingly translated and edited a selection of these...The replies--from such luminaries as Walter Benjamin, Martin Buber, Theodor Adorno and Hannah Arendt--create an engrossing dialogue. Skinner’s artful annotations render Scholem’s most esoteric notions accessible to the lay reader. And he shows how the adolescent maverick evolved from a "Jewish Zarathustra to Master Magician Emeritus of the post-war years"...It will whet readers’ appetites to read Scholem’s own books. In an age of emails and faxes, Scholem is truly a man of letters--in both senses of the term.”—Lawrence Joffe, Jewish Chronicle

“Anthony David Skinner has done a useful and meticulous job. This is the most readable history of German destruction and Israeli construction I know. And it describes Jewish habits of thought leading to this day and trailing back into the darkness over thousands of hidden years.”—Atar Hadari, Jewish Quarterly

“What can this lucky bookworm say to readers who are not especially curious about the kabbalah or about the history of universities in Israel? A great deal, as this selection of letters to and from Scholem makes clear. Some of its pleasures are simple ones: the spell-binding story of the Scholem clan...But this narrative also asks difficult questions: one is whether cleaving to a particular people and its tradition constitutes a self-imposed exile from a realm of more-universal concerns...[Skinner’s] translations, thankfully, let the correspondents speak in voices that sound like their own.”—The Economist

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia 部分

| Part of a series on |

| Kabbalah |

|---|

|

Scholem is best known for his collection of lectures, Major Trends in Jewish Mysticism (1941) and for his biography Sabbatai Zevi, the Mystical Messiah (1973). His collected speeches and essays, published as On Kabbalah and its Symbolism (1965), helped to spread knowledge of Jewish mysticism among non-Jews.

Contents |

Life

Gerhard Scholem was born in Berlin to Arthur Scholem and Betty Hirsch Scholem. His interest in Judaica was strongly opposed by his father, a printer, but, thanks to his mother's intervention, he was allowed to study Hebrew and the Talmud with an Orthodox rabbi.Gerhard Scholem met Walter Benjamin in Munich in 1915, when the former was seventeen years old and the latter was twenty-three. They began a lifelong friendship that ended only with Benjamin's suicide in 1940. In 1915 Scholem enrolled at the Humboldt University of Berlin, where he studied mathematics, philosophy, and Hebrew, and where he came into contact with Martin Buber, Shmuel Yosef Agnon, Hayim Nahman Bialik, Ahad Ha'am, and Zalman Shazar. In Berlin, he first befriended and became an admirer of Leo Strauss (their correspondence would continue throughout his life).[2] He subsequently studied mathematical logic at the University of Jena under Gottlob Frege. He was in Bern in 1918 with Benjamin when he met Elsa Burckhardt, who became his first wife. He returned to Germany in 1919, where he received a degree in semitic languages at the Ludwig Maximilians University of Munich. Less notable in his academic career was his establishment of the fictive University of Muri with Benjamin.

He wrote his doctoral thesis on the oldest known kabbalistic text, Sefer ha-Bahir. Drawn to Zionism, and influenced by Buber, he emigrated in 1923 to the British Mandate of Palestine, where he devoted his time to studying Jewish mysticism and became a librarian, and eventually head of the Department of Hebrew and Judaica at the National Library. He later became a lecturer at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

He taught the Kabbalah and mysticism from a scientific point of view and became the first professor of Jewish mysticism at the university in 1933, working in this post until his retirement in 1965, when he became an emeritus professor. In 1936, he married his second wife, Fania Freud.

Scholem's brother Werner was a member of the ultra-left "Fischer-Maslow Group" and the youngest ever member of the Reichstag, representing the Communist Party (KPD) in the German parliament. He was expelled from the party and later murdered by the Nazis during the Third Reich. Gershom Scholem, unlike his brother, was vehemently opposed to both Communism and Marxism.

Scholem died in Jerusalem, where he is buried next to his wife in Sanhedria. Jürgen Habermas delivered the eulogy.

