There were three Lewises. The first was the distinguished Oxford don who seemed to have read everything and to have remembered it all. The second Lewis was the former atheist and Christian apologist. Finally, there was the author of bestselling popular novels

C. S. Lewis Reviews The Hobbit, 1937

November 19, 2013 | by C.S. Lewis

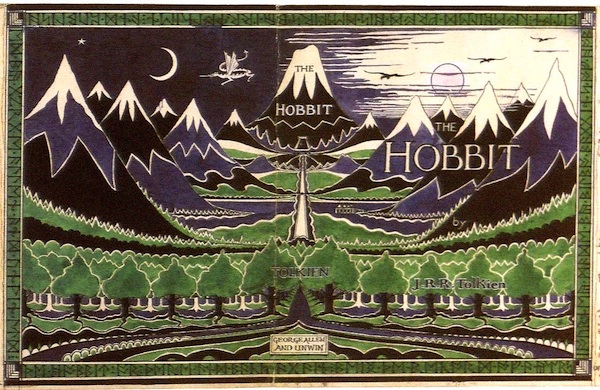

A world for children: J. R. R. Tolkien,

The Hobbit: or There and Back Again

(London: Allen and Unwin, 1937)

The publishers claim that The Hobbit, though very unlike Alice, resembles it in being the work of a professor at play. A more important truth is that both belong to a very small class of books which have nothing in common save that each admits us to a world of its own—a world that seems to have been going on long before we stumbled into it but which, once found by the right reader, becomes indispensable to him. Its place is with Alice, Flatland, Phantastes, The Wind in the Willows. [1]

To define the world of The Hobbit is, of course, impossible, because it is new. You cannot anticipate it before you go there, as you cannot forget it once you have gone. The author’s admirable illustrations and maps of Mirkwood and Goblingate and Esgaroth give one an inkling—and so do the names of the dwarf and dragon that catch our eyes as we first ruffle the pages. But there are dwarfs and dwarfs, and no common recipe for children’s stories will give you creatures so rooted in their own soil and history as those of Professor Tolkien—who obviously knows much more about them than he needs for this tale. Still less will the common recipe prepare us for the curious shift from the matter-of-fact beginnings of his story (“hobbits are small people, smaller than dwarfs—and they have no beards—but very much larger than Lilliputians”) [2] to the saga-like tone of the later chapters (“It is in my mind to ask what share of their inheritance you would have paid to our kindred had you found the hoard unguarded and us slain”). [3] You must read for yourself to find out how inevitable the change is and how it keeps pace with the hero’s journey. Though all is marvellous, nothing is arbitrary: all the inhabitants of Wilderland seem to have the same unquestionable right to their existence as those of our own world, though the fortunate child who meets them will have no notion—and his unlearned elders not much more—of the deep sources in our blood and tradition from which they spring.

For it must be understood that this is a children’s book only in the sense that the first of many readings can be undertaken in the nursery. Alice is read gravely by children and with laughter by grown ups; The Hobbit, on the other hand, will be funnier to its youngest readers, and only years later, at a tenth or a twentieth reading, will they begin to realise what deft scholarship and profound reflection have gone to make everything in it so ripe, so friendly, and in its own way so true. Prediction is dangerous: but The Hobbit may well prove a classic.

Review published in the Times Literary Supplement (2 October 1937), 714.

1. Flatland (1884) is by Edwin A. Abbott, Phantastes by George MacDonald (1858).

2. The Hobbit: or There and Back Again (1937), chapter 1.

3. Ibid., chapter 15.

Image and Imagination: Essays and Reviews, by C. S. Lewis, edited by Walter Hooper. Copyright © 2013 C. S. Lewis Pte Ltd. Reprinted with the permission of Cambridge University Press.

This article originally appeared in the Times Literary Supplement. Click here to read it on the TLS site.

