Everyman's Library

"Solitude" by Anna Akhmatova

So many stones have been thrown at me,

That I'm not frightened of them anymore,

And the pit has become a solid tower,

Tall among tall towers.

I thank the builders,

May care and sadness pass them by.

From here I'll see the sunrise earlier,

Here the sun's last ray rejoices.

And into the windows of my room

The northern breezes often fly.

And from my hand a dove eats grains of wheat...

As for my unfinished page,

The Muse's tawny hand, divinely calm

And delicate, will finish it.

*

"Everything" by Anna Akhmatova

Everything’s looted, betrayed and traded,

black death’s wing’s overhead.

Everything’s eaten by hunger, unsated,

so why does a light shine ahead?

black death’s wing’s overhead.

Everything’s eaten by hunger, unsated,

so why does a light shine ahead?

By day, a mysterious wood, near the town,

breathes out cherry, a cherry perfume.

By night, on July’s sky, deep, and transparent,

new constellations are thrown.

breathes out cherry, a cherry perfume.

By night, on July’s sky, deep, and transparent,

new constellations are thrown.

And something miraculous will come

close to the darkness and ruin,

something no-one, no-one, has known,

though we’ve longed for it since we were children.

close to the darkness and ruin,

something no-one, no-one, has known,

though we’ve longed for it since we were children.

*

A legend in her own time both for her brilliant poetry and for her resistance to oppression, Anna Akhmatova—denounced by the Soviet regime for her “eroticism, mysticism, and political indifference”—is one of the greatest Russian poets of the twentieth century. Before the revolution, Akhmatova was a wildly popular young poet who lived a bohemian life. She was one of the leaders of a movement of poets whose ideal was “beautiful clarity”—in her deeply personal work, themes of love and mourning are conveyed with passionate intensity and economy, her voice by turns tender and fierce. A vocal critic of Stalinism, she saw her work banned for many years and was expelled from the Writers’ Union—condemned as “half nun, half harlot.” Despite this censorship, her reputation continued to flourish underground, and she is still among Russia’s most beloved poets. Here are poems from all her major works—including the magnificent “Requiem” commemorating the victims of Stalin’s terror—and some that have been newly translated for this edition.

櫻桃園文化出版社分享了 РИА Новости 的相片。

今天是俄國女詩人安娜‧阿赫瑪托娃(1889-1966)的125歲誕辰。

阿赫瑪托娃極愛普希金與杜斯妥也夫斯基,並在筆記裡說過:杜斯妥也夫斯基解開了普希金的謎。

而阿赫瑪托娃自己呢,彷彿也試圖用詩歌創作來解開杜斯妥也夫斯基的小說世界──這就是俄羅斯的心靈世界。

阿赫瑪托娃極愛普希金與杜斯妥也夫斯基,並在筆記裡說過:杜斯妥也夫斯基解開了普希金的謎。

而阿赫瑪托娃自己呢,彷彿也試圖用詩歌創作來解開杜斯妥也夫斯基的小說世界──這就是俄羅斯的心靈世界。

В этот день 125 лет назад родилась одна из известнейших русских поэтесс XX века Анна Ахматова. Уже к 1920-м годам она стала признанным классиком отечественной п⋯⋯更多

這一天,125 年前出生在二十世紀,安娜 · 阿赫瑪最著名的俄羅斯詩人之一。早在 1920 年她成為了公認的經典的愛國詩歌,但即使他死後,阿赫瑪遭受了嚴重的審查制度。她的許多作品不超過二十年,在她死後發表。 (翻譯由 Bing 提供)

Robin與我談他對於文字翻譯的高標準要求,我心有戚戚。

安娜·安德烈耶芙娜·艾哈邁托娃(А́нна Ахма́това,1889年6月23日-1966年3月5日),俄羅斯「白銀時代」的代表性詩人。阿赫瑪托娃為筆名,原名是「安娜·安德烈耶芙娜·戈連科」(А́нна Андре́евна Гóренко)。在百姓心中,她被譽為「俄羅斯詩歌的月亮」(普希金曾被譽為「俄羅斯詩歌的太陽」);在蘇聯政府的嘴裡,她卻被污衊為「蕩婦兼修女」。