Selected works in English

- Major Trends in Jewish Mysticism, 1941

- Jewish Gnosticism, Merkabah Mysticism, and the Talmudic Tradition, 1960

- Arendt and Scholem, "Eichmann in Jerusalem: Exchange of Letters between Gershom Scholem and Hannah Arendt", in Encounter, 22/1, 1964

- The Messianic Idea in Judaism and other Essays on Jewish Spirituality, trans. 1971

- Sabbatai Sevi: The Mystical Messiah, 1973

- From Berlin to Jerusalem: Memories of My Youth, trans. Harry Zohn, 1980.

- 從柏林到耶路撒冷

作者:[以]格舒姆·索羅姆

出版:漓江出版社

2015年版

最不平凡時代的青少年歲月,鑄就最具影響力的猶太思想家。格舒姆·索羅姆被譽為20世紀最為深刻的猶太哲學家。“索羅姆具備那種最罕見的精神人格……他同時是哲學家、社會歷史學家、睿智雄健的論說文作家,而在此之上,還有一份良知——這苦難、險惡、兇殘的人世並不乏對這良知的了解,卻又總是忽視它的存在……”本書是其早年求知生涯的回憶錄,記敘了作者童年至青少年時期的人生經歷。

- Kabbalah, Meridian 1974, Plume Books 1987 reissue: ISBN 0-452-01007-1

- Walter Benjamin: the Story of a Friendship, trans. Harry Zohn. New York: Schocken Books, 1981.

- Origins of the Kabbalah, JPS, 1987 reissue: ISBN 0-691-02047-7

- On the Mystical Shape of the Godhead: Basic Concepts in the Kabbalah, 1997

- The Fullness of Time: Poems, trans. Richard Sieburth

- On Jews and Judaism in Crisis: Selected Essays

- On the Kabbalah and Its Symbolism

- Tselem: The Representation of the Astral Body, trans. Scott J. Thompson 1987

- Zohar — The Book of Splendor: Basic Readings from the Kabbalah, ed.

ゲルショム・ゲルハルト・ショーレム(גרשם גרהרד שלוםGershom Gerhard Scholem1897年12月5日 - 1982年2月21日)はドイツ生まれのイスラエルの思想家。ユダヤ神秘主義(カバラ)の世界的権威で、ヘブライ大学教授を務めた。1958年にイスラエル賞を受賞。1968年にはイスラエル文理学士院の院長に選ばれた。

彼はベルリンでユダヤ人の家庭に生まれ育った。父はアルトゥール・ショーレム、母はベティ・ヒルシュ・ショーレム。画家だった父は同化主義者で、息子がユダヤ教に興味を持つのを喜ばなかったが、ショーレムは母のとりなしにより正統派のラビのもとでヘブライ語やタルムードを学ぶことを許された。

ベルリン大学で数学と哲学とヘブライ語を専攻。大学では、マルティーン・ブーバーやヴァルター・ベンヤミン、シュムエル・ヨセフ・アグノン、ハイム・ナフマン・ビアーリク、アハッド・ハーアム、ザルマン・シャザールといった面々と知り合った。1918年にはベンヤミンと共にスイスのベルンにいたが、ここで最初の妻エルザ・ブルクハルトを識った。1919年にドイツへ戻り、ミュンヘン大学からセム語研究で学位を受けた。

博士論文のテーマは、最古のカバラ文献סֵפֶר הַבָּהִיר(セフェル・ハ=バヒール; "光輝の書")だった。シオニズムに傾倒し、友人ブーバーの影響もあって、1923年に英領パレスチナへ移住。ここで彼はユダヤ神秘主義の研究に没頭し、司書の職を得た。最終的にはイスラエル国会図書館のヘブライ・ユダヤ文献部門の責任者となった。のちにエルサレムのヘブライ大学で、講師として教え始めた。

彼の特色は、自然科学の素養を活かして、カバラを科学的に教えた点にある。1933年にはヘブライ大学のユダヤ神秘主義講座の初代教授に就任、1965年に名誉教授となるまでこの地位にあった。ユング等が関わった「エラノス会議」にも参加