Tolkien's myths are a political fantasy

In a world built on myth, we can’t ignore the reactionary politics at the heart of Tolkien’s Middle Earth

It’s a double-edged magical sword, being a fan of JRR Tolkien. On one hand we’ve had the joy of watching Lord of the Rings go from cult success to, arguably, the most successful and influential story of the last century. And we get to laugh in the face of critics who claimed LotR would never amount to anything, while watching a sumptuous (if absurdly long) adaption of The Hobbit.

On the other hand, you also have to consider the serious criticisms made of Tolkien’s writing, such as Michael Moorcock’s in his 1978 essay, Epic Pooh. As a storyteller Tolkien is on a par with Homer or the anonymous bard behind Beowulf, the epic poets who so influenced his work. But as works of modern mythology, the art Tolkien called “mythopoeia”, both Lord of the Rings and The Hobbit are open to serious criticism.

To understand why takes a little consideration of what we really mean by the word “myth”. The world can be a bafflingly complex place. Why is the sky blue? What’s this rocky stuff I’m standing on? Who are all these hairless chimps I’m surrounded by? The only way we don’t just keep babbling endless questions like hyperactive six-year-olds is by reducing the infinite complexities of existence to something more simple. To a story. Stories that we call myths.

Myths are a lens through which we investigate the mysteries of the world around us. Change the myth, and you can change the world – as JRR Tolkien well knew when, alongside other writers including CS Lewis, he began to consider the possibility of creating new myths to help us better understand the modern world – or if not to understand it better, then to understand it differently. Tolkien borrowed the Greek term “mythpoesis” to describe the task of modern myth-making, and so the literary concept of mythopoeia was born.Science gives us far more accurate answers to our questions than ever before. But we’re still dependent on myths to actually comprehend the science. The multi-dimensional expansion of energy, space and time we call the Big Bang wasn’t literally a bang any more than God saying “Let there be light” was literally how the universe was created. They’re both mythic ideas that point at an actual truth our mammalian minds aren’t equipped to grasp.

Tolkien’s myths are profoundly conservative. Both The Hobbit and Lord of the Rings turn on the “return of the king” to his rightful throne. In both cases this “victory” means the reassertion of a feudal social structure which had been disrupted by “evil”. Both books are one-sided recollections made the Baggins family, members of the landed gentry, in the Red Book of Westmarch – an unreliable historical source if ever there was one. A balanced telling might well have shown Smaug to be much more of a reforming force in the valley of Dale.

And of course Sauron doesn’t even get to appear on the page in The Lord of the Rings, at least not in any form more substantial than a huge burning eye, exactly the kind of treatment one would expect in a work of propaganda.

We’re left to take on trust from Gandalf, a manipulative spin doctor, and the Elves, immortal elitists who kill humans and hobbits for even entering their territory, when they say that the maker of the one ring is evil. Isn’t it more likely that the orcs, who live in dire poverty, actually support Sauron because he represents the liberal forces of science and industrialisation, in the face of a brutally oppressive conservative social order?

Whatever the limitations of his own myth-making, Tolkien’s genius as a storyteller rekindled the flame of mythopoeia for generations of writers who followed. Today our bookshelves and cinema screens are once again heaving with modern myths. And they represent a vastly diverse spectrum of worldviews, from the authoritarian fantasy of Orson Scott Card’s Enders Game, to the anti-capitalist metaphor of The Hunger Games. The latter is so potent that the three-finger salute given by Katniss Everdeen has become a symbol of freedom. What clearer sign could there be that the contemporary world is still powered by myth?The Hobbit and Lord of the Rings aren’t fantasies because they feature dragons, elves and talking trees. They’re fantasies because they mythologise human history, ignoring the brutality and oppression that were part and parcel of a world ruled by men with swords. But we shouldn’t be surprised that the wish to return to a more conservative society, one where people knew their place is so popular. It’s the same myth that conservative political parties such as Ukip have always played on: the myth of a better world that has been lost, but can be reclaimed by turning back the clock.