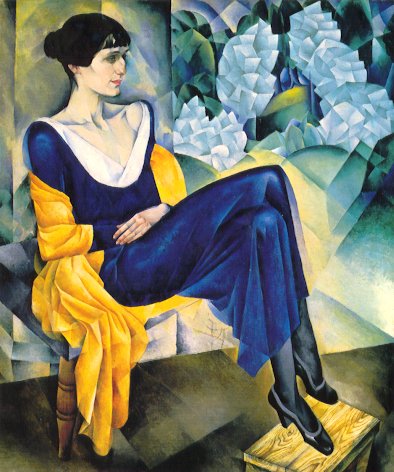

Portrait by Nathan Altman of Anna Akhmatova, 1914 © below

The poet Anna Akhmatova was born Anna Gorenko in Odessa, in the Ukraine, in 1889; she later changed her name to Akhmtova. In 1910 she married the important Russian poet and theorist Nikolai Gumilyov. Shortly afterwards Akhmatova began publishing her own poetry; together with Gumilyov, she became a central figure in the Acmeist movement. Acmeism -- which had its parallels in the writings of T. E. Hulme in England and the development of Imagism -- stressed clarity and craft as antidotes to the overly loose style and vague language of late nineteenth century poetry in Russia.

The poet Anna Akhmatova was born Anna Gorenko in Odessa, in the Ukraine, in 1889; she later changed her name to Akhmtova. In 1910 she married the important Russian poet and theorist Nikolai Gumilyov. Shortly afterwards Akhmatova began publishing her own poetry; together with Gumilyov, she became a central figure in the Acmeist movement. Acmeism -- which had its parallels in the writings of T. E. Hulme in England and the development of Imagism -- stressed clarity and craft as antidotes to the overly loose style and vague language of late nineteenth century poetry in Russia.The Russian Revolution was to dramatically affect their lives. Although they had recently divorced, Akhmatova was was nevertheless stunned by the execution of her friend and former partner Gumilyev in 1921 by the Bolsheviks, who claimed that he had betrayed the Revolution. In large measure to drive her into silence, their son Lev Gumilyov was imprisoned in 1938, and he remained in prison and prison camps until the death of Stalin and the thaw in the Cold War made his release possible in 1956. Meanwhile, Akhmatova had a second marraige and then a third; her third husband, Nikolai Punin, was imprisoned in 1949 and thereafter died in 1953 in a Siberian prison camp. Her writing was banned, unofficially, from 1925 to 1940, and then was banned again after World War Two was concluded. Unlike many of her literary contemporaries, though, she never considered flight into exile.

Persecuted by the Stalinist government, prevented from publishing, regarded as a dangerous enemy , but at the same time so popular on the basis of her early poetry that even Stalin would not risk attacking her directly, Akhmatova's life was hard. Her greatest poem, "Requiem," recounts the suffering of the Russian people under Stalinism -- specifically, the tribulations of those women with whom Akhmatova stood in line outside the prison walls, women who like her waited patiently, but with a sense of great grief and powerlessness, for the chance to send a loaf of bread or a small message to their husbands, sons, lovers. It was not published in in Russia in its entirety until 1987, though the poem itself was begun about the time of her son's arrest. It was his arrest and imprisonment, and the later arrest of her husband Punin, that provided the occasion for the specific content of the poem, which is sequence of lyric poems about imprisonment and its affect on those whose loveed ones are arrested, sentenced, and incarcerated behing prison walls..

The poet was awarded and honorary doctorate by Oxford University in 1965. Akhmatova died in 1966 in Leningrad.

Akhmatova Links:

- If you'd like to hear Anna Akhmatova read a brief Russian poem IN RUSSIAN, go to Russian Poem and click on the .wav file format 935K, and shortly you will her her read! This page also has many links to other Akhmatova sites, and a brief anthology of her poetry.

- For a brief biography of the poet, go to Biography.

- For another brief biography, and a list of her works translated into English, go to the Academy of American Poets' page on Akhmatova at AAP page.