1936年、ファニア・フロイトと再婚。

兄のヴェルナー・ショーレムはドイツの極左組織<フィッシャー=マスロフ団>の一員で、ドイツ帝国議会ではドイツ共産党選出の議員だったが、のちに議会から追放され、ナチによって暗殺された。

邦訳著書[編集]

- 『ユダヤ主義の本質』 河出書房新社, 1972年

- 『ユダヤ主義と西欧』 河出書房新社, 1973年

- 『ユダヤ教神秘主義』 河出書房新社, 1975年

- 『わが友ベンヤミン』 晶文社, 1978年

- 『ユダヤ神秘主義』 叢書ウニベルシタス・法政大学出版局, 1985年 別訳

- 『カバラとその象徴的表現』 叢書ウニベルシタス・法政大学出版局, 1985年

- 『ベンヤミンーショーレム往復書簡』 叢書ウニベルシタス・法政大学出版局, 1990年

- 『ベルリンからエルサレムへ 青春の思い出』 叢書ウニベルシタス・法政大学出版局, 1991年

- 『錬金術とカバラ』 作品社, 2001年

- 『サバタイ・ツヴィ伝 神秘のメシア』 2冊組 叢書ウニベルシタス・法政大学出版, 2009年

- 『エラノス叢書』 平凡社全9巻別冊1、1994-95年、数編の論文が所収。

Arendt and Scholem, "Eichmann in Jerusalem: Exchange of Letters between Gershom Scholem and Hannah Arendt", in Encounter, 22/1, 1964

The Messianic Idea in Judaism and other Essays on Jewish Spirituality, trans. 1971

Sabbatai Sevi: The Mystical Messiah, 1973

The Messianic Idea in Judaism and other Essays on Jewish Spirituality, trans. 1971

Sabbatai Sevi: The Mystical Messiah, 1973

From Berlin to Jerusalem: Memories of My Youth, trans. Harry Zohn, 1980.

從柏林到耶路撒冷

作者:[以]格舒姆·索羅姆

出版:漓江出版社

2015年版

最不平凡時代的青少年歲月,鑄就最具影響力的猶太思想家。格舒姆·索羅姆被譽為20世紀最為深刻的猶太哲學家。“索羅姆具備那種最罕見的精神人格……他同時是哲學家、社會歷史學家、睿智雄健的論說文作家,而在此之上,還有一份良知——這苦難、險惡、兇殘的人世並不乏對這良知的了解,卻又總是忽視它的存在……”本書是其早年求知生涯的回憶錄,記敘了作者童年至青少年時期的人生經歷。

從柏林到耶路撒冷

作者:[以]格舒姆·索羅姆

出版:漓江出版社

2015年版

最不平凡時代的青少年歲月,鑄就最具影響力的猶太思想家。格舒姆·索羅姆被譽為20世紀最為深刻的猶太哲學家。“索羅姆具備那種最罕見的精神人格……他同時是哲學家、社會歷史學家、睿智雄健的論說文作家,而在此之上,還有一份良知——這苦難、險惡、兇殘的人世並不乏對這良知的了解,卻又總是忽視它的存在……”本書是其早年求知生涯的回憶錄,記敘了作者童年至青少年時期的人生經歷。

----

因為受到I. Berlin等人對於 Hannah Arendt的評價 對她的作品比較少涉獵. 不過其作品不少有漢譯了.

Gershom Scholem A Life in Letters, 1914-1982 , pp.393-98 有兩人對於 “Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil,”一書的許多不同的見解 包括 “the banality of evil.” 是否只是一口號.http://hcbooks.blogspot.tw/…/gershom-scholem-life-in-letter…

因為受到I. Berlin等人對於 Hannah Arendt的評價 對她的作品比較少涉獵. 不過其作品不少有漢譯了.

Gershom Scholem A Life in Letters, 1914-1982 , pp.393-98 有兩人對於 “Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil,”一書的許多不同的見解 包括 “the banality of evil.” 是否只是一口號.http://hcbooks.blogspot.tw/…/gershom-scholem-life-in-letter…