- Translations of a number of Akhmatova's poems can be found at Translations

- Several translations by one of the two best translators (D.M. Thomas -- tthe other great translation is the collaborative work of U.S. Poet Laureate Stanley Kunitz and Max Haward) and annotated links can be found at Thomas translations

- A page with almost twenty translations and a brief essay. What is notable about this page is that it is part of a series -- which can easily be accessed from the right column of this page -- on a multitude of Russian writers, inclduing Akhmatova's friends/contemporaries Gumilev, Pasternak, Mandelshtam, and Tsvetaeva. Click on Akhmatova, and her Russian contemporaries

Anna Akhmatova's Other Poems

Requiem

Not under foreign skies

Nor under foreign wings protected -

I shared all this with my own people

There, where misfortune had abandoned us.

[1961]

INSTEAD OF A PREFACE

During the frightening years of the Yezhov terror, I

spent seventeen months waiting in prison queues in

Leningrad. One day, somehow, someone 'picked me out'.

On that occasion there was a woman standing behind me,

her lips blue with cold, who, of course, had never in

her life heard my name. Jolted out of the torpor

characteristic of all of us, she said into my ear

(everyone whispered there) - 'Could one ever describe

this?' And I answered - 'I can.' It was then that

something like a smile slid across what had previously

been just a face.

[The 1st of April in the year 1957. Leningrad]

DEDICATION

Mountains fall before this grief,

A mighty river stops its flow,

But prison doors stay firmly bolted

Shutting off the convict burrows

And an anguish close to death.

Fresh winds softly blow for someone,

Gentle sunsets warm them through; we don't know this,

We are everywhere the same, listening

To the scrape and turn of hateful keys

And the heavy tread of marching soldiers.

Waking early, as if for early mass,

Walking through the capital run wild, gone to seed,

We'd meet - the dead, lifeless; the sun,

Lower every day; the Neva, mistier:

But hope still sings forever in the distance.

The verdict. Immediately a flood of tears,

Followed by a total isolation,

As if a beating heart is painfully ripped out, or,

Thumped, she lies there brutally laid out,

But she still manages to walk, hesitantly, alone.

Where are you, my unwilling friends,

Captives of my two satanic years?

What miracle do you see in a Siberian blizzard?

What shimmering mirage around the circle of the moon?

I send each one of you my salutation, and farewell.

[March 1940]

INTRODUCTION

[PRELUDE]

It happened like this when only the dead

Were smiling, glad of their release,

That Leningrad hung around its prisons

Like a worthless emblem, flapping its piece.

Shrill and sharp, the steam-whistles sang

Short songs of farewell

To the ranks of convicted, demented by suffering,

As they, in regiments, walked along -

Stars of death stood over us

As innocent Russia squirmed

Under the blood-spattered boots and tyres

Of the black marias.

I

You were taken away at dawn. I followed you

As one does when a corpse is being removed.

Children were crying in the darkened house.

A candle flared, illuminating the Mother of God. . .

The cold of an icon was on your lips, a death-cold

sweat

On your brow - I will never forget this; I will gather

To wail with the wives of the murdered streltsy (1)

Inconsolably, beneath the Kremlin towers.

[1935. Autumn. Moscow]

II

Silent flows the river Don

A yellow moon looks quietly on

Swanking about, with cap askew

It sees through the window a shadow of you

Gravely ill, all alone

The moon sees a woman lying at home

Her son is in jail, her husband is dead

Say a prayer for her instead.

III

It isn't me, someone else is suffering. I couldn't.

Not like this. Everything that has happened,

Cover it with a black cloth,

Then let the torches be removed. . .

Night.

IV

Giggling, poking fun, everyone's darling,

The carefree sinner of Tsarskoye Selo (2)

If only you could have foreseen

What life would do with you -

That you would stand, parcel in hand,

Beneath the Crosses (3), three hundredth in

line,

Burning the new year's ice

With your hot tears.

Back and forth the prison poplar sways

With not a sound - how many innocent

Blameless lives are being taken away. . .

[1938]

V

For seventeen months I have been screaming,

Calling you home.

I've thrown myself at the feet of butchers

For you, my son and my horror.

Everything has become muddled forever -

I can no longer distinguish

Who is an animal, who a person, and how long

The wait can be for an execution.

There are now only dusty flowers,

The chinking of the thurible,

Tracks from somewhere into nowhere

And, staring me in the face

And threatening me with swift annihilation,

An enormous star.

[1939]

VI

Weeks fly lightly by. Even so,

I cannot understand what has arisen,

How, my son, into your prison

White nights stare so brilliantly.

Now once more they burn,

Eyes that focus like a hawk,

And, upon your cross, the talk

Is again of death.

[1939. Spring]

VII

THE VERDICT

The word landed with a stony thud

Onto my still-beating breast.

Nevermind, I was prepared,

I will manage with the rest.

I have a lot of work to do today;

I need to slaughter memory,

Turn my living soul to stone

Then teach myself to live again. . .

But how. The hot summer rustles

Like a carnival outside my window;

I have long had this premonition

Of a bright day and a deserted house.

[22 June 1939. Summer. Fontannyi Dom (4)]

VIII

TO DEATH

You will come anyway - so why not now?

I wait for you; things have become too hard.

I have turned out the lights and opened the door

For you, so simple and so wonderful.

Assume whatever shape you wish. Burst in

Like a shell of noxious gas. Creep up on me

Like a practised bandit with a heavy weapon.

Poison me, if you want, with a typhoid exhalation,

Or, with a simple tale prepared by you

(And known by all to the point of nausea), take me

Before the commander of the blue caps and let me

glimpse

The house administrator's terrified white face.

I don't care anymore. The river Yenisey

Swirls on. The Pole star blazes.

The blue sparks of those much-loved eyes

Close over and cover the final horror.

[19 August 1939. Fontannyi Dom]

IX

Madness with its wings

Has covered half my soul

It feeds me fiery wine

And lures me into the abyss.

That's when I understood

While listening to my alien delirium

That I must hand the victory

To it.

However much I nag

However much I beg

It will not let me take

One single thing away:

Not my son's frightening eyes -

A suffering set in stone,

Or prison visiting hours

Or days that end in storms

Nor the sweet coolness of a hand

The anxious shade of lime trees

Nor the light distant sound

Of final comforting words.

[14 May 1940. Fontannyi Dom]

X

CRUCIFIXION

Weep not for me, mother.

I am alive in my grave.

1.

A choir of angels glorified the greatest hour,

The heavens melted into flames.

To his father he said, 'Why hast thou forsaken me!'

But to his mother, 'Weep not for me. . .'

[1940. Fontannyi Dom]

2.

Magdalena smote herself and wept,

The favourite disciple turned to stone,

But there, where the mother stood silent,

Not one person dared to look.

[1943. Tashkent]

EPILOGUE

1.

I have learned how faces fall,

How terror can escape from lowered eyes,

How suffering can etch cruel pages

Of cuneiform-like marks upon the cheeks.

I know how dark or ash-blond strands of hair

Can suddenly turn white. I've learned to recognise

The fading smiles upon submissive lips,

The trembling fear inside a hollow laugh.

That's why I pray not for myself

But all of you who stood there with me

Through fiercest cold and scorching July heat

Under a towering, completely blind red wall.

2.

The hour has come to remember the dead.

I see you, I hear you, I feel you:

The one who resisted the long drag to the open window;

The one who could no longer feel the kick of familiar

soil beneath her feet;

The one who, with a sudden flick of her head, replied,

'I arrive here as if I've come home!'

I'd like to name you all by name, but the list

Has been removed and there is nowhere else to look.

So,

I have woven you this wide shroud out of the humble

words

I overheard you use. Everywhere, forever and always,

I will never forget one single thing. Even in new

grief.

Even if they clamp shut my tormented mouth

Through which one hundred million people scream;

That's how I wish them to remember me when I am dead

On the eve of my remembrance day.

If someone someday in this country

Decides to raise a memorial to me,

I give my consent to this festivity

But only on this condition - do not build it

By the sea where I was born,

I have severed my last ties with the sea;

Nor in the Tsar's Park by the hallowed stump

Where an inconsolable shadow looks for me;

Build it here where I stood for three hundred hours

And no-one slid open the bolt.

Listen, even in blissful death I fear

That I will forget the Black Marias,

Forget how hatefully the door slammed and an old woman

Howled like a wounded beast.

Let the thawing ice flow like tears

From my immovable bronze eyelids

And let the prison dove coo in the distance

While ships sail quietly along the river.

[March 1940. Fontannyi Dom]

FOOTNOTES

1 An elite guard which rose up in rebellion

against Peter the Great in 1698. Most were either

executed or exiled.

2 The imperial summer residence outside St

Petersburg where Ahmatova spent her early years.

3 A prison complex in central Leningrad near the

Finland Station, called The Crosses because of the

shape of two of the buildings.

4 The Leningrad house in which Ahmatova lived.

Nor under foreign wings protected -

I shared all this with my own people

There, where misfortune had abandoned us.

[1961]

INSTEAD OF A PREFACE

During the frightening years of the Yezhov terror, I

spent seventeen months waiting in prison queues in

Leningrad. One day, somehow, someone 'picked me out'.

On that occasion there was a woman standing behind me,

her lips blue with cold, who, of course, had never in

her life heard my name. Jolted out of the torpor

characteristic of all of us, she said into my ear

(everyone whispered there) - 'Could one ever describe

this?' And I answered - 'I can.' It was then that

something like a smile slid across what had previously

been just a face.

[The 1st of April in the year 1957. Leningrad]

DEDICATION

Mountains fall before this grief,

A mighty river stops its flow,

But prison doors stay firmly bolted

Shutting off the convict burrows

And an anguish close to death.

Fresh winds softly blow for someone,

Gentle sunsets warm them through; we don't know this,

We are everywhere the same, listening

To the scrape and turn of hateful keys

And the heavy tread of marching soldiers.

Waking early, as if for early mass,

Walking through the capital run wild, gone to seed,

We'd meet - the dead, lifeless; the sun,

Lower every day; the Neva, mistier:

But hope still sings forever in the distance.

The verdict. Immediately a flood of tears,

Followed by a total isolation,

As if a beating heart is painfully ripped out, or,

Thumped, she lies there brutally laid out,

But she still manages to walk, hesitantly, alone.

Where are you, my unwilling friends,

Captives of my two satanic years?

What miracle do you see in a Siberian blizzard?

What shimmering mirage around the circle of the moon?

I send each one of you my salutation, and farewell.

[March 1940]

INTRODUCTION

[PRELUDE]

It happened like this when only the dead

Were smiling, glad of their release,

That Leningrad hung around its prisons

Like a worthless emblem, flapping its piece.

Shrill and sharp, the steam-whistles sang

Short songs of farewell

To the ranks of convicted, demented by suffering,

As they, in regiments, walked along -

Stars of death stood over us

As innocent Russia squirmed

Under the blood-spattered boots and tyres

Of the black marias.

I

You were taken away at dawn. I followed you

As one does when a corpse is being removed.

Children were crying in the darkened house.

A candle flared, illuminating the Mother of God. . .

The cold of an icon was on your lips, a death-cold

sweat

On your brow - I will never forget this; I will gather

To wail with the wives of the murdered streltsy (1)

Inconsolably, beneath the Kremlin towers.

[1935. Autumn. Moscow]

II

Silent flows the river Don

A yellow moon looks quietly on

Swanking about, with cap askew

It sees through the window a shadow of you

Gravely ill, all alone

The moon sees a woman lying at home

Her son is in jail, her husband is dead

Say a prayer for her instead.

III

It isn't me, someone else is suffering. I couldn't.

Not like this. Everything that has happened,

Cover it with a black cloth,

Then let the torches be removed. . .

Night.

IV

Giggling, poking fun, everyone's darling,

The carefree sinner of Tsarskoye Selo (2)

If only you could have foreseen

What life would do with you -

That you would stand, parcel in hand,

Beneath the Crosses (3), three hundredth in

line,

Burning the new year's ice

With your hot tears.

Back and forth the prison poplar sways

With not a sound - how many innocent

Blameless lives are being taken away. . .

[1938]

V

For seventeen months I have been screaming,

Calling you home.

I've thrown myself at the feet of butchers

For you, my son and my horror.

Everything has become muddled forever -

I can no longer distinguish

Who is an animal, who a person, and how long

The wait can be for an execution.

There are now only dusty flowers,

The chinking of the thurible,

Tracks from somewhere into nowhere

And, staring me in the face

And threatening me with swift annihilation,

An enormous star.

[1939]

VI

Weeks fly lightly by. Even so,

I cannot understand what has arisen,

How, my son, into your prison

White nights stare so brilliantly.

Now once more they burn,

Eyes that focus like a hawk,

And, upon your cross, the talk

Is again of death.

[1939. Spring]

VII

THE VERDICT

The word landed with a stony thud

Onto my still-beating breast.

Nevermind, I was prepared,

I will manage with the rest.

I have a lot of work to do today;

I need to slaughter memory,

Turn my living soul to stone

Then teach myself to live again. . .

But how. The hot summer rustles

Like a carnival outside my window;

I have long had this premonition

Of a bright day and a deserted house.

[22 June 1939. Summer. Fontannyi Dom (4)]

VIII

TO DEATH

You will come anyway - so why not now?

I wait for you; things have become too hard.

I have turned out the lights and opened the door

For you, so simple and so wonderful.

Assume whatever shape you wish. Burst in

Like a shell of noxious gas. Creep up on me

Like a practised bandit with a heavy weapon.

Poison me, if you want, with a typhoid exhalation,

Or, with a simple tale prepared by you

(And known by all to the point of nausea), take me

Before the commander of the blue caps and let me

glimpse

The house administrator's terrified white face.

I don't care anymore. The river Yenisey

Swirls on. The Pole star blazes.

The blue sparks of those much-loved eyes

Close over and cover the final horror.

[19 August 1939. Fontannyi Dom]

IX

Madness with its wings

Has covered half my soul

It feeds me fiery wine

And lures me into the abyss.

That's when I understood

While listening to my alien delirium

That I must hand the victory

To it.

However much I nag

However much I beg

It will not let me take

One single thing away:

Not my son's frightening eyes -

A suffering set in stone,

Or prison visiting hours

Or days that end in storms

Nor the sweet coolness of a hand

The anxious shade of lime trees

Nor the light distant sound

Of final comforting words.

[14 May 1940. Fontannyi Dom]

X

CRUCIFIXION

Weep not for me, mother.

I am alive in my grave.

1.

A choir of angels glorified the greatest hour,

The heavens melted into flames.

To his father he said, 'Why hast thou forsaken me!'

But to his mother, 'Weep not for me. . .'

[1940. Fontannyi Dom]

2.

Magdalena smote herself and wept,

The favourite disciple turned to stone,

But there, where the mother stood silent,

Not one person dared to look.

[1943. Tashkent]

EPILOGUE

1.

I have learned how faces fall,

How terror can escape from lowered eyes,

How suffering can etch cruel pages

Of cuneiform-like marks upon the cheeks.

I know how dark or ash-blond strands of hair

Can suddenly turn white. I've learned to recognise

The fading smiles upon submissive lips,

The trembling fear inside a hollow laugh.

That's why I pray not for myself

But all of you who stood there with me

Through fiercest cold and scorching July heat

Under a towering, completely blind red wall.

2.

The hour has come to remember the dead.

I see you, I hear you, I feel you:

The one who resisted the long drag to the open window;

The one who could no longer feel the kick of familiar

soil beneath her feet;

The one who, with a sudden flick of her head, replied,

'I arrive here as if I've come home!'

I'd like to name you all by name, but the list

Has been removed and there is nowhere else to look.

So,

I have woven you this wide shroud out of the humble

words

I overheard you use. Everywhere, forever and always,

I will never forget one single thing. Even in new

grief.

Even if they clamp shut my tormented mouth

Through which one hundred million people scream;

That's how I wish them to remember me when I am dead

On the eve of my remembrance day.

If someone someday in this country

Decides to raise a memorial to me,

I give my consent to this festivity

But only on this condition - do not build it

By the sea where I was born,

I have severed my last ties with the sea;

Nor in the Tsar's Park by the hallowed stump

Where an inconsolable shadow looks for me;

Build it here where I stood for three hundred hours

And no-one slid open the bolt.

Listen, even in blissful death I fear

That I will forget the Black Marias,

Forget how hatefully the door slammed and an old woman

Howled like a wounded beast.

Let the thawing ice flow like tears

From my immovable bronze eyelids

And let the prison dove coo in the distance

While ships sail quietly along the river.

[March 1940. Fontannyi Dom]

FOOTNOTES

1 An elite guard which rose up in rebellion

against Peter the Great in 1698. Most were either

executed or exiled.

2 The imperial summer residence outside St

Petersburg where Ahmatova spent her early years.

3 A prison complex in central Leningrad near the

Finland Station, called The Crosses because of the

shape of two of the buildings.

4 The Leningrad house in which Ahmatova lived.

Submitted: Friday, January 03, 2003